Pelvic girdle pain - treatment options during pregnancy

This is the third blog in a series exploring the most recently published clinical practice guideline for pelvic girdle pain in the antepartum population. The first two explored pathophysiology, clinical presentation and assessment, and this week we look at the recommendations for treatment of this condition.

The evidence supporting the effectiveness of physical therapy in the treatment of PGP in both the antepartum and postpartum population has been of great debate for many years. Most of the articles I have read track back to 2000, which correlates with boom in research published around the role of specific muscle stabilization in both LBP and PGP. Since that time many articles and RCT have been published exploring different approaches. I was eager to read the latest summary in this 2018 CPG, however it appears that there remains low level evidence to support the role of supportive devices, exercise and manual therapy as treatments for this patient population. Supportive devices and exercise were rated level D in regards to strength of evidence and manual therapy level C. Neither of these ratings provide the therapist with great confidence in the credibility of our EBP, yet here we are continuing to be the professionals treating and helping these women.

So digging a little deeper into the articles published over the past 18-20 years, here is a summary of the findings I felt were helpful in guiding clinical decision making. And I strongly advocate for women to seek advice and treatment from physiotherapists for this condition. Because, although we don’t have solid evidence backing our treatments, I believe that more than often we are effective in reducing pain and levels of disability, we teach women about safe ergonomics, and we empower them with the knowledge we do have to care for their new bodies as mothers.

Support belts & braces (Level D Evidence)

Summary of recommendations (from the 2008 & 2018 CPGs):

- “Clinicians should consider the application of a support belt in the antepartum population with PGP” (Clinton, et al., 2018, p.116).

- “A pelvic belt may be fitted to test for symptomatic relief, but should only be applied for short periods.” (Vleeming et al., 2008, p.810)

Mens et al (2006) investigated the impact of belt positioning on SIJ laxity and found it to be found effective when worn at a low level (over the pubic symphysis) or high level (over the ASIS). They speculated that when in a low position the belt might mimic the action of the pelvic floor muscles and when in a high position, the action of the transversus abdominus and multifidus. Whether or not this can be proved beyond theory is up for debate, so, the main focus is therefore to see if immediate symptomatic relief is achieved or not. In this particular study, the authors tested the impact of the belt during the ASLR test, which can be easily completed in the clinical setting to assess for ‘symptomatic relief’. Something to bear in mind is that this study included women with postpartum PGP that developed their symptoms during pregnancy.

None of the studies I read provided specific detail about which product is more effective, the application or duration of wear. My clinical experience is that for the belt to be effective, it must provide immediate relief with ASLR and walking, worn when in an upright position and not worn 24 hours a day.

Here are some belts I found online that can be used for SIJ pain in the antepartum and postpartum population. To my knowledge, none of these are superior products and it comes down to personal preference, comfort and effectiveness in pain reduction.

Other support garments I have found useful for PGP in the antepartum population are:

- SRC pregnancy shorts

- Coccyx donut cushion - for position of rest, not for upright support

Exercise (Level D evidence)

Summary of recommendations:

- “Clinicians should consider the use of exercise in the antepartum population with PGP. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) have recommended exercise for health benefits because of the low risk and minimal adverse effects for the antepartum population.” (Clinton, et al., 2018, p.119).

In general, exercise is recommended and supported during pregnancy. A great review published in 2012 by Nascimento et al., captures the following points.

- Pregnancy represents a special state in which women are often highly motivated to implement behavioural changes.

- Starting exercises during pregnancy could change the lifestyle of the woman with long-term positive impact.

- Exercise is safe for mother and foetus and should be indicated to all pregnant women in the absence of absolute contraindications.

- Exercise practice during pregnancy is associated with the control of gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, prevention of urinary incontinence and low back pain.

- All pregnant women should be encouraged to participate in aerobic and strength training at moderate-intensity sessions at least three times a week for 30 min or more.

- For pregnant women with chronic diseases (such as hypertension), more studies should be performed to certify the safety of the intervention.

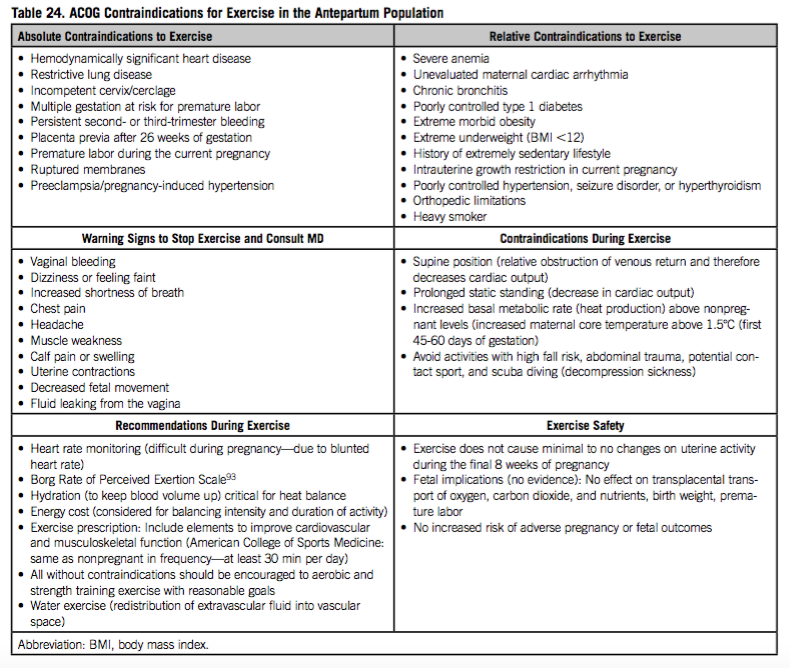

Contraindications to exercise during pregnancy (Clinton, et al., 2018)

Contraindications to exercise (from Clinton, et al., 2017, p. 122)

While exercise is a critical component of rehabilitation of PGP, there is limited evidence on which exercises have been shown to have the most efficacy. It is widely accepted that the muscles thought to be involved in producing force closure around the SIJ are TrA, obliques, lats and glute max (Stuge, Holm & Vøllestad., 2006). This theory of force closure around the SIJ has been well adopted in our profession and many of the trials evaluating the effect of stabilization exercises provide exercises each author believes is responsible in promoting this dynamic form of joint stability. Although the exercises vary from trial to trial, the muscles being targeted remain the same.

I have often used the ASLR test with different muscular biases to assess which muscle group provides the greatest relief. The ASLR test remains an important assessment tool for identification of altered motor control strategies and also can be used to monitor and predict recovery. “The delayed onset of obliquus internus abdominis, multifidus, and gluteus maximus electromyographic activity of the supporting leg during hip flexion, in subjects with sacroiliac joint pain, suggests an alteration in the strategy for lumbopelvic stabilization that may disrupt load transference through the pelvis” (Hungerford, Gilleard & Hodges., 2003, p.1593).

None of the articles I read from the 2018 CPG based their exercise prescription on the type/classification of PGP, which makes them difficult to apply directly to clinical practice.

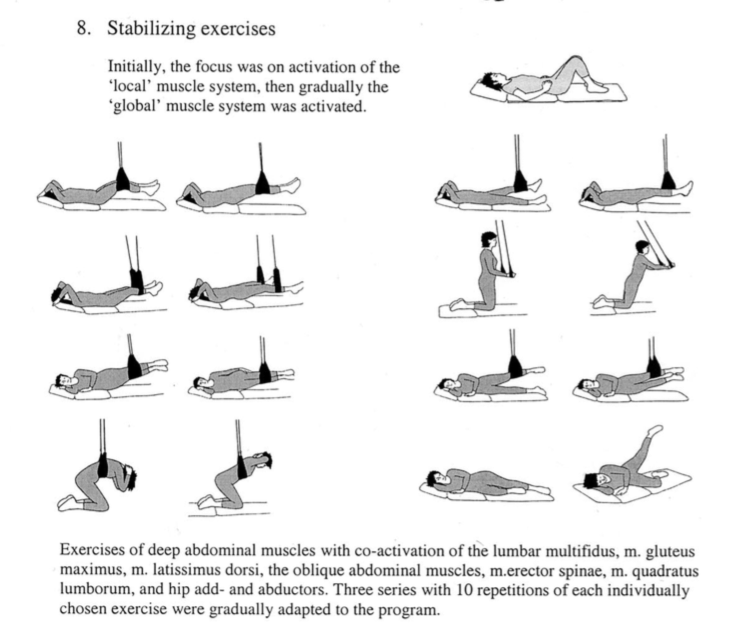

Stuge, Lærum et al (2004) conducted a RCT to explore the effect of specific stabilization exercise of PGP in the postpartum population. In this study patients completed 30-60 minutes of exercise, 3 x week for 18-20 weeks. Each exercise was aimed to be completed 10 times for 3 sets within each exercise session. That is nearly 5 months of continual strengthening! Being able to perform the exercises without aggravation of PGP was an important factor in compliance within this specific study. “After treatment, the specific exercise group showed clinically and statistically significant lower pain intensity, lower disability, higher quality of life, and better improvements on physical tests, compared with the control group.” (Stuge et al., 2004, p.358).

This leads me to ask 3 important questions:

- How many of our patients commit to a treatment time frame of that length?

- How do you educate your patients about monitoring pain production during exercise?

- Which of these exercises can safely be completed during pregnancy?

(Stuge, Lærum et al., 2004, p. 353)

The exercises above look applicable to postpartum recovery but how can this be applied to a pregnant mumma? Below are the exercises that I have used in the antepartum population to help target and strengthen these muscle groups. A key focus of each exercise is to perform the movement without aggravation of pain. Regardless of how 'difficult' the patient perceives the exercise to be, for me, it is important they are pain free. These exercises are by no means an absolute but more so a sharing of my ideas and experience treating this condition.

An important point to remember about exercise is that if we choose to begin patients with specific stabilisation exercises, we must continue to treat/educate patients until they are ready to progress into more dynamic and functional movements. Unfortunately, it is a far too common story that people become over-stabilised and rigid from remaining in this exercise philosophy for too long. Patients will also need to be taught how to move and retraining their painful movement patterns. It just doesn't make sense to use a high load static stabilisation exercise to retrain a low load postural position, and patients need to develop the knowledge of how to move well, how to position well and when exercises need to change/progress.

Manual therapy (level C evidence)

Summary of recommendations:

- "Clinicians may or may not utilize manual therapy techniques including high-velocity, low-amplitude manipulations for the treatment of PBLP and PGP. This evidence is emerging and treatment could be considered, as there is little to no reported evidence of adverse effects in the healthy antepartum population.” (Clinton et al., 2018, p.123)

Sadly there were not a lot of articles on manual therapy that provided specific detail to guide treatment. Personally, I find that thoracic mobilisation and soft tissue massage through the gluteals offload regions of the pelvic girdle and improve functional movements such as getting out of bed and sit to stand. I do not use pelvic manipulation or pubic symphysis manipulation with these patients. But that is completely my personal preference. Most often, I find that manual therapy is used as a pain-relieving tool to assist patients with performing their strengthening exercises more comfortably.

Recovery from PGP

Unfortunately we can’t view PGP as a normal part of pregnancy, despite the incredibly high prevalence. As practitioners, we shoulder encourage patients to seek treatment and advice for self management during and after the birth. For some mothers, symptoms may resolve after the birth, but that is not the case for all. Aiming to identify those at risk of developing long term pain is helpful for putting in place strategies for optimisation of recovery. Specific risk factors for PGP during pregnancy were discussed in the first blog.

Vøllestad & Stuge (2009) looked at the predictors for recovery from PGP in regards to pain levels and disability. It wasn’t until this article in 2009 that researchers would investigating characteristics in antenatal women that would predict long-term disability or recovery from PGP.

- Oswestry disability index and pain are highly correlated postpartum i.e. the higher ratings of disability on the ODI were closely linked with pain levels. If this is the case, it begs me to question if we are using the ODI enough to identify those at risk of developing chronic pain? Or, are we using the ODI enough to measure long term recovery?

- An ASLR < 4 predicted lower pain scores and 19 points less on the ODI. “The results show that having ASLR score of at least 4 predicts ODI score ten points higher 1 year postpartum or pain eight points higher compared with those having ASLR score <4.” (Vøllestad & Stuge, 2009, p.722).

- Belief in improvement is closely related to pain levels.

- Having a history of LBP or emotional distress do not have predictive power on recovery. (Vøllestad & Stuge, 2009, p.721).

In summary

After reading this long and extensively researched clinical practice guideline I have come to realise that the amount of women affected by PGP during pregnancy is much higher than previously thought. There have not been a lot of changes made to the assessment of this condition with regards to physical impairment measures, but I have learnt that the PGP questionnaire and ODI may be more helpful than previously thought in identifying those at risk for long term pain and PGP postpartum. I was hoping to share concepts for interventions more strongly supported by evidence, however this is not available to us at this time. Instead, exercise, manual therapy and support devices continue to be recommended.

Most of the all, the clinician is reminded that much of this advice and these recommendations have to be applied case-by-case to evaluate the effectiveness of each approach. This must include education about why the exercises are helpful, how to perform them well and what the ideal outcomes are (painful exercise is not intended). Approaching exercise from this perspective will likely lead to improved compliance and better outcomes. Each individual requires and deserves an individualised assessment and personally-tailored approach to their rehabilitation. After all, no two pregnancies are the same and no two mothers have the same life demands/ADLs, and therefore cannot be treated as such.

Sian

References

Clinton, S. C., Newell, A., Downey, P. A., & Ferreira, K. (2017). Pelvic Girdle Pain in the Antepartum Population: Physical Therapy Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health From the Section on Women's Health and the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy, 41(2), 102-125.

Desmond, R. (2007). How women's health physiotherapists treat symphysis pubis dysfunction. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 31(1), 30.

Gutke, A., Östgaard, H. C., & Öberg, B. (2008). Association between muscle function and low back pain in relation to pregnancy. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 40(4), 304-311.

Hungerford, B., Gilleard, W., & Hodges, P. (2003). Evidence of altered lumbopelvic muscle recruitment in the presence of sacroiliac joint pain. Spine, 28(14), 1593-1600.

Hungerford, B., Gilleard, W., & Lee, D. (2004). Altered patterns of pelvic bone motion determined in subjects with posterior pelvic pain using skin markers. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 19(5), 456-464.

Mens, J. M., Damen, L., Snijders, C. J., & Stam, H. J. (2006). The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt in patients with pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Clinical biomechanics, 21(2), 122-127.

Mens, J. M., Snijders, C. J., & Stam, H. J. (2000). Diagonal trunk muscle exercises in peripartum pelvic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Physical Therapy, 80(12), 1164-1173.

Nascimento, S. L., Surita, F. G., & Cecatti, J. G. (2012). Physical exercise during pregnancy: a systematic review. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 24(6), 387-394.

Stuge, B., Lærum, E., Kirkesola, G., & Vøllestad, N. (2004). The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Spine, 29(4), 351-359.

Stuge, B., Holm, I., & Vøllestad, N. (2006). To treat or not to treat postpartum pelvic girdle pain with stabilizing exercises?. Manual therapy, 11(4), 337-343.

Vleeming, A., Albert, H. B., Östgaard, H. C., Sturesson, B., & Stuge, B. (2008). European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal, 17(6), 794-819.

Vøllestad, N. K., & Stuge, B. (2009). Prognostic factors for recovery from postpartum pelvic girdle pain. European spine journal, 18(5), 718-726.