Lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy - a case study

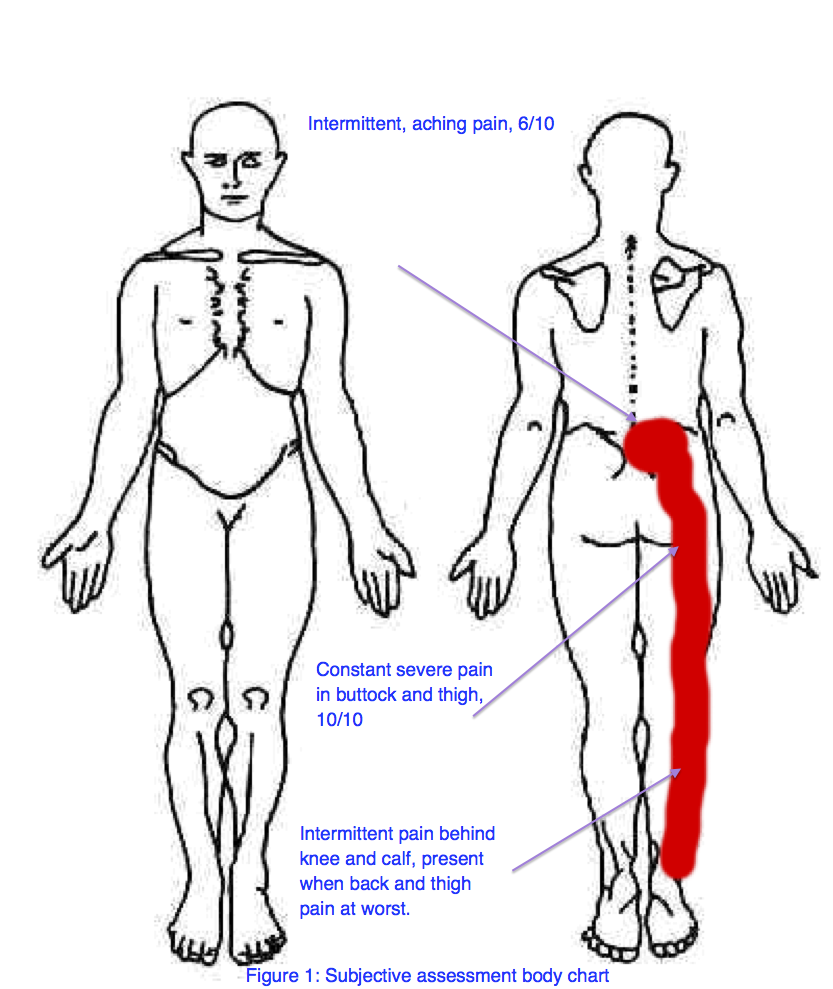

“Sally”, was a 23-year-old Swedish backpacker who presented with a three-month history of low back pain and more recently right leg pain. Sally was referred from the Emergency department to Outpatient Physiotherapy within a large public hospital. She had presented to ED on six occasions since May for worsening pain.

Mechanism of injury

Sally couldn't recall a single event relating to the onset of her back pain. In the weeks prior to developing back pain she had been working casually as a waitress and did find bending over tables a strain. The pain began in her lower back quite centrally and with time is starting radiating straight down the back of her right thigh and into her calf, stopping at the ankle.

Current symptoms

24 hour pattern:

- Worse in the morning. She feels stiff and crooked in the am, is unable to get out of bed without assistance (from friend), and requires help to shower and dress.

- Waking in the night every 2-3 hours with severe buttock and posterior thigh pain.

- Denies any pins and needles or numbness but her right leg has become heavy.

Aggravating/easing factors:

- Lying down, sitting down, being still or getting cold aggravated her back and leg pain.

- Pain levels pain levels increase within 30 minutes of each sustained posture and take up to 2 hours to ease (mostly through walking).

- There was no position or movement that completely reduced Sally’s leg pain.

Investigations, medications & current treatment:

- Lumbar spine CT reported a L5S1 disc protrusion with right S1 nerve root compression.

- Valium, Endone, Panadeine forte and Ibuprofen had been prescribed whilst in ED, of which Sally continued to take panadeine forte and ibuprofen in their maximum daily dosage.

- Sally also received three treatments from a private Osteopath consisting of lower back and buttock massage. Although it felt ok at the time, there was no sustained improvement in pain and function.

General health & social history:

- Her general health was unremarkable and there were no other red flags within the subjective assessment.

- She was working casually as a waitress, however had to quit her job due to worsening pain.

- As she can’t work, Sally wished to return home to Sweden, however was worried she wouldn't be able to travel back home in her current pain state.

- Sally expressed her concerns regarding her pain and the lack of improvement, and especially was perplexed about the cause of her problem.

Subjective assessment analysis

Following the subjective assessment my primary hypothesis for the source of symptoms was a lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy (LDHR). More specifically L5/S1 disc protrusion with right S1 nerve root compression (as per CT Scan results).

Reasoning for hypothesis is based on:

- Distribution of pain following the S1 dermatome.

- High pain severity of 10/10 in the leg and 6/10 in the back i.e. worse distally.

- Moderate irritability (no position of ease, takes 2 hours to settle slightly).

- Strong inflammatory nature to her morning pain and stiffness.

There is no single feature that provides the diagnosis of lower limb radiculopathy (often referred to as sciatica), but more research suggests a with a combination of the following features diagnosis of LDHR is more specific (Ford, Hahne, Chan, & Surkitt, 2012; Jacobs et al., 2011; Koes, Van Tulder, & Peul, 2007; Van der Windt, et al., 2010).

- Distribution of symptoms

- Unilateral leg pain greater than low back pain.

- Pain radiating in a dermatomal pattern, below the knee and into the foot or toes.

- Numbness and paraesthesia in the same distribution,

- Positive signs on neurodynamic and neurological examination

- Straight leg raising test induces more leg pain.

- Neurological deficits which are limited to one nerve root.

- Positive signs on MRI and CT imaging of lumbar disc herniation resulting in nerve root compression

Hypothesis testing

In order to prove my primary hypothesis it was necessary to determine if there were positive signs on the straight leg raise test and neurological deficits on the physical examination. The secondary hypothesis, which needed to be ruled out, was somatic referred pain, which could be implicated or disregarded following the neurological and physical examination (Van der Windt, et al., 2010).

Physical examination

Observation of posture and function:

A picture of me trying to demonstrate the posture of Sally on initial presentation. Sometimes its not this obvious and if I am not sure if there is a list present, I run my fingers down the spinous process' to double check. This is when I find the small lists which aren't observable but still clinically relevant and respond well to list-correction strategies.

- The first thing I noticed was the way Sally stood.

- In standing, her shoulders were shunted to the left side, her back was extended and pelvis anteriorly tilted, and there was visible hyper-tonicity of the lumbar para-spinal muscles.

This shunted antalgic posture is commonly referred to as a lumbar list. Observation of a lumbar list unfortunately is a test lacking in reliability (Clare, Adams, & Maher, 2003). Maitland (2005), however, teaches us that if a person presents with an observable postural deformity, they are going to be more challenging to get better. In Sally’s case, she had a contralateral list (shoulders listed to the opposite side of back/leg pain), which is thought to respond more favourably to treatment than an ipsilateral list.

In my experience antalgic postures are very important to detect because they indicate a protective position; mechanism which the body is adopting (often subconsciously) in the acute phase of injury to protect the injury, and if the antalgic posture is not carefully examined and carefully corrected, it can make the patient a lot worse. This is often seen when a patient comes in to an appointment saying “my back is out of alignment” and when the posture is corrected, instead of being better, they can’t get of the treatment table…..

Active range of movement:

- Lumbar flexion P2 (right-sided low back pain) R`(upper thigh).

- Extension P2 (right buttock and leg pain) R` (vertical).

- Other movements were not assessed day 1 due to severity and irritability.

Neurological examination:

- Weak single leg calf raise (SLCR) and was only able to perform three assisted raises to 50% range. Gr 5 strength of right leg SLCR x5 repetitions.

- No other myotomal weakness was detected.

- The S1 reflex on the right side was absent, with other lower limb reflexes being preserved.

- No sensory changes were noted.

Neurodynamic examination:

- The straight leg raise test (SLR) was positive in reproducing Sally’s posterior thigh pain and limited at 20 degrees on the right side.

- Her left SLR was limited by hamstring tightness at 50 degrees.

The research suggests the SLR a reliable re-assessment asterisks for patient progress. It has been show to be 91% sensitivity and 26% specificity in detecting lumbar disc pathology (Jensen, et al., 1994). Deville et al. (2012) found that more than a 11 degree discrepancy in hip flexion range between sides was a clinically significant result. Compared to MRI, the SLR test has poor diagnostic accuracy, and therefore is often used in conjunction with such imaging.

Manual palpation:

- Palpation was conducted in the left side lying position with pressure applied only to the onset of pain (P1).

- The presence of generalised hyperalgesia made it difficult to establish a comparable finding day 1.

Analysis of physical examination & primary hypothesis

The hypothesis of L5/S1 lumbar disc herniation with associated S1 radiculopathy was accepted, based on:

- Presence of pain distribution along the S1 dermatome,

- Absent S1 reflex,

- Weakness of the S1 myotome,

- Positive right sided SLR,

- and correlation between these physical findings and the results of the lumbar CT scan.

Treatment

Day 1 treatment:

- List correction with left side gliding exercises in standing.

- This was indicated during the physical exam as an effective pain reducing technique.

- The result of this treatment was // reduced LBP and increased Lx ext AROM, reduced list in standing, and less pain with walking.

Directional preference mechanical loading strategies (MLS) have been derived from the McKenzie method and are a common approach implemented in the treatment of discogenic low back pain (Ford, Surkitt, & Hahne, 2011). The key feature of using MLS in assessment and treatment is the centralisation phenomenon, i.e. abolishment of distal symptoms as a result of repeated movements of the lumbar spine. Applying this principle of MLS, I chose left side glide as my direction of treatment as it resulted in centralisation of Sally's leg pain.

Typically when patients present with a list and large restrictions in flexion and extension movements, I choose side gliding. We know that the IVD has poor blood perfusion and gets nutrients for healing more from movement. Often I explain to patients "the injury you have will heal quicker if we can find a way to get you to move frequently and move without too much pain". From here I assess side gliding (and its normally only one direction to start) and will use list correction as a treatment if there is a favourable outcome from the mini-treatment. Using this movement to show patients that they can manage their pain, that movement is healthy, and that they don't have to be a stiff plank for several days.

By placing the elbow against the wall it supports the trunk and allows the side gliding movement to be localised to the lumbar spine. Ask the patient to move their hips towards the wall stopping at the first point or discomfort or pain. Often on Day 1 this is only completed on one side.

Taping was used as a second treatment day 1. This was justified as a means of maintaining the improved spinal position, reducing load through the disc and ultimately reducing inflammation (Ford, et al., 2012; Ford, et al., 2011).

If there is a movement direction that is particularly painful, I try to limit that movement on the first day. So, move into the direction that feels good and try stay away from provoking pain in the movement that hurts more. Thats not to say that all forward bending should be avoided, just know the limitation to range and respect that.

Taping in a criss-cross overlap with help reduce muscle activation across the lower back. I use this taping when I feel patients need to be supported and unloaded. (I always use fixomull first to reduce any skin irritation from the pull I place on the strapping tape to unload the spine - not shown well here).

Taping with vertical strips will block lumbar flexion. I use this taping when I am trying to increase proprioception and patient awareness about their lumbar flexion during functional movements.

Advice was the final component of the day 1 treatment, which included:

- To avoid prolonged bet rest and sitting, & to go for regular small walks to help manage the stiffness.

- Education for the expected timeframes for recovery (months) and likely prognosis (determined by progress and reassessment Day 2/3) to enhance self-management and to reduce the likelihood of re-aggravation.

The use of three different treatment strategies for the first treatment can be justified by:

- The chronic nature of the pain,

- Worsening symptoms,

- Lack of response to previous treatment

- The patient’s poor understanding of the problem.

The primary goal of the day 1 treatment was to determine if any change could be made through physiotherapy, or if the patient was likely to require a neurosurgical consult. Choosing three treatments might be considered over-treating in some cases, but I'm sure most will agree that treatment of back pain is multi-faceted and I always aim to change the pain, empower the patient and do enough to confirm my understanding of the problem. Also, I believe these treatments compliment each other rather than competing to achieve the same goal.

Severe radicular pain in combination with a positive SLR and more than one area of neurological deficit are indicators that warrant a neurosurgeon assessment (Koes, et al., 2007). Therefore, several steps were taken to ensure that enough treatment was completed to demonstrate a true change in symptoms. At this time the patient was flagged with the neurosurgery clinic, who would wait for an update on patient response to treatment.

Day 2 assessment and treatment

Lets go through this a bit quicker…..

Subjective assessment

- Reported improvement in LBP with back pain 4/10 and leg pain 7/10 (almost 30% improvement).

- Am stiffness continued but Sally was able to independently get out of bed and move around.

- No symptoms of leg heaviness.

Physical examination

- The following physical asterisks were re-assessed:

- Contralateral lumbar list in standing – improved but still remained (slightly),

- Lumbar AROM – Flex P2(right LBP) R(mid thigh) and extension P2(Right LBP) R(10 degrees).

- New assessment: Lx LF P2(R LBP) R(mid thigh) L=R.

- SLR and SLCR- unchanged.

- New assessment – Motor control of Transversus Abdominus (TrA).

- Based on the fact that taping helped to increase the sense of stability around the lumbar region, I was interested to explore if activation of stabilising muscles could produce the same treatment effect.

- This was assessed in standing, with the addition of TrA activation prior to, and throughout lumbar active movements and in supine as a variation of the active straight leg raise test.

- In both position Sally reported increased pain following activation of these muscles. This assessment was then abandoned. Not because it was wrong but because it provided no route for new treatment on day 2 . It may be re-visited in subsequent treatment sessions.

- Second new are of assessment - Lumbar passive physiological intervertebral movements (PPIVMS).

- Assessment revealed a deficit in rotation movement between L5 and S1 segments on the right side, limited by pain.

- This was treated with Gr III- rotation mobilisations at 30-second intervals.

- On reassessment, there was a reduction in pain at 10 degrees of lumbar extension AROM and reduction of thigh pain with walking.

- As Sally had improved, day 1 treatment was repeated with review of the list correction exercise and re-application of a the lumbar tape.

Treatment progression and prognosis

Sally had been symptomatic for three months and had several neurological deficits. Following two treatments, Sally was showing encouraging signs of improvement (in pain and function, not neurological signs) with conservative care. If this improvement continued she is likely to have the same prognosis of pain reduction and recovery of disability & function, with conservative treatment, when compared to lumbar microdiscectomy at 1-2 years post injury (Jacobs, et al., 2011; Peul, et al., 2008).

A systematic review of conservative management of LDHR found that there is only moderate evidence to support stabilisation exercises over no treatment, and manipulation over sham manipulation (Hahne, Ford, & McMeeken, 2010). These authors believe that the poor results are not a true reflection of the treatment modality and often negatively impacted by the heterogeneity of the sample population. Further research is currently being conducted. The results of the specific treatment of problems of the spine trial (STOPS) have not yet been published, however, the Hahne and collegues (2011) hypothesise that specifically tailored treatments will achieve more superior results. A previous blog explores aspects of this trial further - 'An interview with John Ford and Rob Laird'.

Ford, et al. (2012) suggest that a functional rehabilitation program is the most suitable treatment for Sally’s problem, which include the following features:

- Restoration of capacity for activities of daily living including work,

- Negotiation of meaningful goals,

- Development of graded exercise program of functional tasks to increase psychological and physical tolerances,

- A focus on increasing strength, flexibility and cardiovascular fitness, and

- A cognitive-behavioral approach to address psychosocial barriers to achieving goals.

Conclusion

- The primary hypothesis of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy needs to be supported by a combination of physical examination findings, and correlate with the results of MRI or CT scan.

- If Sally’s condition deteriorated, she has enough signs of compressive radiculopathy to warrant a neurosurgical review.

- Following the initial phase of treatment and resolution of the lumbar list, a functional restoration program is likely to be with most relevant treatment approach for this problem.

- Given the improvement shown within the first two sessions, and in light of the evidence, Sally will likely have a good prognosis for recovery, and in the long-term regain her pre-morbid level of function.

How would you manage a patient who presented with this problem? I love to hear about your approach to the first few treatment sessions and explore other clinical reasoning processes and hypothesis testing methods.

Sian

Bibliography

Boyd, B. S., & Villa, P. S. (2012). Normal inter-limb differences during the straight leg raise neurodynamic test: a cross sectional study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 13(1), 245.

Clare, H., Adams, R., & Maher, C. (2003). Reliability of detection of lumbar lateral shift. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 26(8), 476-480.

Devillé, W., van der Windt, D., Dzaferagic, A., Bezemer, P., & Bouter, L. (2000). The test of Lasegue: systematic review of the accuracy in diagnosing herniated discs. Spine, 25(9), 1140-1147.

Ford, J. J., & Hahne, A. J. (2013). Pathoanatomy and classification of low back disorders. Manual therapy, 18(2), 165-168.

Ford, J. J., Hahne, A. J., Chan, A., & Surkitt, L. D. (2012). A classification and treatment protocol for low back disorders Part 3‐Functional restoration for intervertebral disc related disorders. Physical Therapy Reviews, 17(1), 55-75.

Ford, J. J., Surkitt, S. L., & Hahne, A. J. (2011). A classification and treatment protocol for low back disorders Part 2‐Directional preference management for reducible discogenic pain. Physical Therapy Reviews, 16(6), 423-437.

Hahne, A., Ford, J., Surkitt, L., Richards, M., Chan, A., Thompson, S., et al. (2011). Specific treatment of problems of the spine (STOPS): design of a randomised controlled trial comparing specific physiotherapy versus advice for people with subacute low back disorders. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 12(1), 104.

Hahne, A. J., Ford, J. J., & McMeeken, J. M. (2010). Conservative management of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy: a systematic review. Spine, 35(11), E488-E504.

Jacobs, W. C., van Tulder, M., Arts, M., Rubinstein, S. M., van Middelkoop, M., Ostelo, R., et al. (2011). Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. European Spine Journal, 20(4), 513-522.

Jensen, M. C., Brant-Zawadzki, M. N., Obuchowski, N., Modic, M. T., Malkasian, D., & Ross, J. S. (1994). Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. New England Journal of Medicine, 331(2), 69-73.

Koes, B. W., Van Tulder, M. W., & Peul, W. C. (2007). Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 334(7607), 1313.

Maitland, G. D., Hengeveld, E., Banks, K., & English, K. (2005). Maitland's vertebral manipulation: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann Edinburg.

Peul, W. C., Brand, R., Thomeer, R. T., & Koes, B. W. (2008). Improving prediction of “inevitable” surgery during non-surgical treatment of sciatica. Pain, 138(3), 571-576.

Van der Windt, D. A., Simons, E., Riphagen, I. I., Ammendolia, C., Verhagen, A. P., Laslett, M., et al. (2010). Physical examination for lumbar radiculopathy due to disc herniation in patients with low-back pain (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2(2).