Ankle Syndesmosis Injuries - Management

In 2017, Alicia published two great blogs on the anatomy of the ankle syndesmosis and assessment of injuries to this body region. Recently I listened to two podcasts by Clinical Edge with guest speaker Chris Morgan (on assessment and management), which has motivated me to continue our final blog on the management strategies for ankle syndesmosis injuries.

The first podcast covers assessment of injury severity. Unlike other ankle injuries, swelling and pain are not as reliable in indicating the severity of injury. As Alicia discussed in the first blog, injury is often traumatic forcing the joint into hyper-dorsiflexion and external rotation. Morgan et al (2014, p. 602) report that “a large proportion of match related ankle injuries (40%) are due to foul play”. Morgan expands further on this topic during the podcast, reinforcing the importance of understanding the mechanism of injury (MOI) to assist with early diagnosis and classification of injury severity, with the goal of appropriately managing the injured tissues.

Conservative management

Protect the injury

“Delayed diagnosis is associated with prolonged return to play and poor outcomes emphasizing the importance of early detection” (Latham et al., 2017, p.4). The biggest challenge for treatment is early detection!

Why is early detection and protection so important to recovery?

The ankle syndesmosis provides stability to the ankle joint, particularly the mortice. Ankle dorsiflexion is a vital movement for functional recovery of the ankle joint, but it is also the movement that caused the tissues to become injured. Therefore, it is important to protect the joint while these tissues are healing, this is achieved through a period of altered weight bearing in a boot (Latham, et al, 2017). I was actually a little surprised to hear Morgan discuss the timeframes for each stage of recovery and specifically this first stage of altered weight bearing as only lasting a few days. Latham et al (2017) discuss the differences between conservative management and surgical management timeframes of the length of non-weight bearing (which is ultimately guided by the surgeon and their operative technique).

My expectation was that healing timeframes would be longer, but as Morgan mentions, if you detect them early and protect them well, recovery can be quite fast for a grade 1 injury. Athletes can return to play within 8 days (Morgan et al., 2014). This was so encouraging to hear in the podcast and the outline of rehabilitation is presented for each grade of injury in his paper in 2014. While a short period of immobilisation is more beneficial for the patient, if they are still in pain on walking, additional time in the boot should be applied, to prevent further aggravation of the tissue. So while players can return in a week, immobilisation should continue until the player is pain-free at rest and on walking.

Another interesting point raised by Morgan in the podcast was about letting the tissues rest. Once the diagnosis is suspected, stop poking the tissues. The tests themselves stress the injured tissues and do not need to be repeated every day to mark progress. Let the ankle rest in the boot. For grade 1 injuries, this period of immobilization is likely to last 1-2 days, for grade 2 injuries you may wish to protect the joint by not moving past neutral dorsiflexion ROM for up to 10 days, and for grade 3 injuries, up to 4 weeks (Morgan et al., 2014, p. 608).

If dorsiflexion is particularly aggravating, a heel lift can be added into the boot, to completely offload the anterior structures and allow better healing through that syndesmosis region. Again, reduce the irritation of the tissue and it will heal quicker.

Strength & Conditioning

A maintenance strength and conditioning program is vital to prevent deconditioning during the period of immobilization. Remember that dorsiflexion is the movement we are wanting to protect, leaving a lot of other safe exercises available for patients to complete to prevent deconditioning.

Calf strength & ankle alignment:

Begin with a double leg calf raise. Your focus is on ankle alignment and prevention of rolling outwards (avoid supination/inversion).

Variations include back facing the wall, a wall squat with double leg calf raise, or squatting at the top of the double leg calf raise.

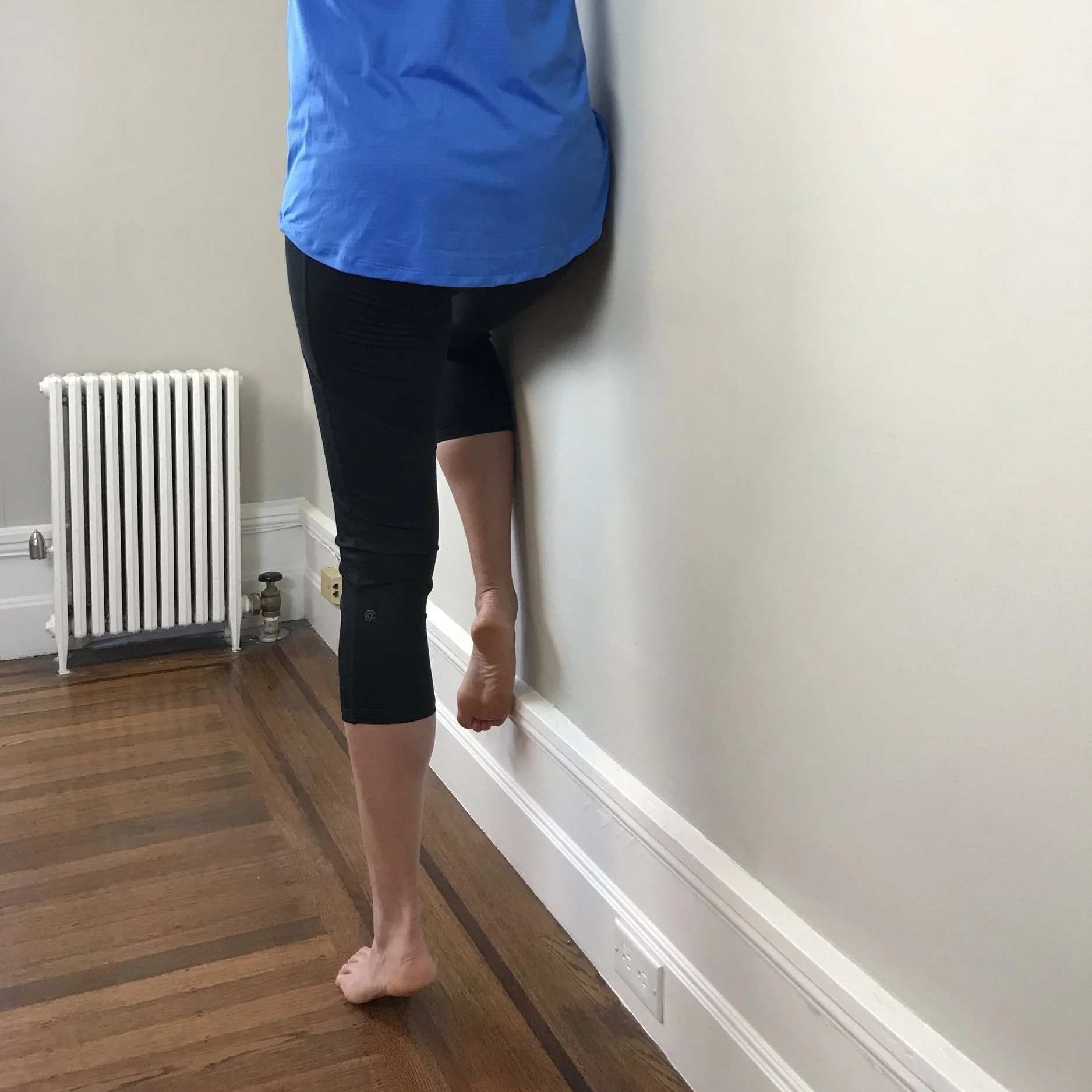

Progressions include single leg calf raise, side facing single leg calf raise with hand on the wall (to target balance), and side facing single leg calf raise with hip on the wall (to target hip strength).

Once you can complete a single leg calf raise you can progress to a single leg squat with calf raise to target quadricep strength and soleus control. This movement pattern is especially important to control the forces of landing.

Once movement patterns are strong and controlled, you may wish to do some more functional drills like walking on toes, slow jogging on toes, skipping on toes and hopping. All of these focus on balance and strength without loading ankle dorsiflexion ROM.

It is becoming more common for physiotherapists to use ‘protocol-based’ rehabilitation principles over ‘time-based’ as it allows for a more patient-centered approach. Within this approach for this specific injury, calf function test and knee to wall ankle dorsiflexion range are two key objective measures of progress.

Dorsiflexion is a measure of the joints ability to move and load the injured, while calf function (gastric and soleus) tells us about loading capacity of the joint and absorption of forces.

Calf function should be within 10% of the other side

Knee to wall should be within 15-20% of the other side

Other performance measures could be single leg hop for distance, triple hop test, star balance excursion tests – or other commonly used lower limb tests for return to sport assessment.

Chris Morgan discusses in his podcast using Alter G (a treadmill with additional air assistance reducing gravity) for early return to running at 50% body weight, which is discussed in further detail in the paper by Latham et al (2017).

Alicia has done a great job of capturing a range of exercise progressions to strengthen the kinetic chain and promote optional biomechanics. These are just some ideas to help you get creative in strength and conditioning without loaded dorsiflexion at the ankle. Make you rehabilitation patient-specific, sport-specific and fun! Each patient will have different sport requirements for return to play.

Return to sport (Calder et al., 2016; Latham et al., 2017; Sman et al., 2015):

As we prepare patients for return to sport, we need to provide them with rehabilitation exercises that progress them towards these test demands. That way, when the assessment time comes, the patient is prepared to pass. Readiness for running is commonly assessed with the single leg hop test for this injury (Sman et al., 2015) but even before that, you can ask the patient how confident they feel to hop on one leg. If there is any apprehension about joint stability, the patient will be hesitant to even try.

Many articles discuss that ankle syndesmosis injuries are associated with high levels of disability and delayed return to sport compared to lateral ligament ankle injuries and the reason being that they aren’t detected early enough (Latham et al., 2017). If detected and managed early, recovery can actually be quite accelerated.

Grade 1 = 2-3 weeks

Grade 2 stable = 45 days

Grade 2 unstable = 65 days

What about surgery?

Calder et al (2016) suggest that patients with a complete disruption of the syndesmosis require surgery. “Dynamic instability may require stabilization to prevent late adverse sequelae” (Calder et al, 2016., p. 635). These authors conducted a study looking purely at grade 2 injuries to determine if our clinical tests and radiological findings can predict return to sport timeframes and joint stability. The results were compared to the current diagnostic gold standard of joint arthroscopy (Sman et al., 2015). What they found is that the mean time frame for return to sport for a stable grade 2 was 45 days (23-63) and 65 days (27-104) for an unstable grade 2 injury. There was a direct association between RTS timeframes and length of time of immobilization (Calder et al., 2016, p.637).

“The most important finding of this study was that most patients with AITFL and deltoid ligament tenderness together with a positive squeeze test and external rotation test were found to have an unstable syndesmosis at arthroscope” (Calder et al., 2016, p.638). Physiotherapists can be confident in the meaning of the clinical tests if a thorough examination is performed in identifying more severe injuries early after injury. A combination of tests is advised for the best diagnostic accuracy – dorsiflexion and external rotation test, local tenderness of the syndesmosis ligaments, squeeze test, and dorsiflexion lunge with compression (Sman et al., 2015). Also, “if a patient is unable to perform a single leg hop, the injury may involve the ankle syndesmosis and specific signs/symptoms are recommended to confirm this, such as pain out of proportion to the apparent injury or pain felt up the shank or in the knee” (Sman et al., 2015, p. 6)

In researching syndesmosis injuries, I have realised how common they are, and how the previous “standard ankle treatment” of knee to wall stretching, ankle eversion strengthening and joint mobilisation into dorsiflexion actually aggravates and delays healing. Recognising these injuries early, with subjective features of anterior pain, pain on dorsiflexion and a MOI of dorsiflexion, then treating with the above-mentioned management, has drastically improved my treatment of ankle injuries. Treating the patient’s presenting complaint, rather than a cookie-cutter ankle treatment, has given the patient a much better prognosis and outcome.

Sian & Alicia

References:

Calder, J. D., Bamford, R., Petrie, A., & McCollum, G. A. (2016). Stable versus unstable grade II high ankle sprains: a prospective study predicting the need for surgical stabilization and time to return to sports. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 32(4), 634-642.

Latham, A. J., Goodwin, P. C., Stirling, B., & Budgen, A. (2017). Ankle syndesmosis repair and rehabilitation in professional rugby league players: a case series report. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine, 3(1), e000175.

Morgan, C., Konopinski, M., & Dunn, A. (2014). Conservative management of syndesmosis injuries in elite football. Sports Medicine Journal, 602-613.

Sikka, R. S., Fetzer, G. B., Sugarman, E., Wright, R. W., Fritts, H., Boyd, J. L., & Fischer, D. A. (2012). Correlating MRI findings with disability in syndesmotic sprains of NFL players. Foot & ankle international, 33(5), 371-378.

Sman, A. D., Hiller, C. E., Rae, K., Linklater, J., Black, D. A., Nicholson, L. L., ... & Refshauge, K. M. (2015). Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for ankle syndesmosis injury. Br J Sports Med, 49(5), 323-329.