Suprascapular nerve palsy

Image courtesy of Google images

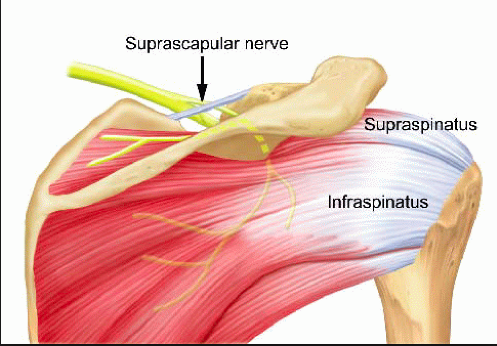

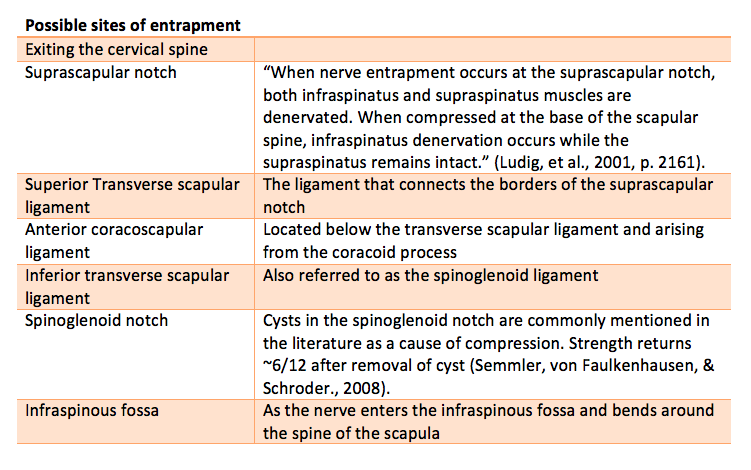

“Suprascapular nerve entrapment syndrome (SNES) is a neuropathy in which the nerve is compressed along its course, most commonly at the suprascapular notch (SSN)” (Łabętowicz, et al., 2017, p. 1). It was first described by Kopell and Thomas in 1959, as a condition characterised by weakness in abduction and external rotation and ill-defined pain (Kopell & Thompson., 1959). The suprascapular nerve provides motor innervation to supraspinatus and infraspinatus, and articular innervation to the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints. PARESIS is the primary concern, therefore, upper limb neurological examination will reveal normal deep tendon reflexes and sensation.

How does it typically present?

- Weakness in abduction and external rotation in ~84% of cases (Momaya, et al., 2018, p. 174).

- Visible atrophy of the either both supraspinatus and infraspinatus, or just infraspinatus (depending on the location of the entrapment) in approximately 78% of cases (Momaya, et al., 2018, p. 174).

- Non-specific shoulder pain (Fritz, et al., 1992, p. 441).

- 97.8% of cases present with deep posterior shoulder pain (Momaya, et al., 2018, p. 174).

How common is it?

It is a fairly rare condition. I’ve seen it three times in my career. Once in an overhead athlete, once with a patient who had radiation therapy for thyroid cancer, and once with a patient with leukemia that developed symptoms following a vaccination into the left shoulder.

Many of the articles I found online date back to 1976 and the amount of literature is limited. Some articles suggest that it is the cause of about 1-2% of conditions presenting as shoulder pain and dysfunction (Łabętowicz, et al., 2017) and a more recent systematic review found that 58.6% of presentations occur from repetitive overhead activities, 31% from occupational activities and 10% from an unknown mechanism (Momaya, et al., 2018). In the overhead athlete, it is more commonly present in the dominant arm and thought to be related to repetitive abduction and full rotation (Holzgraefe, Kukowski & Eggert., 1994), as this would stress the infraspinatus branch of the suprascapular nerve (Łabętowicz, et al., 2017).

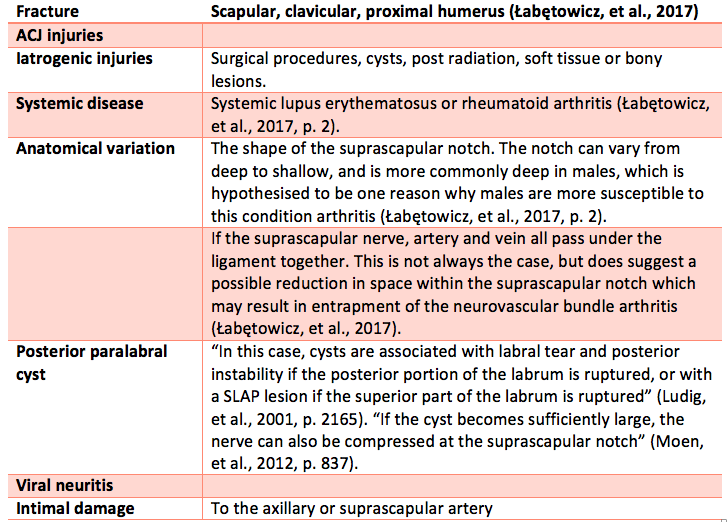

Other causes may include:

Clinical anatomy of the suprascapular nerve

Image courtesy of Google Images and wikipedia

What is the course of the suprascapular nerve?

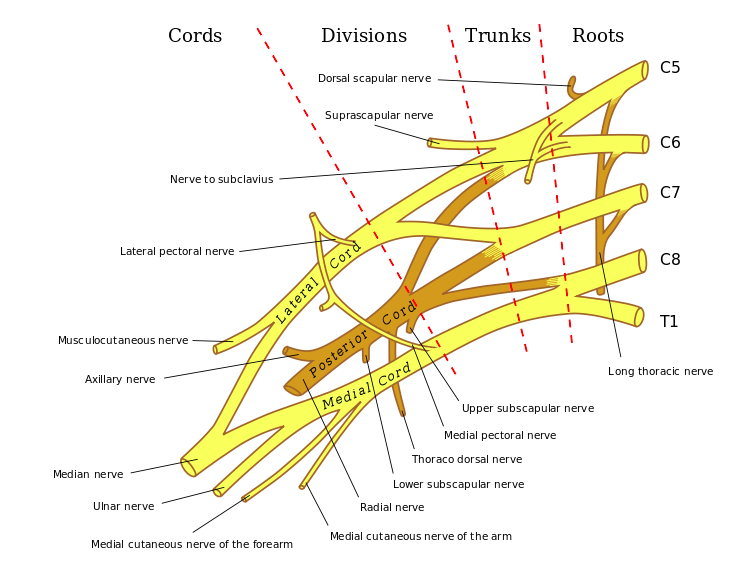

- The suprascapular nerve specifically, arises from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus, before the medial, lateral and posterior cords are formed. It is mostly comprised of nerve roots from C5 & C6. After leaving the brachial plexus, the suprascapular nerve passes under the trapezius and omohyoid muscles (Drez, 1974).

- “After departing the brachial plexus, the suprascapular nerve courses laterally through the posterior cervical triangle, posterior to the clavicle, then across the superior border of the scapular and into the suprascapular notch” (Moen, et al., 2012, p. 835-836).

- It then travels under the suprascapular notch and superior transverse ligament. Here it gives off a branch to the supraspinatus muscle and articular branches to the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints ((Holzgraefe, Kukowski & Eggert., 1994).

- The nerve then continues along the lateral scapula to the spinoglenoid notch, passes under the inferior transverse ligament and enters the infraspinous fossa to innervate the infraspinatus muscle (Holzgraefe, Kukowski & Eggert., 1994).

Differential diagnoses to consider (Moen, et al., 2012):

- Rotator cuff tendinopathy or tear. “Large retracted rotator cuff tears are also being increasingly recognized as causing suprascapular nerve injury.” (Moen, et al., 2012, p. 837). As the tear retracts it can alter the pathway of the nerve.

- Glenhumeral joint dislocation or instability

- Brachial plexus injury

- Cervical disc disease or radiculopathy

Patient prognosis & rehabilitation

The role of physical therapy.

“The goal of strengthening is to enhance the compensatory muscles and to regain muscular balance about the shoulder. Using proper posture, including scapular retraction exercises, and participating in proprioceptive exercises may be beneficial. Most authors recommend at least 4 to 6 months of nonoperative management with follow-up electrodiagnostic testing to determine whether recovery is progressing.” (Safran., 2004, p. 810).

There are two main focusses of our physiotherapy program; regain external rotation strength and muscle hypertrophy, and, protect the shoulder joint from overload due to faulty compensations.

STRENGTHENING EXTERNAL ROTATION

The following sequence is what I have found to be clinically helpful. The length of time in each phase of training is dependent on the cause of the neuropathy and patient progress.

- Alternating isometrics in sitting using a dowel

- Isometric ER on the affected arm which moving the unaffected arm through rotation with a theraband. This provides a fluctuating resistance on an isometric hold.

- Progressive external rotation strengthening once active range of movement has been regained

OPTIMISING PERISCAPULAR MUSCLE CONTROL AND POSTURE

After an external rotation strengthening program has been established, I try to being exercises to promote postural awareness and control of the glenohumeral joint and scapula. One of the issues patients face is a lack of awareness of positioning of the humeral head at rest and during movement. Of the cases I've seen, patients present with a forwardly positioned and anteriorly rotated humeral head.

The exercise above used a theraband to provide proprioceptive feedback to the back of the shoulder, while the patient actively moves the arm in and out of flexion at waist height. Once this posture has been learnt, the patient can progressed to a bent over tricep row.

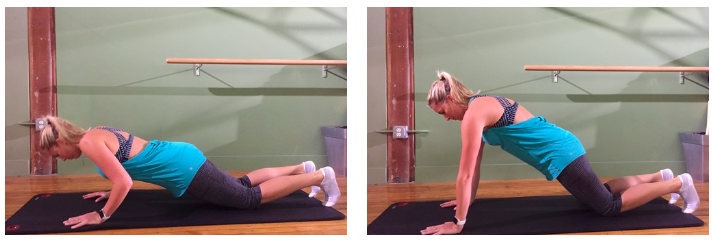

A second common functional issue is pain with shoulder elevation, either in abduction or flexion. To investigate a patient's scapular control during flexion I commonly chose to use weight bearing, as this often reveals scapula winging or changes in postural control between left and right sides.

The first step was to teach the patient how to plank either in quadruped or a forward kneeling position. Once they are able to position their scapula (by pressing away from the floor and bringing ribs to meet scapula), they was able to actively move through a kneeling push up. As their strength progresses the patient may be able to progress to a full plank and full push up position without aggravating their shoulder.

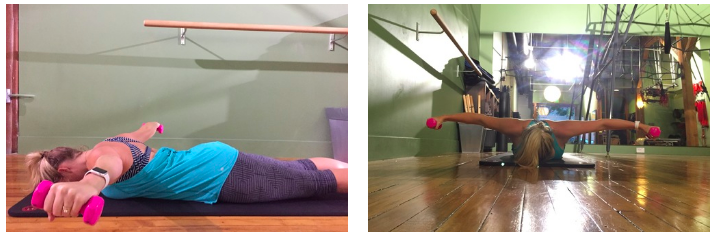

Later in rehabilitation, as the patient strengthens their abduction and external rotation above 90 degrees, you may choose to use this prone abduction exercise.

Is further investigation required?

“The current literature shows that the location and mechanism of nerve injury are the most important factors guiding management” (Moen, et al., 2012, p. 844). Therefore, it is very important to try decipher the cause of injury.

Often however, it a diagnosis of exclusion of other causes of shoulder weakness and pain, which can mean there is a prolonged period of time between examination, diagnosis and treatment to relieve nerve entrapment. Momaya et al (2018) found that this time frame on average is 19 months and that the diagnosis is often only confirmed following an EMG study.

“EMG is the gold standard and is essential to confirm muscle denervation; however, it is seldom carried out initially because clinical data rarely point to the diagnosis of neuropathy” (Ludig, et al., 2001, p.2162).

MRI can be used to evaluate muscular edema, muscle atrophy, fatty changes within the muscle and look for the presence of cysts within the tissues (Ludig, et al., 2001). In this study the authors felt that the presence of muscular edema was a more significant sign of neuropathy on MRI than muscular atrophy or fatty changes. It should be mentioned that muscle edema can be the result of many different conditions, however when using MRI to diagnose a neuropathy, the authors found this sign to be the most significant. “Muscular edema may be explained by hydration modifications of the muscular mass, in the case if denervated muscles” (Ludig, et al., 2001, p.2167).

The role of surgery.

The first systematic review of this condition was published in 2018 by Momaya and colleagues with the primary objective to report on clinical outcomes following suprascapular nerve decompression at the suprascapular notch or spinoglenoid notch. They found that following surgery, 100% of athletes who had decompression at the suprascapular notch and 91% of athletes who had decompression at the spinoglenoid notch were able to return to sport (Momaya, et al., 2018, p. 174).

“If after 6-8 weeks (in the cases presented) no evidence of regeneration was noted, surgical exploration of the nerve was then recommended” (Drez, 1974, p. 45). Currently, there are no studies that compare operative and nonoperative treatment for this condition ((Momaya, et al., 2018).

Take home messages

- Make the pieces fit! The difficulty with this condition lies in the diagnosis!

- Sometimes we need to think about the nerve or blood supply to a muscle/joint, not just the local structure thought to be causing the pain.

- Correlate your physical examination with patient history and medical imaging. Sometimes further examination is required to explain the patient presentation. Only EMG can confirm the diagnosis of suprascapular neuropathy (Drez, 1976).

- Always seek to exclude red flags and sinister pathology.

SS

References:

Antoniou, J., Tae, S. K., Williams, G. R., Bird, S., Ramsey, M. L., & Iannotti, J. P. (2001). Suprascapular Neuropathy: Variability in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 386, 131-138.

Drez JR, D. (1976). Suprascapular neuropathy in the differential diagnosis of rotator cuff injuries. The American journal of sports medicine, 4(2), 43-45.

Fritz, R. C., Helms, C. A., Steinbach, L. S., & Genant, H. K. (1992). Suprascapular nerve entrapment: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology, 182(2), 437-444.

Holzgraefe, M., Kukowski, B., & Eggert, S. (1994). Prevalence of latent and manifest suprascapular neuropathy in high-performance volleyball players. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(3), 177-179.

Kopell HP, Thompson WAL. Pain and the frozen shoulder. Surg Gynec Obst 1959; 109: 92-6.

Łabętowicz, P., Synder, M., Wojciechowski, M., Orczyk, K., Jezierski, H., Topol, M., & Polguj, M. (2017). Protective and Predisposing Morphological Factors in Suprascapular Nerve Entrapment Syndrome: A Fundamental Review Based on Recent Observations. BioMed research international, 2017.

Ludig, T., Walter, F., Chapuis, D., Molé, D., Roland, J., & Blum, A. (2001). MR imaging evaluation of suprascapular nerve entrapment. European radiology, 11(11), 2161-2169.

Moen, T. C., Babatunde, O. M., Hsu, S. H., Ahmad, C. S., & Levine, W. N. (2012). Suprascapular neuropathy: what does the literature show?. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 21(6), 835-846.

Momaya, A. M., Kwapisz, A., Choate, W. S., Kissenberth, M. J., Tolan, S. J., Lonergan, K. T., ... & Tokish, J. M. (2018). Clinical outcomes of suprascapular nerve decompression: a systematic review. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery, 27(1), 172-180.

Rengachary, S. S., Burr, D., Lucas, S., Hassanein, K. M., Mohn, M. P., & Matzke, H. (1979). Suprascapular entrapment neuropathy: A clinical, anatomical, and comparative study: Part 2: Anatomical study. Neurosurgery, 5(4), 447-451.

Safran, M. R. (2004). Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, part 1: suprascapular nerve and axillary nerve. The American journal of sports medicine, 32(3), 803-819.

Safran, M. R. (2004). Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, part 2: long thoracic nerve, spinal accessory nerve, burners/stingers, thoracic outlet syndrome. The American journal of sports medicine, 32(4), 1063-1076.