Shoulder Multidirectional instability & surgical repair

I am glad to have this opportunity to share with you in this blog some of the skills and evidence that has been extraordinarily helpful to me in my management of a patient with multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder, and her recovery following multiple dislocations.

In this blog I will be giving you an introduction to the protocols that guided my clinical reasoning and treatment, discuss the key assessment findings that measured patient progress and describe the surgical management which ultimately lead to a very positive prognosis. The reason I wanted to write this blog was to reflect on the decision points which took place over the course of 12 months while working with my patient. More importantly, to capture in this story the resilience and optimism that lead to regaining excellent function of her right shoulder.

Ms C is someone who has lived with ligamentous laxity (HMS) her whole life, and despite multiple challenging musculoskeletal injuries, she has remained highly active and functional in her daily life. Throughout our 12 month journey, Ms C faced countless challenges and setbacks beyond the physical recovery of her shoulder injury; COVID, gastro, the flu, etc, all of which challenged her ability to stay committed to rehabilitation. Ultimately, surgery was the best option for Ms C, but this decision was finalised after months of structured goal-driven rehabilitation and very care consideration of the impact on her and her family’s life.

Our first consult was in early May 2023. Ms C had recently fallen onto an outstretched arm while mountain bike riding and sustained an acute anterior dislocation of her right shoulder. It was the third in 6 years, but the first to not spontaneously relocate. She walked 25 minutes to ED and had a relocation under analgesia.

Initial consultation:

Observation of resting posture: Resting scapula position was symmetrical with a small element of downward rotation and anterior tilt.

Observation of scapulohumeral rhythm: More prominent is the lack of scapula upward rotation during AROM of flexion

Active ROM: Flex and abd full range 140 degrees with pain at top associated with inf glide of GHJ (pain free with manual correct of GH into sup glide, pain free with scapula UR)

Apprehension/ instability: +ve apprehension test, pain reduces with gentle ant pressure. Pain and instability in passive ER and abd

Strength: Isometric strength Gr 4 pain free at 0 degrees elevation. Not able to assess in an elevated position due to pain and instability

Function: unable to sleep on the RHS and all overhead activities were uncomfortable and unstable

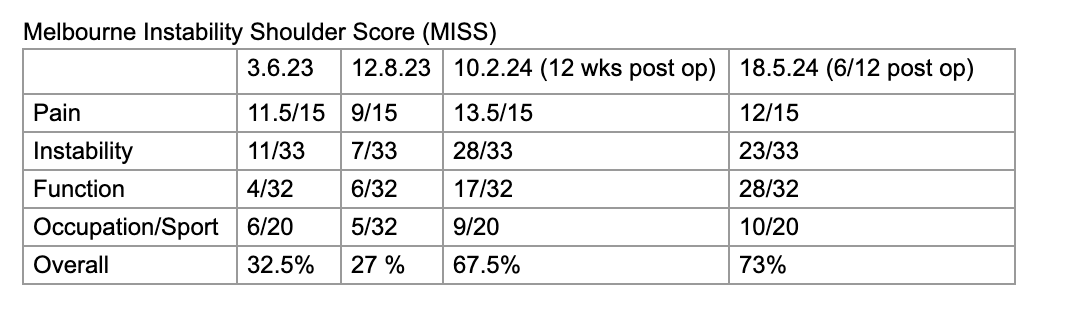

Outcome measure: MISS 32.5%

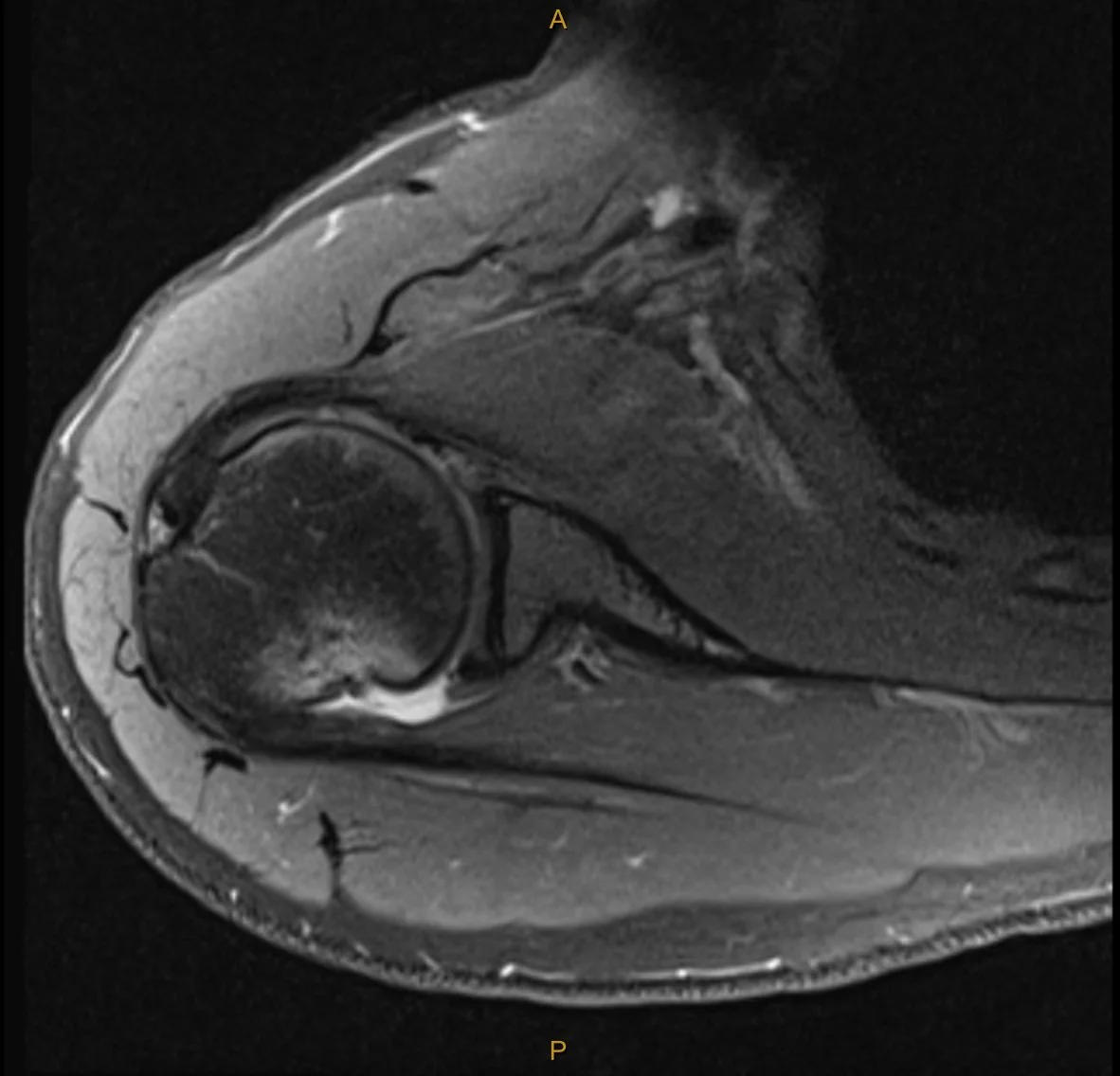

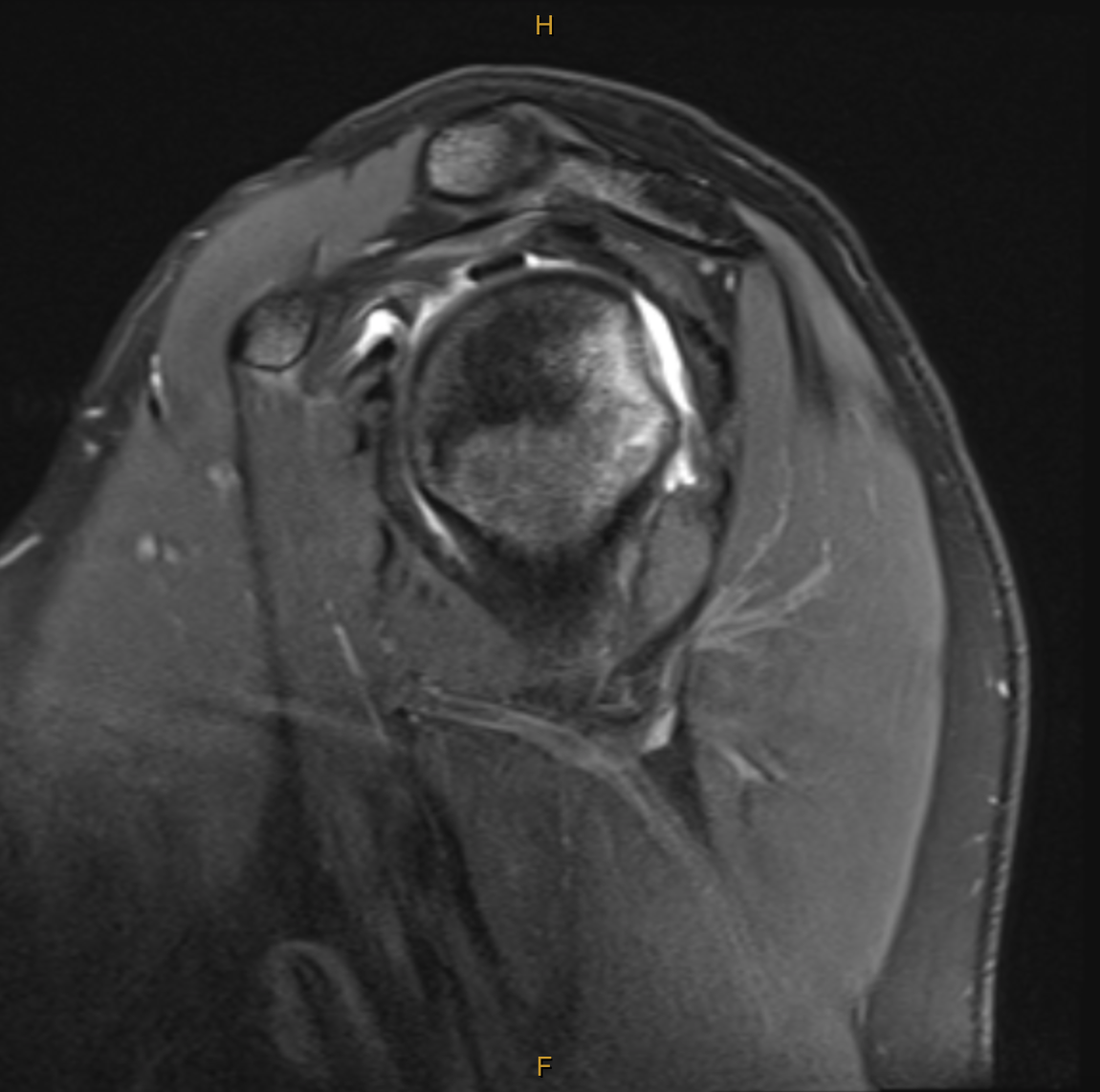

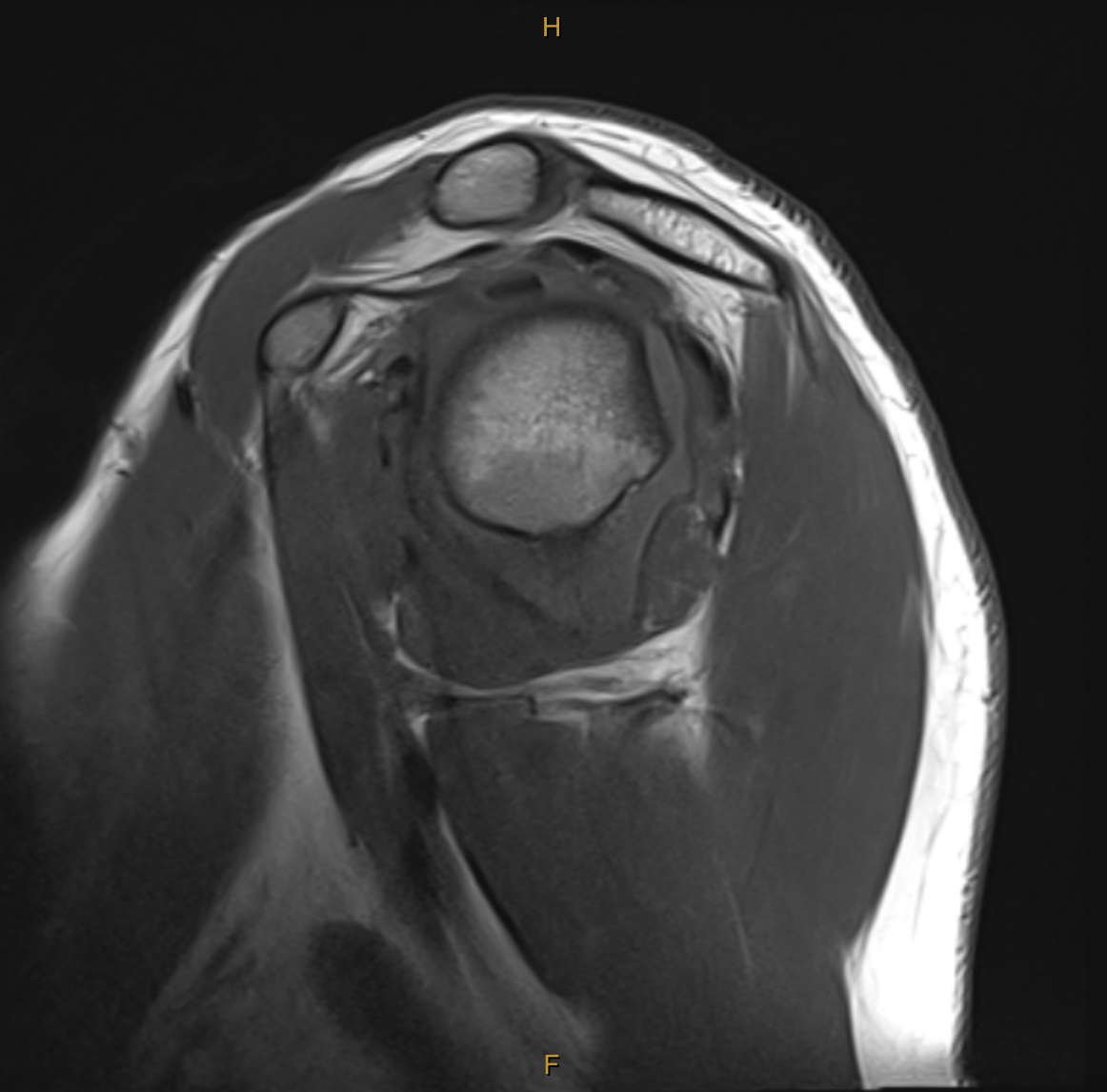

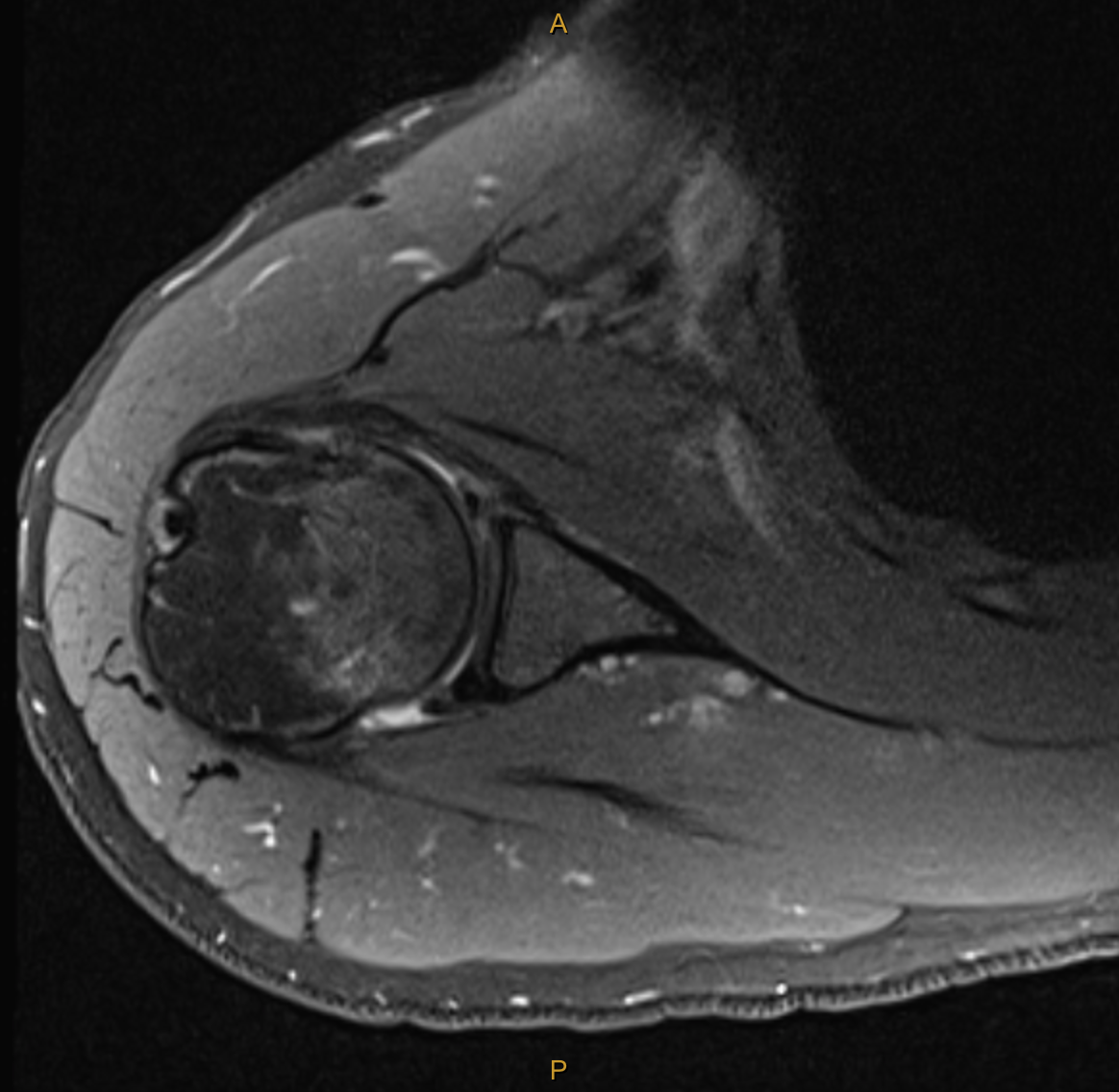

My clinical impression was the Ms C’s presentation was consistent with the event of an anterior dislocation and that MRI would best visualise the extent of tissue pathology. The report was incredibly detailed, and yet, there was additional structural damage which was not found until months later during surgery. The key findings (and my thoughts on their significance) are below:

Broad Hill-sachs lesion with underlying bone marrow oedema in keeping with recent anterior macroinstability event.

Impact fracture of the humeral head from contact on the glenoid. This fracture and indentation into the humeral head does not improve unless operated on and can lead to further instability and dislocation in positions of elevation and external rotation as the humeral head moves past the glenoid. This particular part of the injury is what is managed with the “remplissage” technique. (indication for surgery).

The bone marrow oedema can take between 3-6 months to settle (indication for wait and see).

Mild complex tear of the inferior to anterosuperior labrum extending from roughly the 6 o’clock position to the 10 o’clock position. [Fibrocartilaginous Bankart lesion]

No accompanying osseous Bankart lesion. [The glenoid was not fractured during dislocation]

There is slight elevation of the anterior glenolabral periosteum, consistent with some periosteal stripping.

No significant glenohumeral chondropathy.

Small joint effusion.

Intact cuff.

Not reported until surgery:Posterior labral tear and anteriorinferior chondral damage.

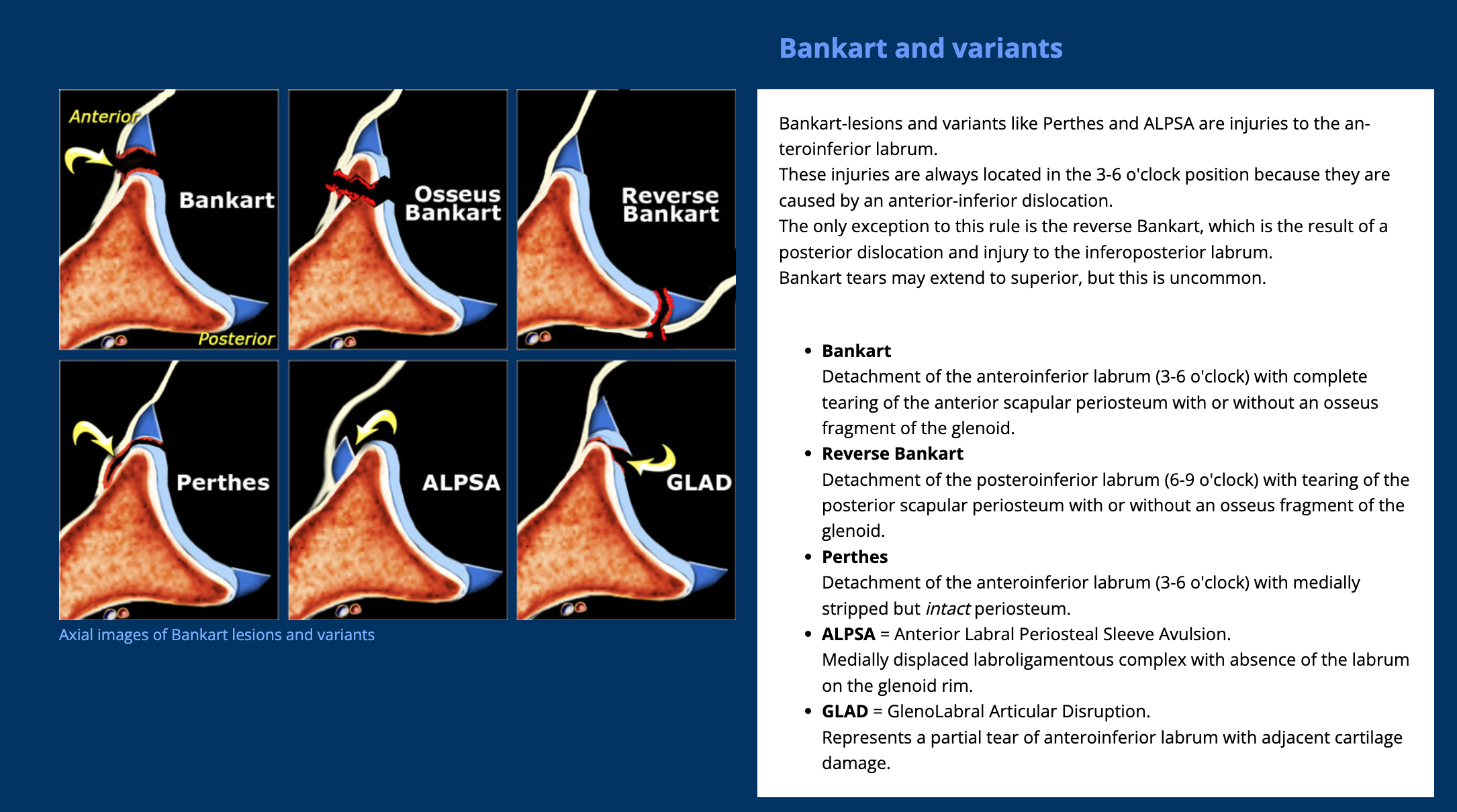

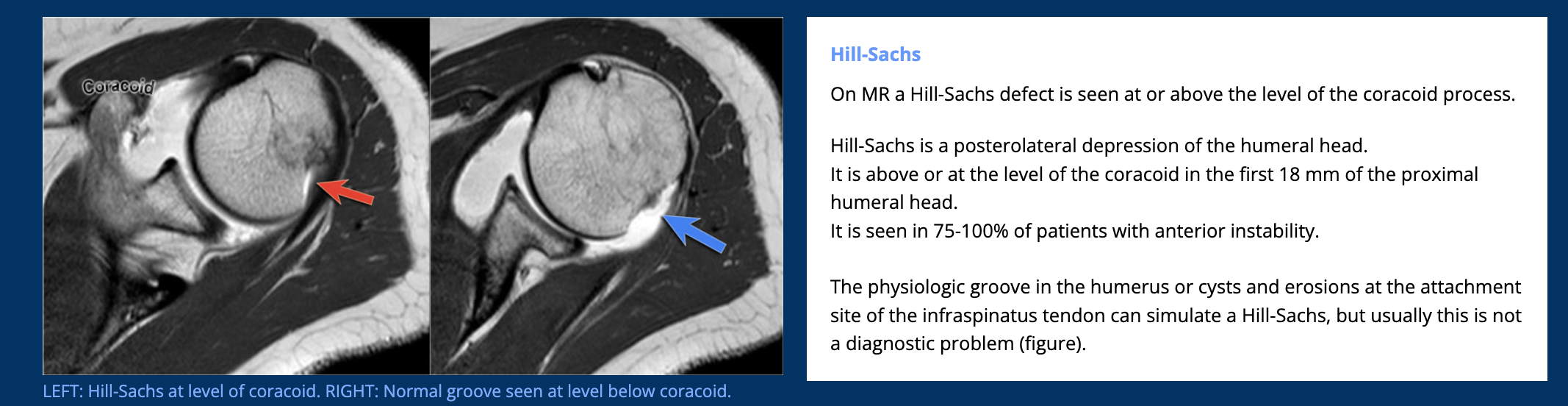

In addition to the exact MRI findings for this case, I have also added some images which outline the variants of a Bankart lesion and Hill-Sachs lesion below.

In 2023, two specialists presented at our in-house professional development. The first was presented by Dr. Sarah Warby, co-author of the Watson-Warby protocol for MDI. The second was Mr. Kemble Wang, a Melbourne-based Orthopedic surgeon of upper extremity conditions. Using the guidance provided by Dr. Warby, I chose to follow the Watson-Warby Protocol. I even shared this protocol with the patient so she could understand the phases, goals and the flow-chart for decision making around exercise prescription.

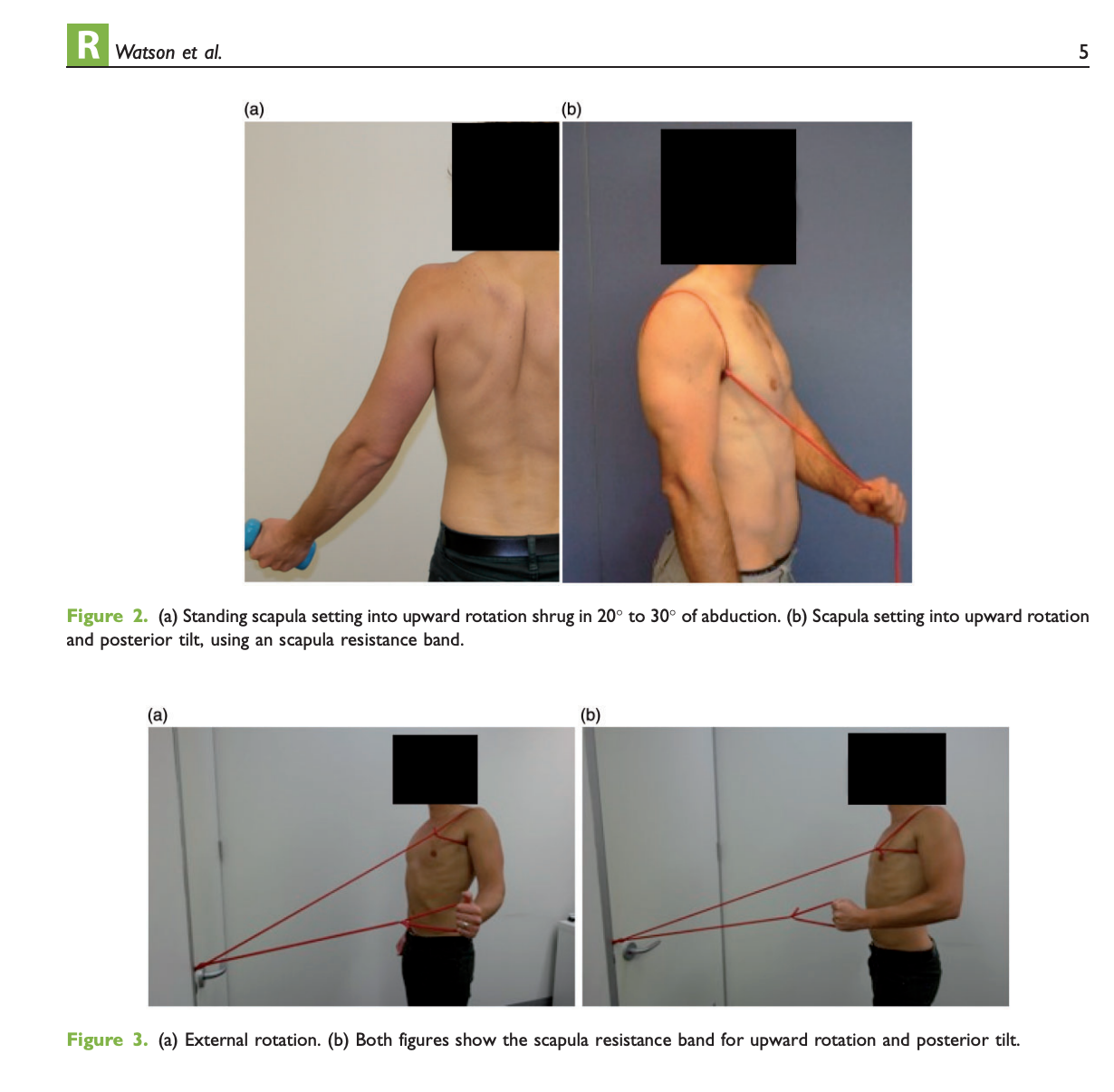

The MDI protocol places a strong emphasis on retraining scapula resting position as well as scapulohumeral rhythm during a variety of functional movements. As noted in the initial assessment, there were observable deficits in resting position and SHR during elevation, which changed with manual repositioning and therefore lead me to believe that following the MDI protocol was the most evidence-based approach for early rehabilitation.

(Watson, et al., 2016, p,5).

We began stage 1 of the MDI program in June:

Red theraband scapula setting posterior tilt and upward rotation

shrug 0kg 3 x 12 to start

short arc ext, bent elbow, to neutral 3 x 10

short arc external rotation, 3 x 10

In addition to following the prescription from the protocol, I also chose to use the Melbourne Shoulder Instability Index (MSII) as a primary outcome measure. Measurements were taken at baseline, 3 months and again 3 and 6 months post operative. The change in results was actually a little staggering and needed to be considered holistically with progress in strength and return of function. Let me explain this in more detail…

At first when the patient completed the outcome measure, she described herself as quite close to her normal baseline, with a score of 32.5%. I was shocked. Ms C was functioning through her life as mother of two school-aged children, and caring for her husband (recent lung cancer) and managing all her home ADLs with such a high degree of instability. The score dramatically changed post-operatively to 67.5% at 3 months post-op. I recall her LOF actually being quite low at this time (around 6 weeks out of the sling) and yet her sense of stability was so much higher. I think on reflection this shows me that functional levels and impairments do not correlate with sense of stability and documenting a range of outcome measures is beneficial in monitoring change and progress.

Having reviewed the MRI results and commencing the first phase of the MDI rehabilitation protocol, we also initiated a referral for specialist opinion. I chose to refer Ms C to Mr. Kemble Wang, a Melbourne-based orthopaedic surgeon of the upper limb. Kemble Wang has been such a fantastic surgeon to collaborate with. Easy to contact, considerate in his letters, wholistic in his care. I received a detailed letter after their first consultation documenting the following:

Right shoulder structural instability with labral tear, as well as MDI with loose ligaments/capsular structures.

Beighton score for ligamentous instability 9/9

Full ROM

Positive Gagey sign bilateral

Anterior and posterior apprehension

Increased humeral head translation anteriorly and posteriorly

Mr Wang also provided his opinions around considerations for surgery. The first was about reducing the risk of further dislocation. He noted that without surgery her chance of further dislocation is 90-95%. With surgery 15-20%. The second consideration was around achieving baseline MDI discomfort. Mr Wang noted that it may take several months of conservative therapy to reach baseline. If the shoulder does not return to baseline and is impacting day-to-day activity then surgery should be considered. Kemble monitored Ms C’s progress over 3-5 months and kept assuring her that “You are not missing out on anything by waiting.”

Up to this point in the blog, I have outlined a 2-part initial management of structured conservative care and early referral for specialist opinion. Let’s briefly look now at the progress over 3-6 months of conservative care. We continued to progress through the Warby-Watson MDI program with Ms C showing improvements in her resting and active scapula positioning. All together, we continued rehab exercises for 6 months, It was evident from about 3 months however, that the following impairments were preventing Ms C from reaching baseline.

Soreness in the shoulder, particularly at night impairing sleep.

Instability symptoms of numbness and neural pain into the arm with sustained positions.

Persistent weakness (despite correction in scapular stability and scapulohumeral rhythm in upward rotation). Using the ActivForce we calculated a 60-66% difference in strength of shoulder ER and flexion. The ActivForce was really revealing and highlighted how MMT alone don’t always measure imbalances.

Limited HBB range with the R side being Sacral and L T4.

Over the course of 6 months and despite progressing through the MDI protocol, we did not reach an acceptable baseline. This extended conservation timeframe did allow us to have multiple conversations about surgery and carefully plan our a recovery path and plan social support. Some of the questions addressed were:

What would surgery do to improve her quality of life and daily function?

What does the surgery involved and how long is the period of sling wearing?

During this time, how does Ms C and her family cope with meals, home ADLs, school drop offs and pick ups and so much more?

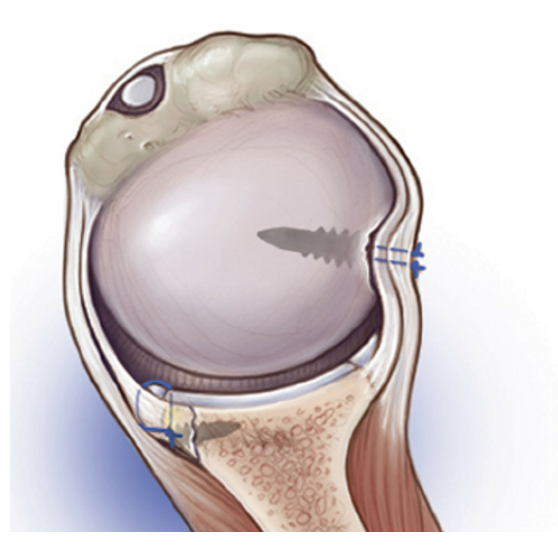

By November, Ms C was prepared and ready. The surgery involved a Right Bankart repair with “knotless” Remplissage. The image below is provided by Mr Wang in the patient-information with the following explanation of the procedure.

(https://www.kemblewang.com/bankart-remplissage)

“The Bankart repair refers to repair of the labral tear, and the Remplissage procedure refers to filling up of the divot with soft tissue (like filling in a pothole on the road). Whilst the Bankart repair is the mainstay of the procedure, Kemble sometimes adds a remplissage to improve stability, especially in young/adolescent patients. The following is a schematic diagram of such a procedure.”

Here is an additiona link to a video of the surgical techniques used.

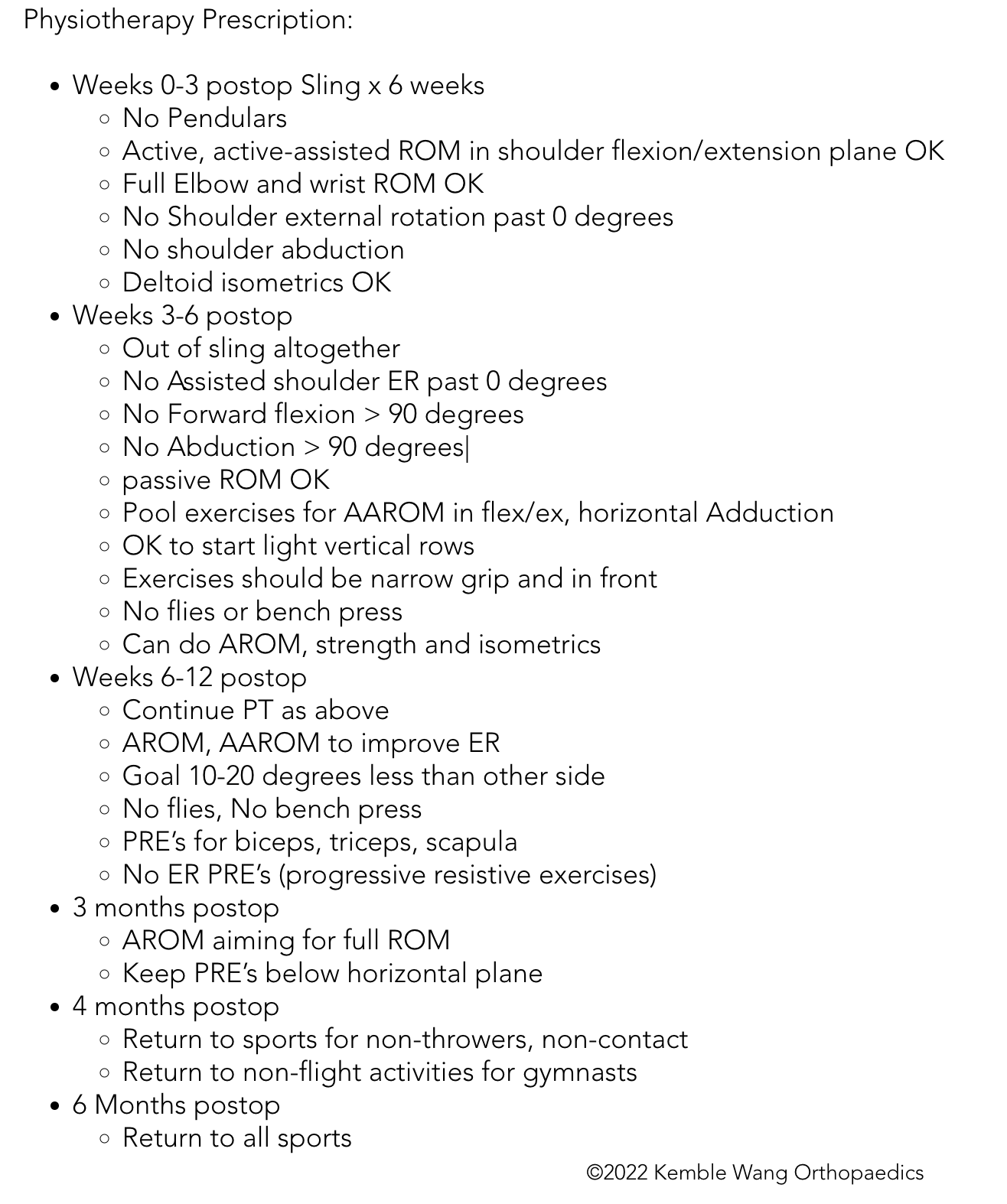

Mr Wang also provides patients with a home-based rehab protocol for the first 6 weeks. I have added this below.

Taken in february 6th (11 weeks post operative and 5 weeks out of sling) and demonstrating wasting along the medial border of the scapula, upper trapezius and infraspinatus (widespread disuse atrophy).

Our first post-operative assessment was at 6 weeks when Ms C stopped wearing the sling. What I want to mention was that even though the protocol states no ER >0, Flex > 90 and Abd > 90, the patient presented with ROM far less than these limits. Both myself and Mr Wang were immediately concerned about a capsular restriction impacting her recovery.

Our initial assessment noted:

Active flexion limited to 50 degrees, active assisted flexion limited to 70 degrees.

External rotation to 0 degrees achieved.

Global disuse atrophy. This loss of muscle bulk is always a little disheartening.

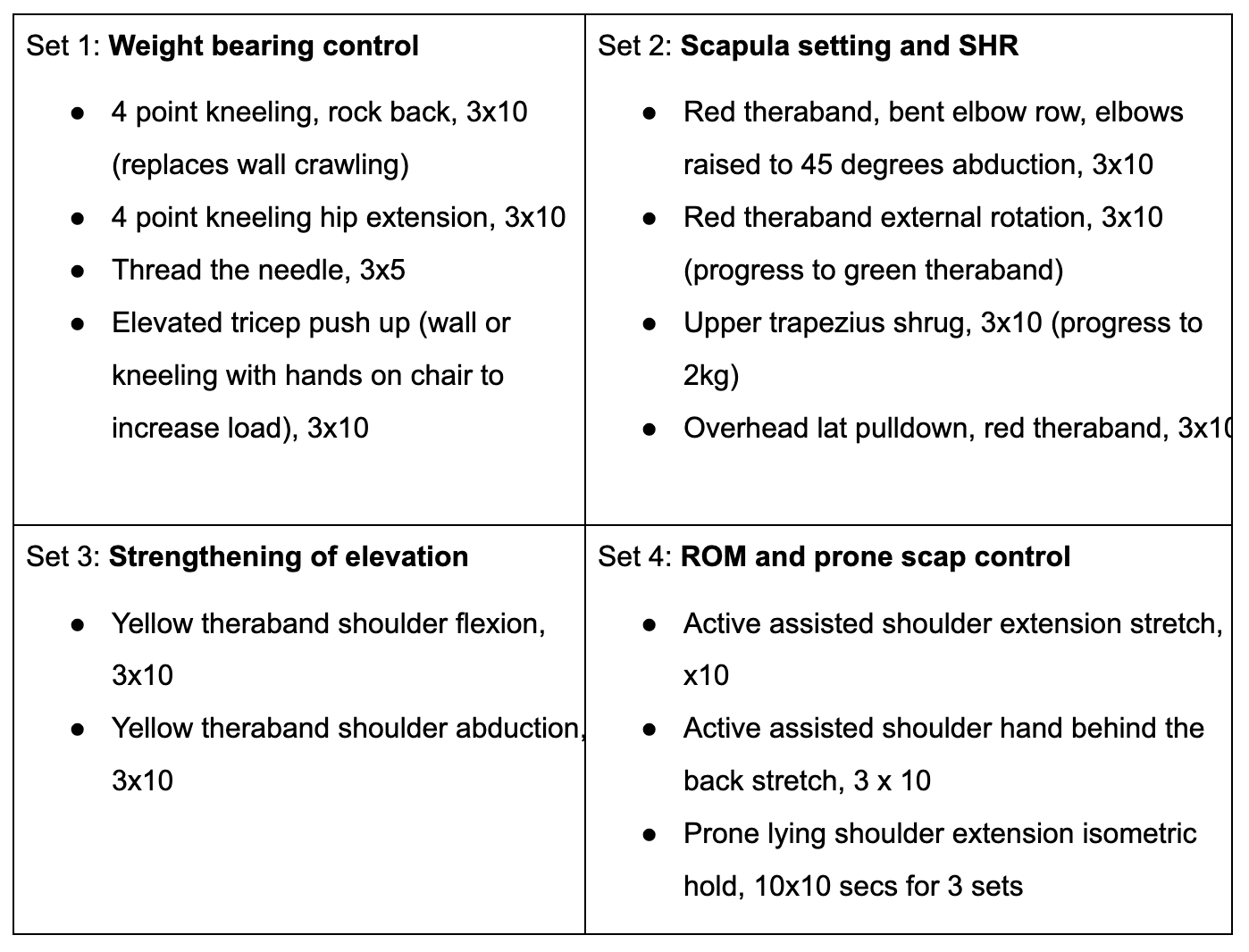

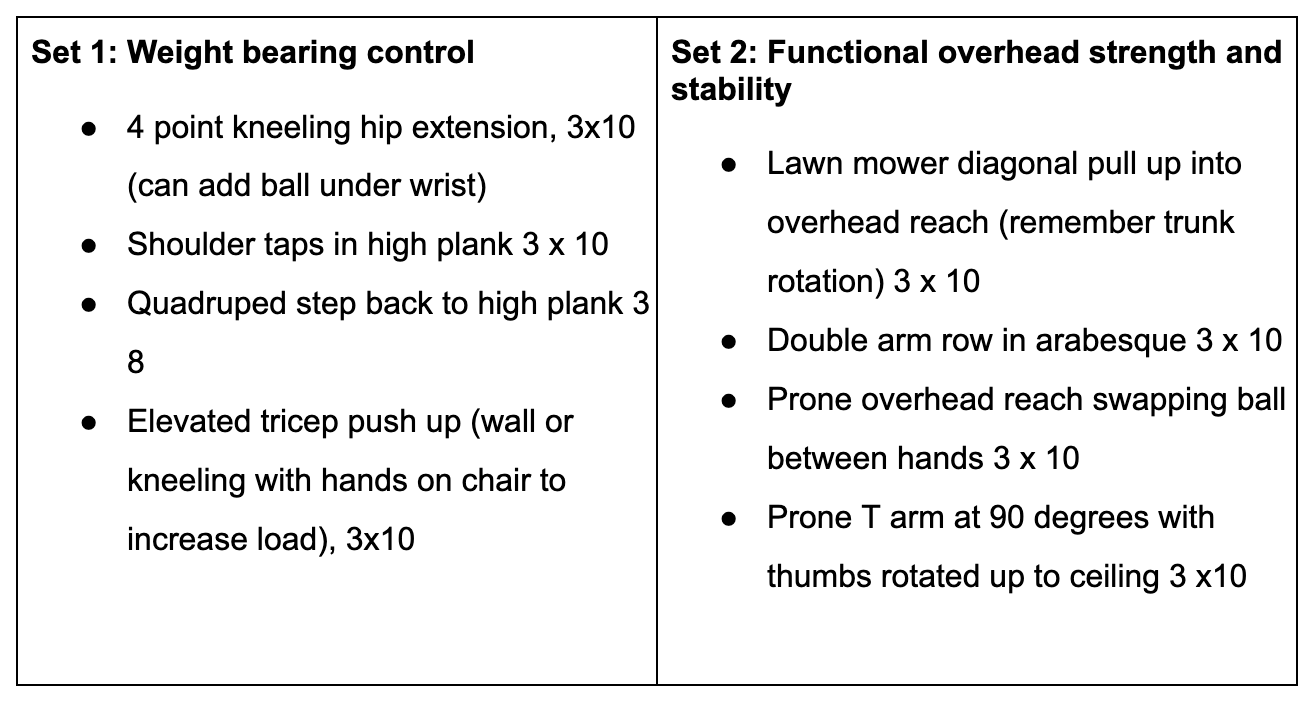

Immediately Ms C began daily rehab of her range of movement and there was a steady improvement, yet continued to follow a capsular stiffness pattern at end of range. At 3 months post op repeated another detailed reassessment including the MSII. Her values had increased to 67%. Ms C was sleeping well and no longer impaired by pain. Instability was not reported and we had been able to commence some weight bearing exercises. Hand behind back range was improving (very pleasing for both the patient and myself). When constructing her home exercise program, I kept in mind the following goals: weight bearing control, overall range of motion, reintroducing scapular control from the MDI protocol, strengthening in higher ranges of elevation and prone scapular control.

At the 5 month review, we photographed 2 points of abduction AROM. What is interesting to me is:

Her scapular positioning at 90 degrees abduction and overhead reach.

That although her abduction measures 150deg with a goniometer, her functional reach is still sufficient. Relating this back to Mr Wang’s protocol which states “goal for ROM is 10-20 deg less the other side”, because the left hand side is hypermobile, we may not want to chase this goal. In fact, you can see the humeral head dropping inferiorly in this photo (LHS). Here is one example of how we constantly needed to consider what our goals for recovery were for this patient.

Around 5 months, I have highlighted the following in my assessment:

Function: hanging washing on the line, road riding, moving the lawn.

ROM: HBB improving (T8)

No episodes of instability

Strength: ER and flexion both improving, Gr 4+/5

6 months post operative

In preparation for her 6 month surgical follow-up, we performed a battery of tests to evaluate progress across multiple domains.

Functionally, the patient was managing her ADLS without difficulty and becoming more involved in the garden (lawn mowing, edge trimming, digging, lifting wheelbarrows). She had noticed that her strength and endurance with holding her arm raised above shoulder height was impaired and fatigued quickly compared to the left hand side.

Strength assessment (using ActivForce):

External rotation was reduced by 25% compared to the LHS.

Internal rotation was reduced by 15% compared to the LHS.

Flexion at 90 degrees was reduced by 48% compared to the LHS.

Despite a huge change in her sense of stability (MSII 73%) her flexion strength in elevated ranges was almost 1/2 of her LHS. Structurally, healing is going really well, physically, there is a lot more rehabilitation to reduce this asymmetry in strength.

Range of motion (as per previous assessments) - functional overhead reach and HBB to mid scapula range.

Return to sport: the patient had commenced stationary riding on her mountain bike in an indoor setting using a trainer, and road riding. Our future goals are to develop a more structured plan around returning to mountain bike riding while keeping in mind the risks associated with falling and potential future dislocations on either side.

Conclusion:

Reflecting on the past 12 months working with Ms C, I am so thankful to have had the opportunity to go on this journey. As a clinician, these are the cases that bring me so much joy and excitement to show up to work and help patients with their recovery. Ms C has been committed to her physiotherapy treatment plan, positive despite hardship, confident in our therapeutic alliance and generous with the gift of time.

The first 6 months allowed us to delve deeply into the nuances of the Watson-Warby protocol and explore the exerices in each phase. This resulted in a much deeper understanding of the application of the protocol that can’t be fully grasped by just reading it. MDI and HMS are challenging conditions to manage, and in this case, there were additional factors which altered our treatment plan through it’s course. The first was that motor control impairments, strength deficits (as measured on the ActivForce) and functional stability (MSII) don’t always improve in a linear progression. For Ms C, her symptoms plateau before an acceptable baseline was reached. Clinically, the ActivForce was critical in identifying to both myself and the patient the asymmetries present. The second factor was finding out during the surgery that there was additional structural damage inhibiting recovery which was not visualized on the MRI. I am really impressed by the care offered by Kemble Wang and enjoyed partnering closely with him to assist with decision making. This lead to having a patient who thoughtfully prepared for surgery and was committed to the ongoing long-term rehab required post-operatively. It feels like the perfect balance between evidence-informed, patient-centre, goal-driven care. I’m left feeling hopeful and excited to work with my next patient who might benefit from this treatment approach.

Sian

references

Watson, L., Warby, S., Balster, S., Lenssen, R., & Pizzari, T. (2016). The treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder with a rehabilitation program: Part 1. Shoulder & elbow, 8(4), 271-278.

Warby, S. A., Pizzari, T., Ford, J. J., Hahne, A. J., & Watson, L. (2016). Exercise-based management versus surgery for multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine, 50(18), 1115-1123.

Warby, S. A., Ford, J. J., Hahne, A. J., Watson, L., Balster, S., Lenssen, R., & Pizzari, T. (2016). Effect of exercise-based management on multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: a pilot randomised controlled trial protocol. BMJ open, 6(9), e013083.

Watson, L., Warby, S., Balster, S., Lenssen, R., & Pizzari, T. (2017). The treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder with a rehabilitation programme: Part 2. Shoulder & elbow, 9(1), 46-53.

https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Beighton-Score-2017.pdf

https://www.physio-pedia.com/Beighton_score

https://radiologyassistant.nl/musculoskeletal/shoulder/instability#bankart-and-variants-bankart-lesion

https://www.arthrex.com/search?q=bankart%20repair

https://www.kemblewang.com/

https://www.kemblewang.com/bankart-remplissage

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8010490_A_new_clinical_outcome_measure_of_glenohumeral_joint_instability_The_MISS_questionnaire