Hip: Athletic Groin Pain Part 1

Athletic groin pain (AGP) is an umbrella term encompassing many causes of pain in the anterior hip and groin region. It is such a large umbrella that I wanted to look more closely at which conditions come under AGP. Luckily for us, Andy Franklyn-Miller and his team in Dublin have published many research papers on this topic, three of which I have found very helpful clinically and want to share with you.

AGP pain is most common in athletes participating in multidirectional sports such as soccer, Australian rules football (AFL), gaelic football, ice hockey and rugby union (Falvey, Kind, Kinsella & Franklyn-Miller., 2015). Among these sports, it is the 3rd to 4th most common sporting injury, however the morbidity rates of time away from sport are closer to that of fractures or joint reconstruction (Falvey, Franklyn-Miller & McCrory., 2008). It is therefore paramount that we spend time trying to understand how and why AGP occurs.

The fantastic thing about this research from Dublin is how they have looked at defining what the 'groin' is, what pathoanatomy can occur, how biomechanics comes into the picture, and where future research needs to be directed. This helped improved my knowledge base, encouraging me to think critically and analytically about patients with AGP, before jumping straight to treatment. Someone once described the groin triangle as the Bermuda triangle because it's easy to get lost with this patient group, and for a long time I felt that way.

This blog aims to clarify a few key points from three great articles (see references below), which I would strongly suggest reading for further detail on this topic.

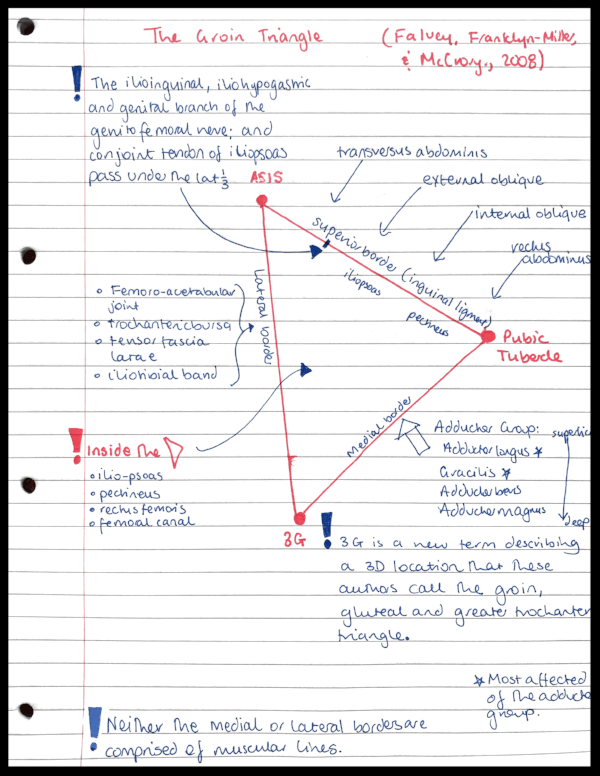

The Groin Triangle. Image source Google Images

What is the Groin Triangle?

To understand where athletic groin pain comes from, we need to know where it is. Falvey, Franklyn-Miller & McCrory published a paper in 2008, which is the best I've read to help understand the clinical anatomy of the groin.

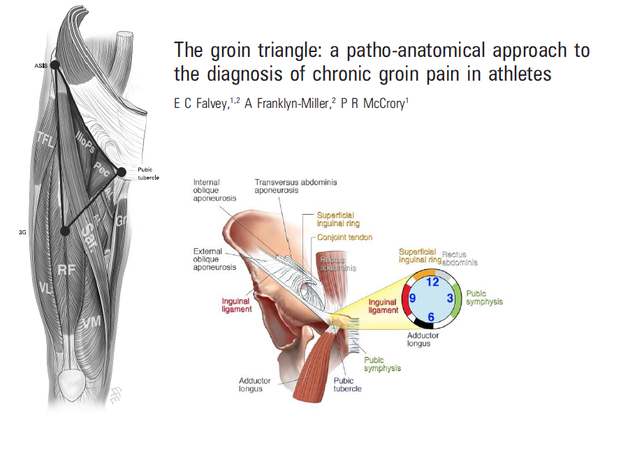

AGP is described as pain within the groin triangle. This triangle is defined by three apexes: the ASIS, the pubic tubercle and the 3G which is a point in space not a landmark. As you might see from the image below there are many muscles and structures which form each triangle border. In their 2008 paper Favey, Franklyn-Miller & McCrory discuss each anatomical region of the triangle, describe the structures that create that region and therefore the different pathologies related to different areas of the triangle. What you will notice from the two pictures below is that AGP encompasses many different pathologies, so remember that groin pain doesn't just mean pubic pain.

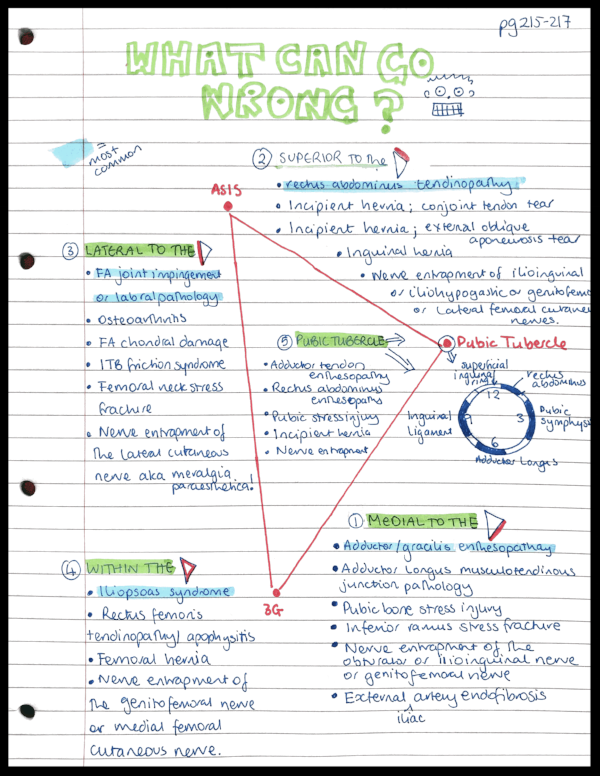

WHAT CAN GO WRONG?

After looking closely at the construction of this triangle, let's look at the possible anatomical pathologies. Each of these were described in detail in the original paper and also included associated clinical signs and physical tests.

The groin triangle and clock face of the pubic tubercle - image source Google Images

That is one long list! You can begin to appreciate how extensive the term "athletic groin pain" is and why knowing the anatomy is so important in guiding palpation and diagnosis. You might also be scratching your head wondering how one would manage all of these different problems? Even though there are many possible structural, anatomical and physiological reasons for developing groin pain, as therapists we need to avoid being overwhelmed by this list and instead focus on the underlying biomechanical faults that have lead to the pain developing through failed tissue loading. Let's take a look now at the 2-part article series on clinical assessment and diagnosis of AGP. What I think you see is that we are now moving away from a structural label and focussing on specific biomechanics. The authors emphasise this point by saying that a one size fits all approach is just not going to be effective (Franklyn-Miller, et al., 2016).

Part 1 - how well does our clinical examination correlate with MRI findings?

Clinical tests

In part 1, Falvey et al (2015) discuss the aspects of clinical examination that they used to diagnose AGP and how the clinical diagnosis relates to MRI reports. Their physical examination (which appears to be very thorough) included the following:

- Hip flexion, internal rotation and external rotation range of movement.

- Hip provocation tests of FADIR and FABER.

- Adductor squeeze test at 0, 45 and 90 degrees of hip flexion (called SQ0 | SQ45 | SQ90).

- Cross over test

- Prone hip internal and external rotation, Gaenslen's test and hip extension.

- Slump test and femoral slump test.

- Thomas and modified Thomas test.

- And the most helpful.....Palpation!

This examination includes: range of movement, pain provocation, muscle length and clearing tests for the SIJ, lumbar spine and neural tissues. What is doesn't include is manual muscle testing or functional performance tests. The reason being that they were most interested in the clinical tests that might correlate with Medical Imaging. Some tests help us make a diagnosis and others help us to determine where rehabilitation begins and the goals for exercise rehab.

Take a moment to reflect on what else you might include in your assessment, what functional performance tests you use, why, and what information you are taking from them.

Clinical diagnosis

From the assessment above participants were given one of the following diagnoses:

- Pubic aponeurosis injury

- Adductor injury

- Hip joint injury

- Hip flexor injury

- Inguinal injury

And just to point out, if you look at the construction of the triangle above, you will see that these are the most common injuries for each region of the triangle i.e above, medial, lateral, and within.

Personally, I look at this clinical assessment and am impressed by how thorough and well rounded it is. It highlights me to that there is no quick way to assess AGP and that assessment takes time. It also emphasises that symptoms do matter, clarification of where pain is felt is important, and confirming pain location through palpation and clinical tests helps us to narrow down AGP to the five categories above.

Outcome measures

The Copenhagen hip and groin score (HAGOS) is a validated outcome measure for this patient population. You can find the users guide here. It is a six subset scale that asks questions about

- Pain.

- Stiffness during the morning or later in the day.

- Symptoms such as clicking, noises, pain with stretching, pain with striding, and stabbing sensations.

- Limitations in physical movements such as bending/extending the hip, going up/down stairs, lying in bed at night, sitting, standing, and walking on hard or uneven surfaces.

- Limitations in daily activities such as bending over, picking something up, getting in and out of bed, and getting in and out of a car.

- Limitations in recreational activities and function such as squatting, running, pivoting, changing direction, and explosive movements.

- Restrictions on level of participation and quality of life.

This outcome measure questions many common aspects of groin pain that patients might describe about how they feel or how it is effecting their life. Even if you don't choose to use it, these questions are a great foundations for building out your subjective examination of a patient with AGP.

What did they find?

This was a reasonably large study, with 382 participants who had suffered from groin pain for a median time of 36 weeks. 36 weeks... thats a median time of 9 months! From this study, the authors were able to produce the data below expanding on our knowledge of AGP:

- Pain presentation: 42.7% had left sided GP, 38.2% had right sided GP, and 19.1% reported pain bilaterally (Falvey, et al., 2015, p. 3).

- Palpation findings (Falvey, et al., 2015, p. 3-4).:

- ~60% of cases were tender on palpation (TOP) over the adductor origin.

- ~67% were TOP over the pubic aponeurosis i.e more were painful above the pubic tubercle than below!

- 2.6% were TOP over the superficial inguinal ring.

- Range of movement (Falvey, et al., 2015, p. 4).:

- 5% of cases had reduced internal rotation (IR) range on the left side.

- Nearly 80% had reduced IR on the right side.

- 85.9% had reduced IR on either one or both sides!

- Adductor squeeze test (Falvey, et al., 2015, p. 4).:

- SQ90 = painful in 82.2%

- SQ45 = painful in ~76%

- SQ0 = painful in ~81%

- Cross over test only painful in 41.6% of cases (Falvey, et al., 2015, p. 4).

What can we take away from this? That most have IR ROM deficits, that SQ90 is painful in over 80% of cases and that palpation of the pubic aponeurosis, above the pubic tubercle, is a very common site of pain. Part 2 will discuss how these findings correlated with MRI and what a biomechanical analysis shows about AGP.

Sian

References

All the articles from this blog are open source through BMJ so please read them for yourselves!