Smale Style

12 months after creating the blog Rayner & Smale, Alicia and I have posted 53 blogs, and we are hoping for many more in 2015.

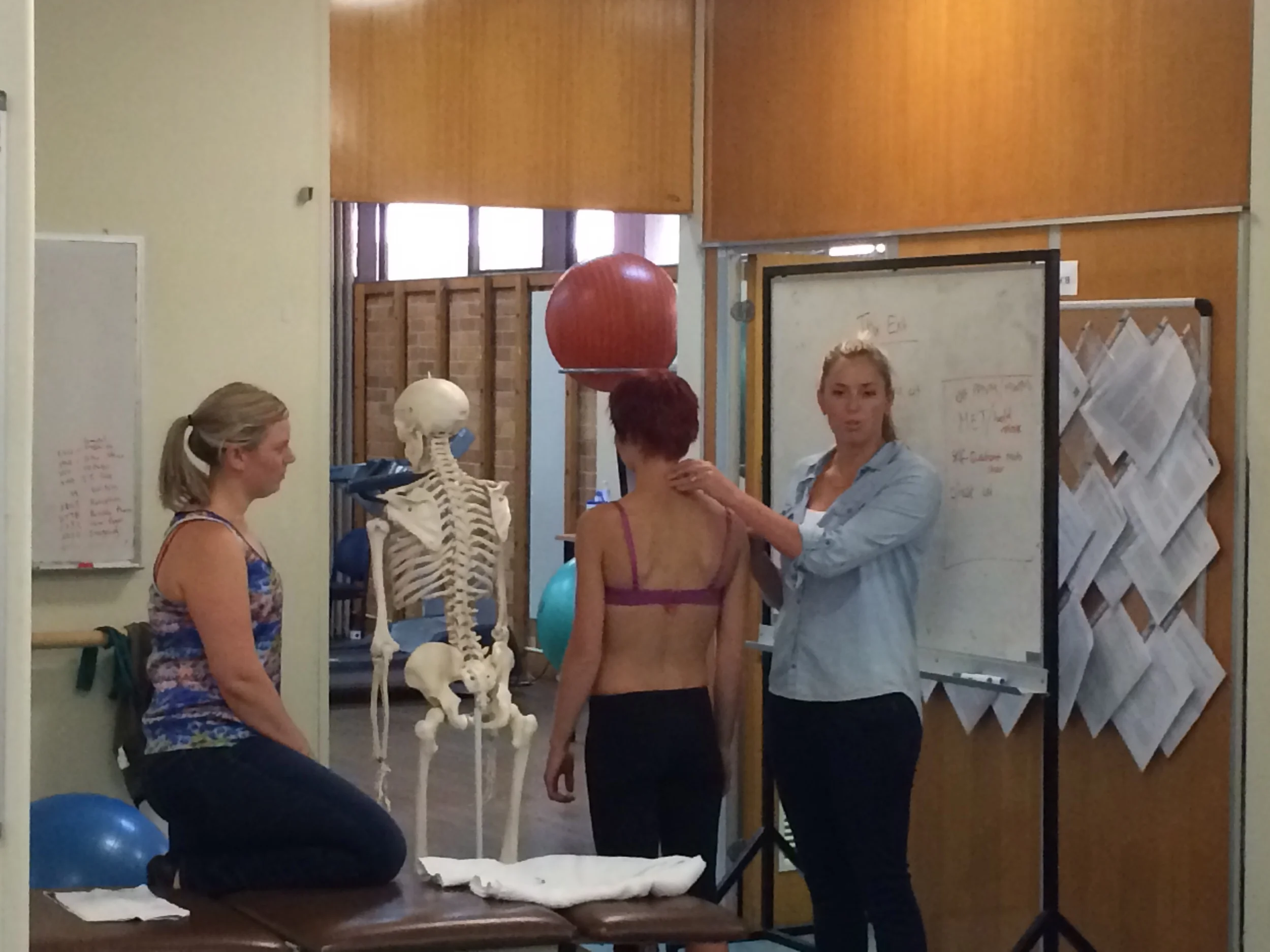

Teaching on Spinal level 2 with Alicia in Melbourne 2014

Moving to San Francisco has given me the privilege of focussing more time on our blog. Heading into my sixth year of practicing, I also feel that it is a great time to reflect on what the profession has taught me. It is no doubt a challenging profession physically, intellectually, and emotionally. Here are some of the lessons I have learnt over time which have significantly impacted how I approach my practice.

People always ask me "why physio?" Truthfully the answer is that my mum is a physio and my dad is a radiologist and both felt the profession would suit my nature. But why? Because I love helping others. I love caring for others, I have a deep curiosity and interest in the human body, science, nature and played a lot of sport growing up, and I love hugs (which implies I don't have a space bubble).

The real reason I love being a physio now is that I get to meet people and potentially change their lives by helping them in some way and often putting them on a new trajectory. And thats what drives my clinical practice and motivates me to write this blog. It is my greatest pleasure to know that I am helping others to expand their knowledge, to empower them with the tools to realise and reach their goals, to help them with their pain and struggles, and to provide motivation, strength, positivity, realism and knowledge.

I try to approach each day with the view that

- Everything happens for a reason.

- We all have something to learn from our encounters with others.

- Take time to look around and see the beauty that exists in the world.

Nature is beautiful and the human body and mind are both miraculous and mysterious. I am constantly in awe of what humans are capable of achieving.

The following points reflect my style as a clinician and educator:

Take the time to listen to your patients & truly understand their story.

I have been blessed to treat World War II veterans and hear the stories of their lives. They were exposed to more hardship and pain and suffering that many of us will ever see in a lifetime. One thing I have gained from these people is that they may be old and a bit deaf and riddled with problems (most of which you maybe can't changed) but the best thing I can do is to listen to their stories while treating them. I am endlessly learning from the generations before me.

Once I treated a survivor from the Japanese Prisoner of War camp. How did that come up in conversation? She presented with increased neck pain following a low-speed car accident and at the age of 85, with no fractures noted, the doctors told her it was normal wear and tear. She was entitled to some physiotherapy funding under TAC (Transport Accident Commission) and when I palpated her neck and said "this part of your neck is very stiff and feels like it has experienced an injury in the past" my patient replied "that is where I was repeatedly hit with the butt of a rifle during the war when I was a prisoner of war". Why am I sharing this with you? There is a reason for everything and often our patients are the best resource for finding out why things are the way they are.

Don't accept judgement from your patients.

The most common place I experience judgement is working in Women's health. Its sad to say it but mums often ask if I have children. And when I reply no, they respond that it would be hard for me to understand what they are experiencing.

This makes me sad and often defensive about my skills. I don't have children, I haven't experienced the challenges of pregnancy, child birthing and motherhood. But this doesn't change my ability to help mothers with their problems.

I don't need to have felt someones injury or experienced their pain to be able to help them. Often its better if I haven't so that I don't impose my personal judgements and beliefs on their problem. I went to uni for a reason - to teach me to know how to help people. Which leads me onto the next tip....

Empathy is more important than sympathy.

Empathy requires more than sympathy. As a clinician my goal is to understand how something is making you feel, not to share the same feeling or to have shared the same experience in the past. This doesn't mean that I don't genuinely care about the problem. It actually makes me more interested in how it is impacting your life.

I always try to be empathetic towards others and understand the challenges they are facing.

Being a physio can, at times, be a very emotionally and physically demanding profession. So....

Take time to do things for yourself everyday, even if it is simply enjoying a good cup of coffee.

Take care of your life & keep your balance.

Its ok to be sick or tired or take a mental health day - people are paying to seek help from you. If you aren't well enough to deliver that, then it isn't fair to them.

Be the change you want to see in others! Sleep well, exercise regularly, eat a balanced diet, and take holidays. Enjoy the time and the life that you have.

'Pain threshold' isN't a good measure of anything.

People often ask if it is difficult to understand the difference between each persons pain threshold? Firstly, I don't compare pain intensity from person to person, thats not fair. It is more important to understand how a problem impacts on someone's quality of life.

Using the WHO-ICF is a great way to break down the meaning of quality of life and to help set goals which are achievable and meaningful to each individual. This is based on the physical impairment, participation limitation and activity restrictions.

Along with understanding the impact of the problem on quality of life, I try to keep an open-mind about how the pain may lead to social isolation and disconnection from relationships.

I always question if the change I wish to see in my patients will actually lead to improved health outcomes. I generally aim to change their pain and find the source of symptoms (thats always so interesting and like being a detective), but I also focus on return of function, return to activity, and return to work. This is what often contributes more to their quality of life.

Choose words & language that empower & educate.

Avoid using metaphors for things we can explain with science and anatomy. There is no reason non-health professionals can't learn the real meaning for their pain.

If I can't explain to a patient what the problem is: pathophysiology, pathoanatomy etc, maybe I'm the best person to help?

If the patient can't explain to me what they have learnt, they are unlikely to retain the information and be compliant with my treatment recommendations. I have become more consistent is asking people towards the end of the session "What is your understanding of this problem?" or "If someone asked how your session was and what you learnt today, what would you tell them?"

Ask for help.

No one knows everything and most practitioners and colleagues are happy to help and share knowledge. Collaborative learning and knowledge sharing leads to faster growth both individually and as a professional. Early on as a physio I was always too nervous to ask for help. Now if I have a questions, a thought, or I'm confused, I share it with others. More often that not they have shared the same thought, already know the answer, or at least can direct me where to look.

The best source of information about the problem is always the patient - question them well.

Recognise barriers to change early

This is something I have found difficult to act on and it has taken many years for me to truely accept who I can/can't help and when there is a barrier that I won't be able to overcome by myself.

My supervisor once said there are 3 reasons for failure in treatment: the condition is not suited to recovery, the therapist hasn't provided the best available treatment, and the patient is not compliant.

I have had to learn to:

- Be open and confident to tell patients that maybe I can't help them and suggest what might.

- Be confident to cease treatment if no improvement in health outcomes is achieved.

- Alert patients to modifiable barriers to recovery - other co-morbidities, the need for additional therapies, work-place modifications, environmental and social factors, sleep, stress, diet, physical activity etc.

Use collaborative goal setting, motivational interviewing & holistic client-centred care.

- Be accountable. Be honest. Be genuine.

- Apologise for your mistakes

- Get the patient to set goals, help them to describe the change they want to see which would reflect improvement.

- I often have a different perspective of what "getting better" means and its always good to check what the expectations are of the patient.

- Those you seek help are looking for change. Understand their willingness to change, their ideal learning style and environment to achieve the best outcomes for them.

What does the pain mean to you and what are you afraid of?

Addressing patient's fear is so important to making them independent and self-managing. I hope to write a blog in the future about fear avoidance, but in short..... knowing what my patients are scared of it the tool I use to break through their barriers and to help predict flare-ups, to help promote self-management strategies, and to reconceptualise their understanding of the problem and what it means.

Celebrate the wins with a little smile from time to time

Celebrate the wins

One of my big downfalls as a physio is that I focus on my mistakes and I feel so terrible for the ones I can't help or have a less-than-optimal outcome. But on the flip-side of the coin, I have experienced some amazing wins and often don't spend a balanced amount of time recognising the good things which happen.

So now I'm trying to take on this perspective more....

We don't need to create miracles to make a difference in someone else's life. Sometimes it is powerful to celebrate with your patient to help them see that changes are occurring along the way. Without sounding cheesy (but it will anyway) life is about the journey and not the destination. Understand where each person wishes to go but share the journey with them, celebrate the wins, counsel them through the flareups and help to guide the way forward. Give your patient a fist-pump, a pat on the back or even say 'boom' or 'crushed it'. What ever floats you boat really. We are trained to see the clinically-significant changes which lead us to the destination.

Approach each day with love, gratitude and a drive to learn from what life has to teach us. Sian