Female Spin Bowler with Lumbar Stress Fracture

Working with the Melbourne Stars women’s BBL (big bash 20/20 cricket) and Vic Spirit teams has given me the opportunity to treat many lower back injuries associated with bowling. Although this is commonly attributed to fast bowlers, I have recently treated two spin bowlers with lumbar pain and/or lumbar stress fracture. I previously wrote a blog describing the management of a male spin bowler. This blog will look at a female spin bowler of similar age to the previous blog, comparing the difference between genders and amateur and elite cricket.

Introducing MARGARET

Margaret is a 23 year old spin bowler who presented with left sided lumbar/sacral pain, which she described as a deep ache with intermittent sharp pain and pins and needles along the L5 dermatome. This pain caused multiple (>5) episodes of waking in the night when rolling, resulting in poor sleep quality. Her pain was aggravated with most back movements, especially left side flexion, left rotation, bowling and walking. No previous history of injury, previously a good sleeper and nil medical history or medications.

Margaret is a spin bowler and had just returned from playing cricket in England during the Australian winter. This led me to question further about her bowling load.

Bowling load

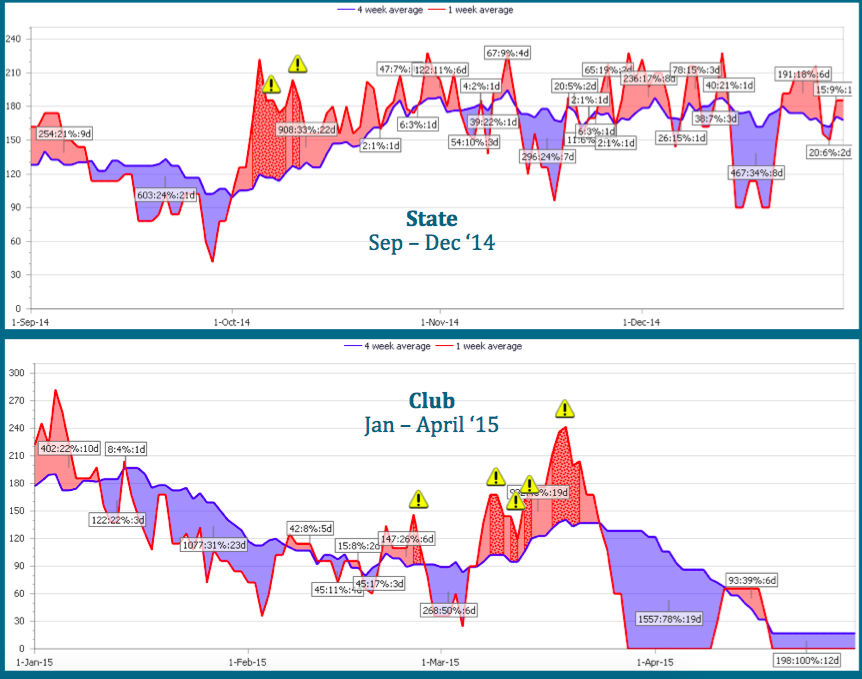

It appears her trigger for injury was poor management of bowling load. After breaking her training/playing schedule down into major time periods, the load looked like this:

- September 2014 - March 2015: Training 2 x week with 8 overs per session. 2 x strength and 2 x cardio gym sessions per week. Playing a game every weekend (either 20/20 or 50 overs). Bowling 26 overs/week = 156 balls/week.

- April - 4 weeks rest

- May 2015 -September 2015: Playing UK county women's club and men's club cricket. Training 2-3 x week bowling 7-10 overs. Same gym load. Playing 2 games a weekend with a 50/50 men's game on Saturday (10-15 overs) and women's game on Sunday (10 overs). Bowling 39-50 overs/week = 234-300 balls/week, double the bowling load of September to March.

It can be hard to understand the impact of these changes in training load and over that duration so they have been represented in the graphs below.

The red line shows the acute load (individual training sessions) while the blue load shows chronic load (average load in a month). The red line should only be about 20% greater than blue line at any point in time, otherwise you get "spikes". Yellow "!" signs represent an individual training session of 30% or more of the chronic load, recurrent spikes places an athlete at much higher risk of injury.

What does the evidence say?

- Players that have <2 days between bowling sessions at at significantly higher risk of injury (Dennis, 2003).

- In fact, bowlers who perform more than 5 sessions per a week of bowling have 4.5 times greater risk of sustaining injury (Dennis, 2004).

- In terms of overs, the research suggests that bowlers who perform <123 or >188 deliveries per week have a higher risk of injury (Dennis, 2003) and that fast bowlers who have a 200% increase in bowling load versus monthly load have a 3.3 times higher relative risk of injury (Hulin, 2014). This is all based on male cricketers, but gives a rough guideline of numbers.

Physical examination

- MRI: incomplete left L5 pars stress fracture with moderate bone oedema.

- PAIVMS: hypomobile L PA L5/S1 with reproduction of pain 5/10 and pressure pain on palpation consistent in location with MRI findings.

- Muscle palpation: increased tone through R quadratus lumborum (QL) and lumbar erector spinae (LxES), left ITB and vastus lateralus and left iliopsoas. Poor tone bilaterally through gluteus medius and maximus, medial gastrocnemius, VMO and abdomen. Trigger points through left gluteus medius and TFL, left upper QL and Lx ES, right piriformis and right ES.

- Functional: single leg squat - dynamic knee valgus (knee rolling in) ++ with bilateral excessive lumbar spine extension and anterior placement of weight.

- Muscle strength:

- Overactive upper abdominal muscles and poor lower abdominal control (unable to maintain neutral lumbar spine in "tabletop" position, laying on back with knees & feet in air)

- Quadricep fatigue after 20 second wall squat hold

- Gluteus maximus - assessed with a double leg bridge, fatigued 8 repetitions.

- Gluteus medius - sidelying abduction L=10 rep fatigue, R = 18 rep fatigue

- Single leg calf raise - L=8 rep fatigue, R=10 rep fatigue.

Bowling technique

Margaret uses various compensatory strategies to achieve force production - increased trunk sideflexion, leg "whip" to get hip propulsion, excessive left hip rotation (pivoting on left stance leg) & Trendlenberg on left stance leg (collapsing over the left leg).

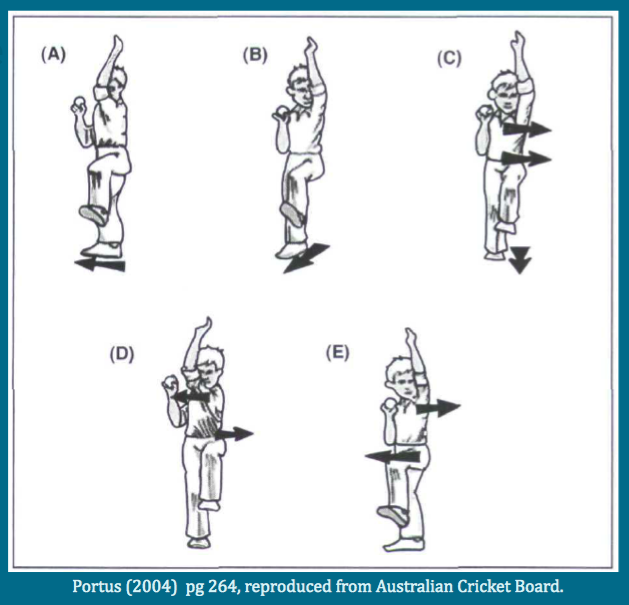

A - Side on. B- Semi-open. C - Front on. D - Mixed (shoulders more side on than hips). E - Mixed (shoulders more front on than hips).

There was a study conducted in 1989 by Foster et al, that looked at the injury rates associated with each technique:

- 9 side-on bowlers → one sustained a back injury (11%)

- 15 front-on bowlers → 8 sustained back injury (53%)

- 17 mixed → 6 sustained stress fracture (35.3%), 7 sustained soft tissue injury (41.2%) (76% total)

Other studies found that bowlers with mixed technique were more likely to show abnormal lumbar spine radiological features (Bartlett, 1996) . It has also been shown that female bowlers with low back pain history will adopt greater left lumbar side flexion on delivery stride & moved their thorax through greater range of side flexion during delivery stride compared to female bowlers with no history of low back pain (Stuelcken 2010).

After looking at these categories in technique we can look more closely at each style and relating this information to Margaret's case, we can see that her technique is a very prominent element of her injury risk and an area that needs to be addressed during her management.

How did we manage this player?

The current research has a strong emphasis towards conservative rehabilitation. Most patients with “symptomatic unilateral lumbar pars stress injuries” heal with conservative treatment. Ranawat & associates recommend “treating conservatively, with rest, supervised rehabilitation, bowling action analysis and re-education.” (2003. pg 915). Elliot found the assessment and modification of bowling technique decreased the incidence and/or progressions of lumbar spine disc degeneration (2002).

Hides (2008) described a program consisting of transversus abdominis, pelvic floor & multifidus co-contraction, progressing from supine to upright, with focus on a neutral lumbo-pelvic position and retraining of lumbo-pelvic dissociation. Their squat & lunge techniques were corrected, then after 6 weeks players were returned to their usual supervised gym sessions. This program resulted in increased cross sectional area of multifidus at L5, improved muscle asymmetry and a 50% reduction in pain. The article focuses on multifidus retraining, however the program retrains gym technique, enforces 6 weeks of active rest while the player completes a local stabilising program, then returns them to modified gym. Their gym program is only progressed if their technique is acceptable. The program is a very good rehabilitation program, however isn't isolated to multifidus.

Surgery is indicated only when symptoms persist beyond a reasonable time altering quality of life (Debnath 2007). Enforcing active rest, addressing strength and biomechanical deficits and modifying bowling technique appears to be the most appropriate management.

For Margaret there were three main goals for treatment: muscle strength, bowling technique and bowling load.

Exercise Rehab

Exercises given were very similar to the previous blog, please see the exercises for Tim here.

- Gluteals:

- We began gluteus medius and maximus training in isolation. Once technique was established the dosage changed to focus on endurance, then into functional positioning, functional endurance and finally functional strength.

- Abdominal Muscles:

- We began with isolated TrA activation, lumbopelvic dissociation and control. The next phase was again TrA endurance and then progression into functional positions were made.

- Oblique strengthening was also included in the strengthening aspect of the program and progressed from eccentric into concentric positions, replicating the action of bowling (pulling the right arm across the body to the left hip).

- Quad & Calves:

- Medial gastrocnemius training in isolation with emphasis on weight bearing through the great toe in full knee extension. Exercises were progressed into endurance, strength, functional endurance and final perturbations (with SLCR on a tramp with ball throws).

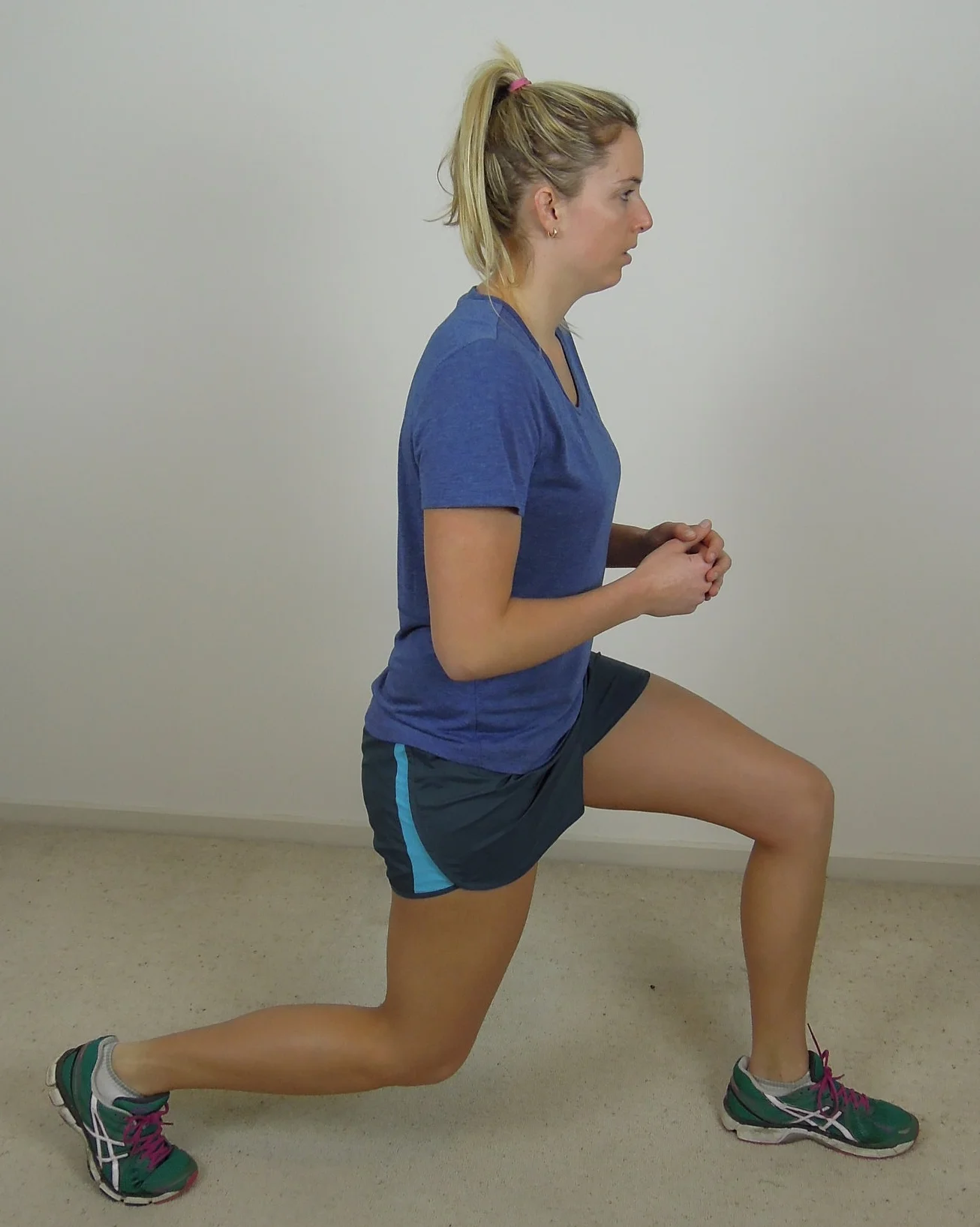

- VMO/Quads Complex were addressed with single leg squat on the TRX machine and SL squat with quads bias on the tramp.

See exercise examples here.

Bowling Technique

There were three main changes to bowling technique for Margaret:

- Foot Positioning:

- The right foot was planted at 45 degrees, encouraging a more side-on technique (which had reduced risk of injury).

- "Push up onto your right toes" to encourage pelvic rotation through the right lower limb kinetic chain.

- "Grow tall on left leg" to prevent Trendelenberg (right pelvis dropping).

- Pelvic Positioning:

- We tried to encourage neutral pelvic rotation with the cue "face your hips towards the wickets and drive through with your right hip". This prevents excessive rotation between the shoulders and pelvis and causes less hip internal rotation and less right leg 'whip'.

- We also aimed for neutral lateral and anterior pelvic tilt with the cue "grow tall". The aim was to prevent Trendelenburg and lumbar hyperextension and reduce the load through the lumbosacral region.

- Head & Thorax Positioning:

- Head neutral and aiming head for left edge of the wicket, “lead with your head” with the aim to encourage more torso control and keep her head up, to reduce uncontrolled side flexion.

Margaret is pictured below, following technique correction and 20 weeks post-diagnosis of stress fracture.

Bowling Load

Margaret returned to bowling, adhering to research completed by Gabbett, among others. Load was increased at 120-140% per week. Managing bowling load took 15 weeks to accomplish:

- Weeks 0-6: Active rest. Bike and swimming was started at 3 weeks. Completed activation & endurance exercises.

- Weeks 6-8: Above exercises progressed to higher levels, with exercises such as single leg calf raise on the trampoline. Margaret began full batting load & began running training. Bowling technique correction commenced, with focus placed on foot & pelvic positioning.

- Week 8: Follow-up MRI showed full recovery of stress fracture. Margaret was allowed to bowl from the crease (line on pitch, indicates no run-up) with 6 overs of shadow bowling (bowling motion without holding a ball, 36 balls) then 1 - 2 overs bowling with a ball, 3 times a week.

- Week 10: 1 over of shadow bowling as warm-up, followed by 3-6 overs off a full run-up, 3x a week. Margaret also played a club 50/50 game as a batter/fielder only (playing a one-day game), playing 2 games in 2 weeks.

- Week 12: 1 over shadow warm up. 6-8 overs with full run up, 3 x week. Played a club 20/20 games completing full batting & fielding, returning to bowling 4 overs (3 games in 3 weeks).

- Week 15: Played first WBBL (returned to elite level cricket) game batting, field and bowling 4 overs. Took 18 wickets at economy of 6.12, the highest in WBBL 01 season.

Take Home Message

The greatest difference between Margaret and Tim (previous blog) is the the ability to monitor and modify bowling load. It is very difficult to monitor bowling loads in the amateur population, however in elite level we have complete control over the player's rehabilitation and bowling capacity.

Correcting bowling technique was indicated, however Margaret's technique is now similar to her pre-injury technique. She has reported no back pain since returning to Big Bash, however her technique has not drastically changed. It appears monitoring bowling load, and increasing Margaret's activation, strength and endurance has prevented a recurrence of back pain.

While there is minimal research on lumbar stress fractures in spin bowlers, it seems research regarding fast bowlers can be extrapolated to spin bowlers. Monitoring and modifying bowling loads while addressing strength and endurance deficits (particularly of abdominal, gluteal, quadricep and calf muscles) was successful in returning both Margaret and Tim to pre-injury function.

In conclusion, addressing strength deficits and then implementing a graduated return to loading plan should return both amateur and elite spin bowlers to full function.

Alicia

References:

Bali, K., Kumar, V., Krishnan, V., Meena, D., & Rawall, S. (2011). Multiple lumbar transverse process stress fractures as a cause of chronic low back ache in a young fast bowler - a case report. Sports medicine, arthroscopy, rehabilitation, therapy & technology : SMARTT, 3(1), 8.

Bartlett, R. M., Stockill, N. P., Elliott, B. C., & Burnett, A. F. (1996). The biomechanics of fast bowling in men's cricket: a review. Journal of sports sciences, 14(5), 403-424.

Crewe, H., Campbell, A., Elliott, B., & Alderson, J. (2013). Lumbo-pelvic biomechanics and quadratus lumborum asymmetry in cricket fast bowlers. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 45(4), 778-783.

Crewe, H., Elliott, B., Couanis, G., Campbell, A., & Alderson, J. (2012). The lumbar spine of the young cricket fast bowler: an MRI study. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia, 15(3), 190-194.

Crossley, K. M., Zhang, W.-J., Schache, A. G., Bryant, A., & Cowan, S. M. (2011). Performance on the single-leg squat task indicates hip abductor muscle function. The American journal of sports medicine, 39(4), 866-873.

Debnath, U. K., Freeman, B. J. C., Grevitt, M. P., Sithole, J., Scammell, B. E., & Webb, J. K. (2007). Clinical outcome of symptomatic unilateral stress injuries of the lumbar pars interarticularis. Spine, 32(9), 995-1000.

Dennis, R., Farhart, P., Clements, M., & Ledwidge, H. (2004). The relationship between fast bowling workload and injury in first-class cricketers: a pilot study. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia, 7(2), 232-236.

Dennis, R., Farhart, P., Goumas, C., Orchard, J., & Farhart, R. (2003). Bowling workload and the risk of injury in elite cricket fast bowlers. Journal of science and medicine in sport / Sports Medicine Australia, 6(3), 359-367.

Dennis, R. J., Finch, C. F., & Farhart, P. J. (2005). Is bowling workload a risk factor for injury to Australian junior cricket fast bowlers? British journal of sports medicine, 39(11), 843-846; discussion 843-846.

Elliott, B., & Khangure, M. (2002). Disk degeneration and fast bowling in cricket: an intervention study. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 34(11), 1714-1718.

Elliott, B. C. (2000). Back injuries and the fast bowler in cricket. Journal of sports sciences, 18(12), 983-991.

Engstrom, C. M., & Walker, D. G. (2007). Pars interarticularis stress lesions in the lumbar spine of cricket fast bowlers. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 39(1), 28-33.

Engstrom, C. M., Walker, D. G., Kippers, V., & Mehnert, A. J. H. (2007). Quadratus lumborum asymmetry and L4 pars injury in fast bowlers: a prospective MR study. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 39(6), 910-917.

Ganiyusufoglu, A. K., Onat, L., Karatoprak, O., Enercan, M., & Hamzaoglu, A. (2010). Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography in stress fractures of the lumbar spine. Clinical radiology, 65(11), 902-907.

Hardcastle, P., Annear, P., Foster, D. H., Chakera, T. M., McCormick, C., Khangure, M., & Burnett, A. (1992). Spinal abnormalities in young fast bowlers. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 74(3), 421-425.

Hides, J., Stanton, W., Freke, M., Wilson, S., McMahon, S., & Richardson, C. (2008). MRI study of the size, symmetry and function of the trunk muscles among elite cricketers with and without low back pain. British journal of sports medicine, 42(10), 809-813.

Hides, J. A., Jull, G. A., & Richardson, C. A. (2001). Long-term effects of specific stabilizing exercises for cirst-episode low back pain. Spine, 26(11), E243-248.

Hides, J. A., Stanton, W. R., McMahon, S., Sims, K., & Richardson, C. A. (2008). Effect of stabilization training on multifidus muscle cross-sectional area among young elite cricketers with low back pain. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 38(3), 101-108.

Hides, J. A., Stanton, W. R., Wilson, S. J., Freke, M., McMahon, S., & Sims, K. (2010). Retraining motor control of abdominal muscles among elite cricketers with low back pain. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20(6), 834-842.

Hulin, B. T., Gabbett, T. J., Blanch, P., Chapman, P., Bailey, D., & Orchard, J. W. (2014). Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers. British journal of sports medicine, 48(8), 708-712.

Joyce, D. High-performance training for sports.

Kountouris, A., Portus, M., & Cook, J. (2013). Cricket fast bowlers without low back pain have larger quadratus lumborum asymmetry than injured bowlers. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 23(4), 300-304.

Maitland, G. D. (1991). Peripheral manipulation (3rd ed.). London ; Boston: Butterworth- Heinemann.

O'Sullivan, P., & Beales, D. (2007a). Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders--Part 1: a mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework. Manual therapy, 12(2), 86- 97.

O'Sullivan, P., & Beales, D. (2007b). Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders, Part 2: illustration of the utility of a classification system via case studies. Manual therapy, 12(2), e1-12.

Orchard, J. W., James, T., Portus, M., Kountouris, A., & Dennis, R. (2009). Fast bowlers in cricket demonstrate up to 3- to 4-week delay between high workloads and increased risk of injury. The American journal of sports medicine, 37(6), 1186-1192.

Ranawat, V. S., Dowell, J. K., & Heywood-Waddington, M. B. (2003). Stress fractures of the lumbar pars interarticularis in athletes: a review based on long-term results of 18 professional cricketers. Injury, 34(12), 915-919.

Ranson, C. A., Burnett, A. F., King, M., Patel, N., & O'Sullivan, P. B. (2008). The relationship between bowling action classification and three-dimensional lower trunk motion in fast bowlers in cricket. Journal of sports sciences, 26(3), 267-276.

Silbernagel, K. G., Thomee, R., Thomee, P., & Karlsson, J. (2001). Eccentric overload training for patients with chronic Achilles tendon pain--a randomised controlled study with reliability testing of the evaluation methods. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 11(4), 197-206.

Stuelcken, M. C., Ferdinands, R. E. D., & Sinclair, P. J. (2010). Three-dimensional trunk kinematics and low back pain in elite female fast bowlers. Journal of applied biomechanics, 26(1), 52-61.

Stuelcken, M. C., Ginn, K. A., & Sinclair, P. J. (2008). Musculoskeletal profile of the lumbar spine and hip regions in cricket fast bowlers. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine, 9(2), 82-88.