Patella Tendinopathy & the 4-stage management program for 'Jumper's knee'

To continue on the tendinopathy series for October, I'd like to touch on the current management strategies for patella tendinopathy. I've enjoyed reading so much excellent research around this topic. May favourite authors Jill Cook, Peter Malliaras, Craig Purdam and Ebony Rio have been pumping out some killer research papers over the past few years. These authors are also combining forces with our best pain scientists, like Lorimer Moseley, to try understand what pathological process leads to tendon pain and how we can best treat this difficult condition. My aim for this blog is to introduce to you the papers that have helped me learn the most and to explore a proposed management program for patella tendinopathy.

Clinical presentation

Patella tendinopathy is defined as pain and dysfunction in the patella tendon. Clinically, patella tendinopathy presents with localised anterior knee pain and pain with loading tasks such as stairs, jumping, squats, sit to stand, and prolonged sitting (Rudavsky & Cook., 2014).

The following clinical features help support our clinical reasoning and are consistently reported throughout the literature (Malliaras, et al., 2015; Rio, et al., 2015b; Van Ark et a., 2014:

- Pain over the inferior pole of the patella.

- Load-dependent nature.

- Warm up phenomenon - stiff to warm up but eases with activity.

- Increased pain the day after activity.

- Pain increases as load increases i.e shallow to deep squat, hopping from a greater height, walking down stairs, decline squat.

- Pain is rarely experienced at a resting state.

- Patella tendinopathy is rarely associated with global swelling.

This condition is more highly prevalent in athletes that participate in activities demanding energy storage and release from the tendons, with volleyball player being the most effected population. The biggest extrinsic risk factor is thought to be training volume and frequency, and the intrinsic risk factors are thought to include reduced extensibility in the quadricep and hamstring muscles, a more vertical 'stiffer leg' landing pattern, low arch height, reduced ankle dorsiflexion, leg length discrepancy, patella alta and increased waist circumference in men (Rudavsky & Cook, 2014).

When thinking about volleyball players it is important to understand the role each athlete has on their team and the sport-specific demands on their position in order to determine the tendon-load requirements. Specifically relating to volleyball, players spend large amounts of time in knee flexion with squatting and diving onto their knees (depending how good they are at the dive). So there are elements of compression, blunt trauma and sustained load under flexion which can contribute to this presentation.

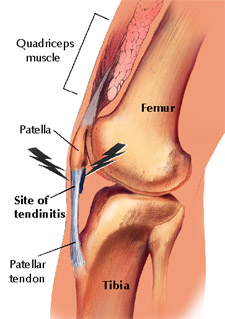

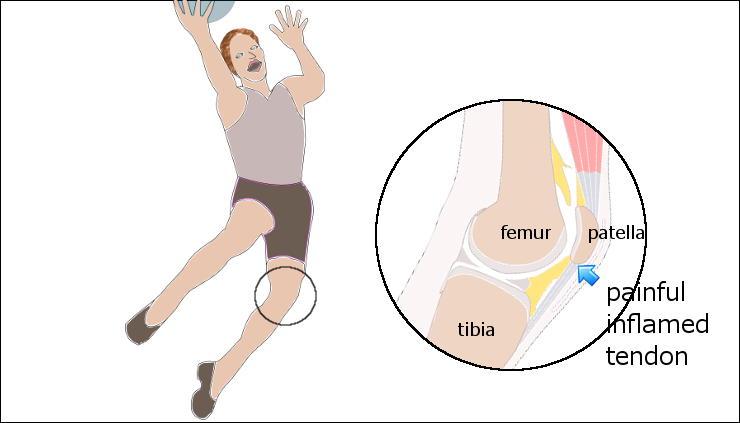

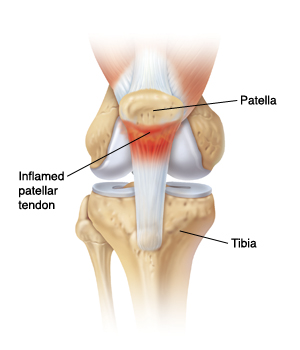

I typed 'Jumper's knee' into google images to see what came up during my background research and the first few images used 'inflammed tendon and tendinitis' in their description. Although the third image depicts quite well where the pain is felt when referring to the inferior pole of the patella, let's be clear that the terms "tendinitis" and "inflammed tendon" are no longer used. There is no inflammatory process occurring in tendinopathy. Tendinopathy is thought to occur from overload and there are three phases in the continuum of pathology known as reactive tendinopathy, tendon dysrepair and tendon degeneration.

Considerations for differential diagnosis.

There are many conditions that result in anterior knee pain and dysfunction during loading, therefore clinicians need to rely heavily on their clinical reasoning in order to accurately identify the source of the pain. "The most commonly involved structures in non-traumatic presentations of knee pain are thought to be the patellofemoral joint and patellar tendon; however, the contribution of the fat pad to nociception and incidence of other diagnoses such as plica are unknown” (Rio et al, 2015a, p. 1).

When going through your differential diagnosis try to remember that the "hallmark features for the diagnosis of patella tendinopathy are pain localised to the inferior pole of the patella and load-related pain that increases as demand on the knee extensors increases, notably with activities that require the storage and release of energy from the tendons" (Malliaras, e al., 2015, p. 1-3).

HAVE YOU LOOKED AT THE KINETIC CHAIN?

- Atrophy in the anti-gravity muscles - quadriceps, calves and gluteals - these can be assessed with common tests such as single leg bridge, single leg squat, repeated knee extension and single leg calf raise.

- Flexibility and posture - mobility of the hamstring (SLR), weight bearing ankle dorsiflexion and foot posture.

- Functional assessment - for jumpers hopping and vertical jump to determine energy storage strategies, landing strategies and biomechanics. You may notice that if they have knee pain they are stiff in landing, or if they have really stiff ankle they land with too much knee flexion. Also if volleyball players are wearing ankle braces I would strongly suggest assessing them barefoot and in their normal shoes to show the difference in biomechanics.

Rudavsky & Cook, 2014, p. 125

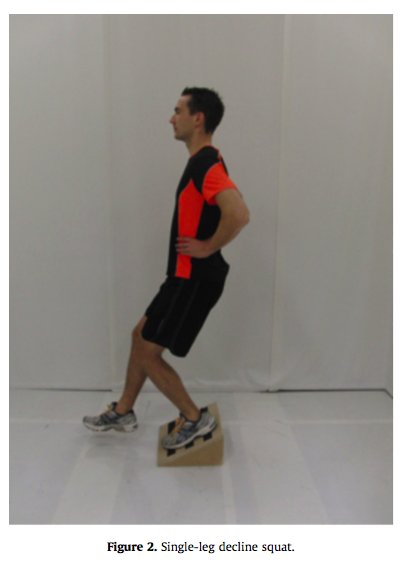

SINGLE LEG DECLINE SQUAT

Throughout the literature the single leg decline squat has been used to evaluate pain under load. It is used to determine if there is pain at 60 degrees knee flexion and a 0-10 rating of pain is gained during the test. Many authors will highlight that this test is not sensitive to different causes of anterior knee pain and therefore as a single test, holds poor diagnostic utility (Purdam, et al., 2004; Rio, et al., 2015; Van Ark, et al., 2014). It is often used in conjunction with the loading history, location of pain, strength and range of movement assessment and functional measures like the 3-hop test and vertical jump test.

The decline squat test is performed on a 25 degree angles board and the reason for this is that the repositioning of the ankle reduces the demands of dorsiflexion and is thought to load the patella tendon more than the patellofemoral joint in this position, and more than when compared to a single leg squat on flat ground.

What is the role of Medical imaging?

Medical imaging such as ultrasound and MRI are used to assist with the differential diagnosis of anterior knee pain (Malliaras, et al., 2015; Rudavsky & Cook, 2014). We don't always use it to try diagnose this problem but to look for other causes of pain and we don't often use ultrasound as a first line treatment because there is a disconnect between imaging and pain for patella tendinopathy (Rudavsky & Cook, 2014). What this means is that painful tendons can have normal imaging and pathological tendons on imaging can be asymptomatic.

Malliaras & Cook (2006, p. 390) describe two possible explanations as to why tendon pain can exist without tendon pathology:

- The first is that the presence of biochemical factors such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide which may cause tendon pain, and

- The second, is that there may not be any pathology seen on imaging because the pathology exists elsewhere like the peritendinous tissues.

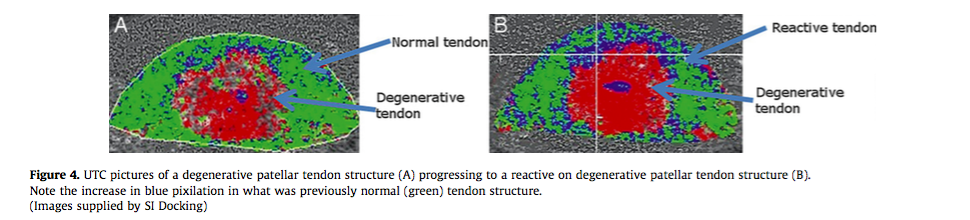

This is what ultrasound looks like (Rudavsky & Cook; 2014., p. 126)

How does the brain (Corticospinal activation) impact muscle control?

The was an interesting study (Rio, et al., 2015a) which explored the control of quadricep activity in 29 male volleyball players who participate in jumping activities at least 3 times week. They were allocated to three groups: no pain, patella tendinopathy, and other causes of knee pain. The authors used electromyography and transcranial magnetic stimulation to measure the activation of the quadricep muscles during a maximal voluntary isometric knee extension contraction tested in a position of 90 degrees hip flexion and 60 degrees knee flexion.

The authors hypothesised that there would be a difference in corticospinal activity between patella tendinopathy and other causes of anterior knee pain and in fact they were correct. Their study showed that people with patella tendinopathy have elevated activity with activation of rectus femoris. These abnormalities in excitation of the rectus femoris provide insight that treatment should focus on retraining the quality of quadricep activation. People with patella tendinopathy are likely to have an inability to successful grade their activation pattern and might over-shoot or under-shoot the activation pattern. So it’s not all about strength - timing and quality of activation might be the next focus we add into our treatments of this condition. They suggest that this might occur as a protective mechanisms, it’s not due to an alteration in motor activation thresholds, ….. why these corticospinal changes are occurring still remains to be determined. It could be speculated however that these alterations in motor control can lead to aggravation and overload of the tendon so once again we come down to the “chicken or the egg” hypothesis. None the less - when you next examine a client with anterior knee pain and are suspecting patella tendinopathy as your diagnosis be sure to look at both the strength and quality/timing of quadricep activation and the motor patterning between sides and be sure to look at contributing factors outside the tendon itself.

What challenges will you face?

There are many challenges faced by Physiotherapists for the management of patella tendinopathy (Malliaras, Cook, Purdam & Rio, 2015). One of the biggest difficulties in managing patella tendinopathy is creating an effective treatment plan for reducing knee pain during season. There is mounting evidence suggesting that our traditional eccentric exercises (decline single leg squat) may actually lead to increased knee pain when implemented as a treatment with-in season (Van Ark, et al., 2014). The reason eccentric exercises have been previously used is because research into other tendons in the body has suggested it might be a helpful treatment (Rudavsky & Cook, 2014). Before we even get to the treatment protocol, there are other challenges that Physiotherapists should be aware of, which include the following:

- Differential diagnosis to determine the source of the pain.

- Determine the irritability of the tendon. If the pain settles within 24 hours of activity then it is thought to be stable, if not, irritable.

- Looking at the entire kinetic chain.

- Deciding what treatment to use.

- Accurately educating clients and other stake-holders about realistic rehabilitation timeframes.

What treatment will you choose?

- Decline squats have been shown to be potentially too aggressive for an irritable tendon. Despite the large amount of research on eccentric exercises for this condition there is little support of this approach (Malliaras, et al., 2015, p. 9)

- Have you addressed other weakness in the chain? Like calf weakness and gluteal weakness which both impact the control of knee movement and amount of knee movement recruited.

- What about a heavy-load slow movement program? This helps to improve strength without overloading the ‘spring loading and energy storage capacity' of the the tendon.

- Leg press, Hack squat, Slow concentric-eccentric squat

- Performed 3-4 sets or 15 reps of maximal repetitions to 6RM

- This program has much higher patient satisfaction (70%) compared to the decline squat program (22%) (Malliara, et al., 2015, p. 9)

How long will rehabilitation take?

I think typically therapist’s might not realise how long it takes to successful treat patella tendinopathy. Perhaps this is why successful return to sport is so low? Can we do better at promoting a better rehabilitation protocol? Educating the client and their coach about the timeframes so you are all working collaboratively towards the same goals? There are so many ways we can achieve this.

Set realistic short term goals:

- Get your pain to settle within 24 hours of activity.

- Avoid complete rest.

- Gain enough strength for 8 RM on the affected side before progressing to hopping.

Manage their beliefs and correct poorly informed knowledge:

- There is no inflammation.

- The tendon is often not torn or permanently damaged (this often distills the belief that nothing can be done and for endurance copers, some athletes can push through without properly adhering to treatment suggestions).

- We can’t afford to ignore pain avoidance behaviours nor can we tolerate poor pacing strategies. The more they understand that pain will be present and it is an expected part of recovery and teach them how to use the pain to guide their recovery - the compliance with improve.

- Pain doesn’t equal harm. How well can you educate patients about the current model of pain and the biopsychosocial model. Explaining that pain is part of the body’s protectometer and that it is influenced by lifestyle factors, immunity, sleep, diet, social factors and many other things.

Educate them about load: Load is good and we need load to recover. We just need to pick the right amount of load.

Encourage an internal locus of control:

- Reducing a dependence on passive treatments. They can be useful but have to be used in combination with exercise treatment and education.

- Often we try too quickly and painful tendons can take up to 6 months to fully recover to the level the athlete wants to return to (Malliaras, et al., 2015).

A 4-stage rehab program for the management of patella tendinopathy

Now we get to the juicy section of this blog - the treatment which is thoroughly outlined in the article by Malliaras & colleagues (2015). This is a fantastic paper with some amazing clinical gems. I couldn't begin to list them all in this blog but I've aimed to summarise the stages of rehab. Be sure to read the original article for the finer detail.

Stage one: isometric loading

Isometric exercises have been proven to provide immediate pain relief in patella tendinopathy (Rio, Kidgell, Purdam et al., 2015).

- In phase one we use isometric exercises to control load and pain. Carefully monitor and alter load until the tendon settles within 24 hours of activity and pain can be assessed with the single leg decline squat.

- Pain can be 3/10 to begin with but don’t let it increase more than 5/10 during the exercises and the pain has to settle within 24 hours otherwise the load tolerance has been exceeded and the program needs to be modified.

- 5 x 45 isometric contractions at 70% MVC

- Best at 30-60 degrees of knee flexion.

- Knee extension can be done with a leg press.

- A good indication of if you’ve picked the right amount of load is an immediate reduction in pain post treatment.

- Other exercises that address other muscles and body regions should be commenced during the phase too.

You might be wondering how we can take this scientific study and translate it into in-season, in-training treatment if you don't have access to the equipment? Well I’ve done it with volleyball players and this is how it went.

Perform a single leg squat (no I didn’t have a decline squat board at the stadium so had to settle for a single leg squat) and measure pain. In sitting with the leg positioned 90 degrees flexion I lifted (passively) the knee to 60 degrees flexion and then asked the player to press against my hand to gain a sense of how much resistance they comfortably would push into my resistance. From there we aimed for 70% but I told them the aim is to keep the leg still and I would lift it up and down, not them. It’s a makeshift isometric treatment. We positioned the knee, together resisted a isometric contraction for 45 seconds and repeated this 5 times before reassessing single leg squat. It worked…. amazingly the player got enough pain relief to continue training in the backcourt (no jumping but squatting). The player was really excited to see that her knee pain could be modified and from there we began a more formal rehab program.

Stage two: isotonic loading

- This phase begins when the movements can be performed without pain increasing above 3/10.

- They will be done in both non weight bearing and weight bearing positions.

- To begin with keep the knee between 10-60 degrees of knee flexion and slowly progress towards 90 degrees knee flexion.

- The aim of isotonic loading is to restore muscle bulk and strength through functional range of movement.

- Movements are preferentially single leg based to specifically target control and balance.

- Exercises may include leg extensions, leg press, split squat or single leg squat.

- Aim to complete 3-4 sets of resistance that can be completed at 15RM and slowly progress towards 6RM.

- Stage 1 exercises are still completed on days off.

- Stage 2 exercises continue throughout the rest of the rehabilitation program.

Stage three: energy storage loading

- This phase is about reintroducing energy storage and restoring power.

- Malliaras et al (2015) suggest that when an athlete can perform 4-8 repetitions of a single leg press at 150% BW that they may try stage three exercises. But pain must be <3/10 and symptoms must settle within 24 hours.

- In this phase movements become more sport specific so you need to discuss with the athlete and coach about what the demands of their position are. How many times does a volleyball player need to jump during training? Hundreds of times I suspect.

- Exercises can vary from jumping, landing, changing direction, cutting, accelerating, decelerating and also vary in volume, frequency and intensity.

- Start with 3 sets of 8-10 repetitions of low intensity jumps and lands, split squat jumps, single leg hops, forward hops and they if you're treating a volleyball player, progress to spike jumps, block jumps, jump serves, landing and turning from jumps, landing and diving from jumps etc.

Stage four: Return to sport

- Return to training can be done when energy storage exercises are tolerated 3 times a week without aggravation and symptoms settle within 24 hours.

- Triple hop test and vertical jump are great tests to measure suitability for return to training.

- Slowly increase training to match the load and volume from stage three and progressively increase without increased tendon symptoms longer than 24 hours.

- Also take care not to have more than 3 high load trainings a week to allow for sufficient recovery time for the tendons.

- Allow for return to sport when full training is tolerated without increase in symptoms longer that 24 hours after training.

- One thing to be careful of is understanding the impact of fatigue on landing technique. Often we don’t do enough to fatigue clients during assessment and rehabilitation and we don’t see what compensation strategies they will adopt and they may not notice them either. It has been shown that when fatigued, people will land from a vertical jump with less knee flexion and more hip flexion (a stiffer leg) which is thought to be a protective mechanism to offload the patella tendon (Edwards, et al., 2014). But landing with a stiffer leg can lead to other injuries above and below the knee and should be identified and addressed.

Stage five: maintenance

Yes there is a stage 5. At least 2 days a week are the athletes performing exercises to maintain their flexibility? Are they performing strengthening exercises from stage 2 - single leg squat, single leg leg press, and knee extensions to maintain their strength? And if their pain reoccurs - are they using the isometric exercise to manage their pain? Maintenance is key to preventing re-aggravation and maintaining their function in the future.

Conclusion

Hopefully this blog outlines the phases of treatment that we can go through to treat patella tendinopathy. It's a tricky condition to manage and often we need to work really hard at the beginning to bring the tendon back under load tolerance and to reduce tendon pain. There is no quick fix and it's going to take time and hard work. After reading these studies I help empowered and inspired to work harder with my clients towards improving their knee pain, addressing biomechanical factors, retaining the entire kinetic chain and better educating them about their problem. The ultimate aim is to restore function and enable return to sport and this a great framework to help you achieve these goals.

Sian

References

Cook, J. L., Khan, K. M., Kiss, Z. S., Coleman, B. D., & Griffiths, L. (2001). Asymptomatic hypoechoic regions on patellar tendon ultrasound: A 4‐year clinical and ultrasound followup of 46 tendons. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 11(6), 321-327.

Edwards, S., Steele, J. R., Purdam, C. R., Cook, J. L., & McGhee, D. E. (2014). Alterations to landing technique and patellar tendon loading in response to fatigue. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 46(2), 330-340.

Malliaras, P., & Cook, J. (2006). Patellar tendons with normal imaging and pain: change in imaging and pain status over a volleyball season. Clinical journal of sport medicine, 16(5), 388-391.

Malliaras, P., Cook, J., Purdam, C., & Rio, E. (2015). Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, (0), 1-33.

Purdam, C. R., Jonsson, P., Alfredson, H., Lorentzon, R., Cook, J. L., & Khan, K. M. (2004). A pilot study of the eccentric decline squat in the management of painful chronic patellar tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine, 38(4), 395-397.

Rio, E., Kidgell, D., Moseley, G. L., & Cook, J. (2015a). Elevated corticospinal excitability in patellar tendinopathy compared with other anterior knee pain or no pain. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports.

Rio, E., Kidgell, D., Purdam, C., Gaida, J., Moseley, G. L., Pearce, A. J., & Cook, J. (2015b). Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine.

Rudavsky, A., & Cook, J. (2014). Physiotherapy management of patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee). Journal of physiotherapy, 60(3), 122-129.

van Ark, M., Cook, J., Docking, S., Zwerver, J., Gaida, J., van den Akker-Scheek, I., & Rio, E. (2014). 14 Exercise Programs To Decrease Pain In Athletes With Patellar Tendinopathy In-season: A Rct. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(Suppl 2), A9-A10.