Surgical vs non-surgical treatment for the knee

Image courtesy of Google Images

Presented in this blog are the key messages from CPG over the past 10 years regarding the assessment and treatment (both surgical and non surgical) for meniscal lesions, degenerative knee disease, articular cartilage lesions, and ACL tears.

The inspiration for this blog comes from a recent paper published in BMJ in 2018 updating the

clinical practice guidelines for arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears. This review is based on recommendations from two systematic reviews and an expert panel.

In short, these recommendations strongly discourage knee surgery and strongly support conservative treatment for these conditions. You can access the journal here. “Patients and their healthcare providers must trade-off the marginal short-term benefits against the burden of the surgical procedure (pain, swelling, limited mobility, restriction of activities) over a period of 2-6 weeks” when making decisions regarding the role of arthroscopy for degenerative knee disease (Brignardello-Petersen, et al., 2017, p. 10).

When reading through the article I realised that quickly I was interpreting these recommendations for all cases on knee pain and not specifically DKD and meniscal tears. This has then prompted me to review the most recent CPGs for knee ligament sprains, articular cartilage tears and other common knee injuries, to understand the current recommendations for surgical versus non-surgical care.

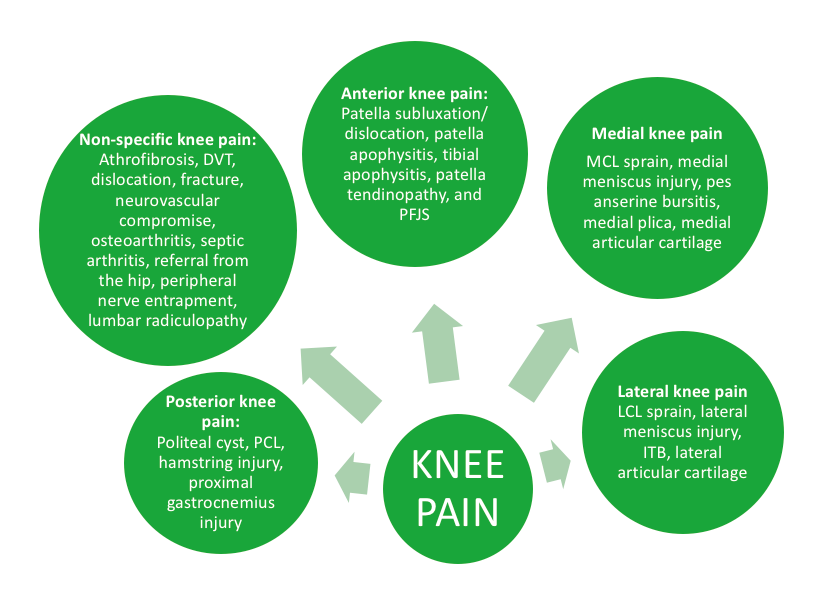

Differential diagnosis of knee pain

Before we look at the different conditions, let's recap the conditions up for consideration with differential diagnosis.

Adapted from information presented in paper by Logerstedt et al (2010, p.A11)

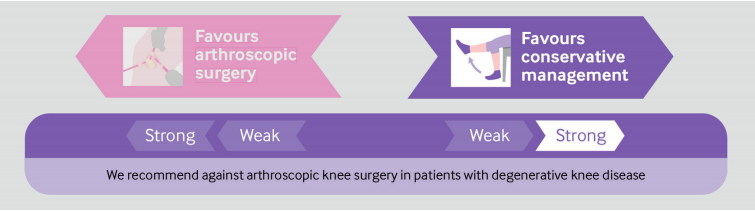

Siemieniuk et al., 2018, p. 1

Degenerative knee disease

For degenerative knee disease, arthroscopy is not recommended as it does not provide a better recovery, has a greater impact on QOL initially and is a huge financial burden to the government.

- “~25% of people >50 years of age experience knee pain from degenerative knee disease” (Siemieniuk, et al., 2018, p. 1).

- “Arthroscopic procedures for degenerative knee disease cost more than $3billion per year in the US alone” (Siemieniuk, et al., 2018, p. 3).

Degenerative knee disease is an inclusive term, which many consider synonymous with osteoarthritis. We use the term degenerative knee disease to explicitly include patients with knee pain, >35 y.o, with/without the following (Siemieniuk, et al., 2018, p. 3):

- Imaging evidence of OA

- Meniscal tears

- Locking, clicking, or other mechanical symptoms except persistent objective locked knee

- Acute/subacute onset of symptoms.

This term, degenerative knee disease (DKD) does not include patients with symptoms that began after trauma or acute onset of knee swelling.

In 2017, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care published the clinical standard guidelines for management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Some key statements from these guidelines (pages 4-20):

- People with knee osteoarthritis typically present with pain, with or without stiffness and swelling around the joint.

- They often have difficulty with walking, climbing stairs, standing from a sitting position, getting in and out of cars and other everyday activities.

- Such physical limitations often hinder a person’s participation in work, leisure and social activities, and can contribute to psychological distress, including depression.

- Osteoarthritis is not an inevitable part of ageing and is not necessarily progressive.

- Symptoms can be managed and the level of physical activity improved by modifying risk factors such as excessive weight.

- Being overweight doubles a person’s risk of developing knee osteoarthritis, while obesity increases the risk more than fourfold.

- Losing a moderate amount of weight can improve symptoms and the physical capability of people with knee osteoarthritis.

- Arthroscopic procedures are not effective for treating knee osteoarthritis.

ACL reconstructions

In the CPG from 2009 from Beaufils et al on meniscal lesions and ACL injuries, there was a large emphasis on meniscal preservation with ACL reconstruction. The authors offer a CPG that provides a clear pathway for guiding clinical reasoning on how to determine the need for referral to surgery.

“Meniscal preservation is the rule” in ACL deficient knees (Beaufils, et al., 2009, p.439).

The key messages from this paper were (Beaufils, et al., 2009, p.437-440):

- Meniscal repairs should only be used to heal peripheral meniscal lesions affecting healthy meniscal tissue in vascularised areas. Repair of unvascularised zones is not recommended.

- Traumatic lesions do not always require meniscectomy.

- Management of cartilage damage is dependent on the extent of the damage.

- ACL reconstructions should be considered based on symptoms and functional instability.

- Arthroscope is the only technique for surgical repair of meniscal lesions and the preferred technique for chronic ligament lesions.

- It is not possible to favour one rehab protocol over another.

- MRI should be performed for traumatic meniscal lesions to specify the type of lesion, the state of the ACL and to look for bone contusion.

“Meniscal repair gives satisfactory medium-term clinical results in 70-90% of patients, provided that it concerns the peripheral red-red zone or red-white zone lesions, i.e. peripheral vascularised area” (Beaufils, et al., 2009, p.439).

Meniscectomy without ligament reconstruction (in an ACL deficient knee) should be proposed only if all 4 following criteria are met (Beaufils, et al., 2009, p.440):

- Symptomatic meniscal lesion

- Irreparable meniscal lesion

- No functional instability

- Inactive/elderly patient

Indication for ACL reconstruction (Beaufils, et al., 2009, p.440-441):

- Early surgery is not mandatory! You want to reduce the complications of stiffness and DVT therefore it is often recommended to wait initially.

- Early surgery is most commonly considered if there is a bucket handle tear or osteochondral lesion.

- Decisions about surgery are often made from the assessment of functional impairment.

- Delayed end feel on lachman’s is a sign of a partial tear.

- Gross instability on a pivot shift test.

- The demands of the patient’s sport/occupation.

- Peripheral meniscal lesion.

In the 2010 CPG (Logerstedt, et al., 2010) there is a discussion about the ACL coper versus non-coper. A patient is considered a coper if they are a L1 or L2 athlete, have no concomitant injuries, have no effusion, have full knee ROM and normal gait, have >70% isometric quadricep strength compared to the non-injured side and can hop on the injured leg without pain (Logerstedt, et al., 2010, p.A12). If the patient meets these criteria they can then go through the Fitzgerald screening exam developed in 2000 which is a helpful decision making tool for identifying copers. The downfall is that this tool does not have good sensitivity (44%) for correctly identifying copers long term (at 1 year).

This screening tool can still be used to help identify ACL deficient copers if you need guidance in your clinical exam. Ultimately, the specialists are normally responsible for suggesting surgical repair of the ACL.

- No episodes of giving way (need to have <1 episode)

- Maximum voluntary quadricep contraction and single leg hop test x 4 need to be 80% of the contralateral side

- KOS-ADLS score >80%

- Global rating scale >60%

Meniscal lesions & Articular cartilage lesions

In 2018 a revised CPG for meniscal and articular cartilage lesions was published (Beattie, et al., 2018).

- “Injuries to the menisci are the second most common injury to the knee, with a prevalence of 12-14% and an incidence of 61 cases per 100 000 persons.” (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A7).

- “In the united states alone, 10-20% of all orthopedic surgeries consist of surgery to the meniscus” (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A7).

- Therefore, it is very important that as therapists we are choosing the best patient’s to have this procedure.

- “32-58% of all articular cartilage lesions are a result of a traumatic, non contact mechanism of injury” (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A7).

Diagnosis of a meniscal lesion can be made with fair certainty with the following features (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A15).:

- Twisting mechanism of injury

- Catching or locking

- Delayed effusion (6-24 hours)

- Meniscal pathology composite score >⅗

- Catching/locking

- Pain with forced hyperextension

- Pain with maximum passive knee flexion

- Joint line tenderness

- Audible click on McMurray’s maneuver.

McMurray’s in isolation as a test has a sensitivity of 55% and specificity of 77% and therefore needs to be completed in combination with the other physical tests listed above.

Diagnosis of an articular cartilage lesion can be made with less certainty with the following features (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A15):

- Acute trauma with haemarthrosis

- Insidious onset associated with repetitive impact

- Intermittent pain and swelling

- History of locking and catching

- Joint line tenderness

“Four methods of operative care that are most widely used are arthroscopic lavage and debridement, microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) and osteochondral autograft transplantation (OAI)” (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A9).

Physiotherapy assessment & Intervention

Physiotherapy assessment should include the following three regions.

- Outcome measures for activity limitations: SF-36, European QOL (EQ-5D), IKDC and the KQol-26 were all recommended.

- Physical performance tests: SL hop for distance, triple hop for distance, crossover hop test, 6m hop for time, TUGT, 6MWT, stair climb (9 stairs) were all recommended.

- Physical impairment tests: pain at rest and with movement, pain behaviour over 24 hours, aggravating movements, modified stroke assessment, knee AROM in flexion and extension, voluntary isometric quadricep strength, pain with forced hyperextension, pain with maximal passive knee flexion, McMurray’s test and palpation of the joint line.

** Each of these tests (and previously recommended others) are all described in details in the 2010 CPG. The tests have a description, outline of purpose and psychometric properties.

** MRI should be reserved for complicated or confusing cases to assist specialists with planning for surgery and patient prognosis (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A19).

Intervention recommendations:

- Progressive ROM (both active and passive) is a first point of treatment

- Progressive weight bearing is often involved in the first 6-8 weeks

- Return to activity based on the type of surgery (meniscal repair, articular cartilage repair, ACL reconstruction)

- Strength of knee and hip muscles is crucial in knee rehabilitation

- Neuromuscular training is critical for return of function

- ESTIMS for neuromuscular training can be used as required

Ottowa knee rules (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A19):

- Sensitivity of 99 and specificity of 49

- Knee XRAY is required when

- >55 years of age

- Tenderness isolated to palpation of the patella

- Tenderness over the head of the fibula

- Unable to flex the knee > 90 degrees

- Unable to weight bear immediately or in ED 4 steps regardless of limping.

Take home message:

- There are several validated measures for quality of life, impact of disability, physical performance and physical impairments.

- These are described in detail in the two 2010 CPG listed in the references

- These tests are commonly used across all conditions discussed in this blog to assist with clinical decision making to guide rehab speed and to decide on the suitability for surgical intervention

- Knee injury diagnosis relies heavily on the clinician recognising a cluster of symptoms which are commonly associated with each condition.

- The primary aim of assessment is to determine if physical therapy is appropriate and what the main physical impairments are associated with the injury/condition (Beattie, et al., 2018, p.A16).

- The general lack of discussion about details of treatment is reflected by the need of the therapist to first identify major physical impairments rather than prescribing protocols for diagnostic labels. Treat what you find!

- Every article did emphasise that knee extensor strength was very important to recovery and long term outcomes.

We are living in a knowledge-hungry era, where patients are motivated to learn as much as they can about their individual problems. As health care providers, it is our responsibility to educate them about their condition. If we fail to achieve this task of education and clear communication, patients more than often searching for answers online. As we all know, this can open a CAN OF WORMS and create even more work in challenging faulty beliefs and breaking down misunderstood information. Hopefully this update consolidates your current knowledge base on the clinical reasoning that leads to decisions regarding surgical and non-surgical management and gives you the confidence to educate patients about the benefits and risks of both approaches.

Sian

References:

Beaufils, P., Hulet, C., Dhenain, M., Nizard, R., Nourissat, G., & Pujol, N. (2009). Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, 95(6), 437-442.

Brignardello-Petersen, R., Guyatt, G. H., Buchbinder, R., Poolman, R. W., Schandelmaier, S., Chang, Y., ... & Vandvik, P. O. (2017). Knee arthroscopy versus conservative management in patients with degenerative knee disease: a systematic review. BMJ open, 7(5), e016114.

Chou, L., Ellis, L., Papandony, M., Seneviwickrama, K. M. D., Cicuttini, F. M., Sullivan, K., ... & Wluka, A. E. (2018). Patients’ perceived needs of osteoarthritis health information: A systematic scoping review. PloS one, 13(4), e0195489.

Li, L. C., Sayre, E. C., Xie, H., Falck, R. S., Best, J. R., Liu-Ambrose, T., ... & Feehan, L. M. (2018). Efficacy of a Community-Based Technology-Enabled Physical Activity Counseling Program for People With Knee Osteoarthritis: Proof-of-Concept Study. Journal of medical Internet research, 20(4), e159.

Lo, G. H., Musa, S. M., Driban, J. B., Kriska, A. M., McAlindon, T. E., Souza, R. B., ... & Jackson, R. D. (2018). Running does not increase symptoms or structural progression in people with knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Clinical rheumatology, 1-8.

Logerstedt, D. S., Snyder-Mackler, L., Ritter, R. C., Axe, M. J., & Godges, J. J. (2010). Knee stability and movement coordination impairments: knee ligament sprain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(4), A1-A37.

Logerstedt, D. S., Scalzitti, D. A., Bennell, K. L., Hinman, R. S., Silvers-Granelli, H., Ebert, J., ... & McDonough, C. M. (2018). Knee Pain and Mobility Impairments: Meniscal and Articular Cartilage Lesions Revision 2018: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 48(2), A1-A50.

Logerstedt, D. S., Snyder-Mackler, L., Ritter, R. C., Axe, M. J., & Godges, J. J. (2010). Knee stability and movement coordination impairments: knee ligament sprain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 40(4), A1-A37.

Siemieniuk, R. A., Harris, I. A., Agoritsas, T., Poolman, R. W., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Van de Velde, S., ... & Helsingen, L. (2017). Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee arthritis and meniscal tears: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ, 357, j1982.

Thorlund, J. B., Juhl, C. B., Ingelsrud, L. H., & Skou, S. T. (2018). Risk factors, diagnosis and non-surgical treatment for meniscal tears: evidence and recommendations: a statement paper commissioned by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF). Br J Sports Med, 52(9), 557-565.

Wylde, V., Dennis, J., Gooberman-Hill, R., & Beswick, A. D. (2018). Effectiveness of postdischarge interventions for reducing the severity of chronic pain after total knee replacement: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ open, 8(2), e020368.