Gluteal tendinopathy

Introduction

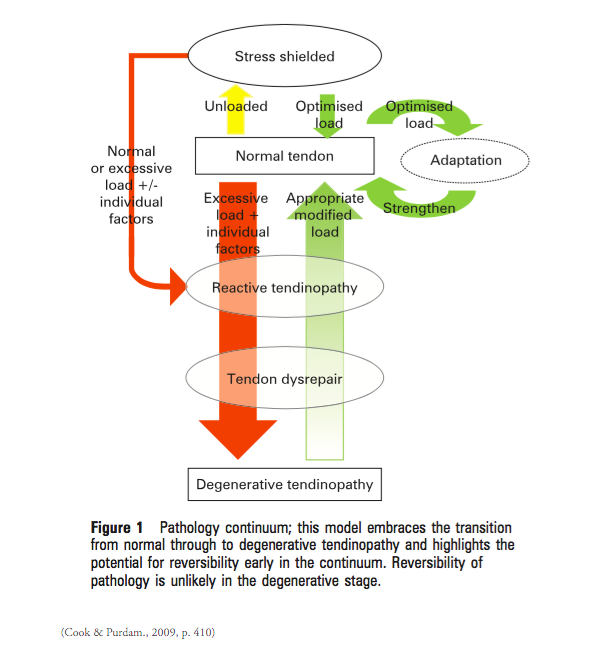

There was a surge of research around the pathophysiology of tendon pathology in 2009, with a notorious article being published by Cook & Purdam titled Is tendon pathology a continuum model? The findings of this article have been summarised in a previous blog, which discusses how Cook & Purdam have paved the way for changing our previous understanding of why tendons become pathological and how pain is driven in these conditions.

Since that time, the term tendinopathy has been more readily adopted into clinical practice and we more commonly see clinicians and patients accepting the idea that tendons don’t become inflamed. Instead, compression is thought to create the cell-induced tendinopathic process within the tissues (Cook & Purdam., 2012). As our body of knowledge has grown, researchers have also started to question if tendons behaviour differently based on their location and function in the body. Much research has been conducted around patella tendinopathy and achilles tendinopathy, yet, the research around gluteal tendinopathy remains less conclusive.

Lateral hip pain, which was more commonly referred to as trochanteric bursitis in the past, is now recognised to be more closely associated with gluteal tendinopathy than bursitis (Grimaldi & Fearson., 2015). Specifically, gluteus medius tendinopathy. As the term lateral hip pain has evolved from trochanteric bursitis, to greater trochanteric pain syndrome, to gluteal tendinopathy, we too have seen a growing amount of clinic trials published sharing what is known about this condition and evaluating the effectiveness of our current treatment methods.

I was thrilled to see a paper recently released in the BMJ by a powerhouse group of researchers on the effectiveness of three different treatment approaches for this condition. Mellor, Bennell, Grimaldi et al (2018) conducted the first RCT to evaluate the effect of: education about tendon loading & exercises specific to stage of tendon pathology, versus a single CSI, versus a wait and see approach, on pain and functional outcomes with gluteal tendinopathy. This was the first year that such an RCT has been published and by a renowned group of individuals who have been researching lateral hip pain/hip muscle function for many years.

What was already known on the topic:

- Corticosteroid injections are commonly used to treat tendinopathy, with good short term outcomes but poorer long term outcomes.

- Exercise is recommended for tendinopathies in general, but no randomised clinical trials have investigated its effects in gluteal tendinopathy.

RTC study design

The protocol for this trial was published in 2016 with the following key details:

Inclusion criteria (Mellor & Grimaldi., 2016, p.4):

- Lateral hip pain, worst over the greater trochanter, present for a minimum of 3 months.

- Age 35–70 years.

- Pain at an average intensity of ≥4 out of 10 on most days of the week.

- Tenderness on palpation of the greater trochanter.

- Reproduction of pain on at least one of five diagnostic clinical tests (FABER test, Static muscle contraction in FABER position, FADER test, Adduction test, Static muscle contraction in Adduction position, or single leg stance test).

- Demonstrated tendon pathology on MRI.

Exclusion criteria:

- To exclude other causes of hip pathology or referred pain mechanisms, patients are required to have ≥90 degrees hip and ≥90 knee flexion bilaterally, full knee extension bilaterally and a negative hip quadrant test.

- Participants also needed to be able to flex forward to the level of their knees with pain <2/10 on the VAS and squat to at least 60 degrees flexion at the hips.

- One of the key differentiating features between lateral hip pain and hip OA is the ability to lean forward and manipulate shoes and socks, which should not be affected by lateral hip pain but is often limited in hip OA (Fearson & Scarvell., 2013).

Outcome measures used in this trial included: the Global rating scale, VISA-G questionnaire, VAS, PSFS, MMT of hip abduction, Pain catastrophisation scale, and Self-efficacy scale.

Physical examination & diagnosis

MRI is an important aspect of diagnosis and is used in combination with a physical examination to confirm pathological changes within the tendon and the diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy.

Using a battery of clinical tests is important to improve the validity of clinical tests available to diagnose gluteal tendinopathy.

- Pain on direct palpation of the gluteal tendon insertion onto the greater trochanter

- Pain/positive test findings with at least one of the following:

- Passive FADER - places the gluteal tendons under compressive load

- FADER with static muscle IR at EOR (FADER-R) - at 90 degrees hip flexion, glut med and glut min produce hip IR which would therefore place the tendons in a further compressive state with the addition of a isometric muscle contraction.

- FABER - places gluteal tendons under tensile load

- Passive hip adduction in side lying - places the gluteal tendons under compressive load

- Resisted abduction from the adduction position (ADD-R) - this active abduction contraction from an adducted position places additional tensile load on the already compressed tendons.

- Single leg stance - the patient stands side-on to the wall with one finger on the wall for balance and attempts to stand on the outer leg for 30 seconds.

The tests listed above are considered to be provocative tests for reproducing symptoms of gluteal tendinopathy, i.e. even though some these are passive ROM, strength or balance, they are considered positive with reproduction of lateral hip pain (Mellor, et al., 2018, p.3). These clinical tests were previously investigated for their sensitivity and specificity (Grimaldi, Mellor, et al., 2017). What the authors found is that:

- Positive pain on palpation combined with at least of the pain provocation tests listed above significantly increases the likelihood of diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy on MRI. In fact, pain on palpation in combination with pain during the SLS test had the highest specificity (Grimaldi, Mellor, et al., 2017).

- The tests that incorporate a muscle contraction (SLS, FADER-R & Add-R) are more useful in diagnosis as they combine both tensile and compressive load to the tendon.

Treatment recommendations for exercise

The following treatment recommendations are drawn from this recently published RCT (Mellor, Bennel, Grimaldi, et al., 2018). Exercise and education is the current cornerstone treatment for non-surgical management of gluteal tendinopathy. More specifically for this condition, patient should be educated about avoiding compressive loading of the tendon, and provided with a gradually progressive strengthening program targeting this lateral hip abductor muscle synergy and based on research around tendon loading programs.

- Exercises in this trial were to be performed daily and consist of 4-6 exercises, taking 15-20 minutes to complete.

- Treatment frequency with the physiotherapist included once a week for the first 2 weeks, then twice a week for the remaining 6 weeks.

- Isometric tendon loading, muscle hypertrophy of the gluteal muscles and control of frontal-plane pelvic mechanics all need to be addressed concurrently in rehabilitation. These main areas have previously been identified in the optimal management of gluteal tendinopathy (Grimaldi & Fearson., 2015).

- For functional exercises, no change in pain levels was acceptable as this might indicate faulty position or biomechanics.

- For slow, heavy resistance training, a pain rating of 5/10 was acceptable as long as the pain eased after completing the exercise and did not result in pain later that night or the following day. (This is an important tool to teach patients how to monitor tendon loading.)

- The exercises recommended in this trial are clearly outlined in tables on page 7 & 8 (Mellor, et al., 2016).

Each week the program had a focus on:

- Low load activation = Static abduction

- Pelvic control in a functional position = bridges with varying levels of difficulty

- Functional strengthening = squats with varying levels of difficulty

- Abductor loading in frontal plane = side stepping, side splits on pilates reformer, side stepping with band

One thing to note is that not all gluteal exercises are equivalent in their ability to provide muscle hypertrophy while minimising compressive tendon loading. Here are some things to consider:

- Clams were not included - these are both a combination of movement through adduction and compression in side lying that would not be suitable for this condition.

- Weight bearing allows for better muscle hypertrophy and activation without compression.

Dosage is key!

- “Sustained isometric muscle contractions are now commonly employed clinically for management of tendon pain” (Grimaldi & Fearson., 2015, p. 918). Low-low (25% max voluntary contraction) is preferable to create analgesic effects in tendon pathology.

- Low-velocity and high tensile load are preferrable for muscle hypertrophy, while inner-range hip abduction positions minimise the compressive load on tendons (Grimaldi & Fearson., 2015, p. 919). These types of exercises should be performed 3 x week and night-pain is a indicator of over-loading the tendon.

- Each week there was a low load isometric exercise and for many of the other exercise, slowly load is preferred with 5-10 reps and 1 set, repeated 1-2 x day.

- If you require further information for isometric hip abduction strengthening in supine or standing, refer to the 2015 article.

Strength exercises shown to be helpful

Treatment recommendations on load management

Grimaldi & Fearson (2015) published a very detailed article discussing the importance of load management for gluteal tendinopathy. They discuss both positions of high compressive load as well and tips for reducing tendon load.

The gluteus medius and minimus tendons are susceptible to compressive loading through hip adduction movements at the region of the greater trochanter (Cook & Purdam., 2012). Therefore, piriformis and ITB stretching (which is still commonly recommended as a treatment) contradicts current research findings that compressive loads through excessive hip adduction contributes to the development of gluteal tendinopathy. These stretches are not recommended in treatment programs. Other ways to educate your patients about adduction/compression loading is not to sit with knees together or legs crossed (in hip adduction) and not to stand "hanging" out in hip adduction/pelvic tilting.

Postures shown to increase compressive load (not helpful)

(Grimaldi & Fearson., 2015, p.916

Stretches that increase compressive load (not helpful)

Summary of findings:

“Current evidence suggests that management of tendinopathy needs to be targeted to the tendon and in that regard: (a) the diagnosis should involve a combination of clinical examination and MRI confirmation of tendon involvement, (b) an injection should be guided by imaging so as to be specific and (c) any exercise be undertaken as part of a load management approach, which is now being recommended as the frontline treatment for managing tendinopathy.” (Mellor, Grimaldi, et al., 2016, p. 14).

“For gluteal tendinopathy, education plus exercise and corticosteroid injection use resulted in higher rates of patient reported global improvement and lower pain intensity than no treatment at eight weeks. Education plus exercise performed better than corticosteroid injection use. At 52 week follow-up, education plus exercise led to better global improvement than corticosteroid injection use, but no difference in pain intensity. These results support EDX (exercise and education) as an effective management approach for gluteal tendinopathy.” (Mellor, Bennell & Grimaldi., 2018, p.1).

Sian

References:

Cook, J., & Purdam, C. R. (2009). Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine, 43(6), 409-416.

Cook, J. L., & Purdam, C. (2012). Is compressive load a factor in the development of tendinopathy?. Br J Sports Med, 46(3), 163-168.

Fearon, A. M., Scarvell, J. M., Neeman, T., Cook, J. L., Cormick, W., & Smith, P. N. (2013). Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: defining the clinical syndrome. Br J Sports Med, 47(10), 649-653.

Grimaldi, A., & Fearon, A. (2015). Gluteal tendinopathy: integrating pathomechanics and clinical features in its management. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 45(11), 910-922.

Grimaldi, A., Mellor, R., Hodges, P., Bennell, K., Wajswelner, H., & Vicenzino, B. (2015). Gluteal tendinopathy: a review of mechanisms, assessment and management. Sports Medicine, 45(8), 1107-1119.

Grimaldi, A., Mellor, R., Nicolson, P., Hodges, P., Bennell, K., & Vicenzino, B. (2017). Utility of clinical tests to diagnose MRI-confirmed gluteal tendinopathy in patients presenting with lateral hip pain. Br J Sports Med, 51(6), 519-524.

Mellor, R., Grimaldi, A., Wajswelner, H., Hodges, P., Abbott, J. H., Bennell, K., & Vicenzino, B. (2016). Exercise and load modification versus corticosteroid injection versus ‘wait and see’for persistent gluteus medius/minimus tendinopathy (the LEAP trial): a protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 17(1), 196.

Mellor, R., Bennell, K., Grimaldi, A., Nicolson, P., Kasza, J., Hodges, P., ... & Vicenzino, B. (2018). Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. bmj, 361, k1662.