Graded Motor Imagery

"Graded Motor Imagery (GMI) is now a part of that revolution, not only as a series of over treatment strategies, but also an increasing reminder that the representation of body in the brain should be considered in all patients” (Moseley, Butler, Beames & Giles., 2012, p. 3).

The Graded Motor Imagery Handbook. Picture courtesy of Google Images.

After completing a course in visual perception and the brain I realised that I might not be understanding the purpose and mechanisms behind graded motor imagery (GMI). This blog is an overview of the key points from the GMI handbook.

It is helpful to establish from the start that GMI is not a preset program but rather a guideline for progressing movement therapies by using motor imagery. It is a treatment that has to be individually tailored and cannot exist as a stand alone without education and interdisciplinary care. The handbook provides a detailed description of the science and theory behind GMI and it’s use, and the purpose of this handbook is to help both clinicians and patients to "build a platform of powerful knowledge on which to base the treatment” (Moseley, Butler, Beames & Giles., 2012, p. 3)

For GMI to be successful it relies on the therapist using clinical reasoning to make decisions about where to begin with treatment. I really appreciate how both Butler and Moseley (in their respective chapters) emphasise the importance of clinical reasoning, building a strong knowledge base, investing in deep learning, challenging pre-established beliefs if they are unhelpful and placing onus on the patient to be an active participant in their journey to recovery. More frequently it comes to my attention that people are searching for the next cure, quick fix or place large emphasis on the diversity of treatment options who can offer. I’ve had many people ask me "What type of therapist are you? Do you do this or that treatment? I’ve heard this treatment is good, is that something you are trained in?" Quite frankly, these people put me off from that initial interaction and I really have to dig deep to invest in helping them and showing them clinical reasoning is far more important than a list of treatment modalities. There is no quick fix for chronic pain. It takes time and perseverance but recovery is possible because the body heals and the brain continues to change and nothing is permanent.

Graded Motor imagery gives the patient control

“We want patient’s to become experts in their problem, not just the passive recipient of the treatment” (Moseley et al., 2012, p.5)

There are 168 hours in the week and we might interact with a patient for somewhere between 30-60 minutes depending how lucky we are. There is a lot of informations that patients will need to take from us in that time, but just remember that you will sit alongside them in their journey, and only they will drive themselves to the destination that they desire.

“When you have a chronic pain state, you will only be with a health professional for about 0.1% of the time. You obviously have to be a self manager, a clinical thinker and a problem solver because the problem belongs to you and those close to you for the rest of time.” (Moseley et al., 2012, p.4)

GMI is about giving patients control and educating them about pain science. This knowledge is a powerful tool in helping them help themselves. As the authors say in the handbook, “we are excited by this knowledge and we want those in trouble to get excited by it as well” (Moseley et al., 2012, p. 6). The placement of these words is extremely powerful and unless you pay attention to it you might overlook how optimistic and enthusiastic these authors are about our ability to gain knowledge and improve. In fact, their passionate vocabulary is sprinkled throughout their work and when I read these words I do feel excited and I feel eager to take on what ever challenge lies ahead.

GMI breaks down barriers to change through sharing of knowledge. No longer is the therapist the person that knows everything and the patient a recipient of treatment. Now they play the biggest role in their own recovery. A huge barrier to acceptance of change is when we present information in a derogatory way. For example the new knowledge that pain is an output from the brain that serves to protect us from potential danger can often be mis-taught as it is all in your head. So it is a continual challenge for clinicians to accept new knowledge, to ensure we know enough about it to use it correctly and to explain pain well, otherwise we run the risk of passing thought viruses onto those who we are trying to help.

As Lorimer shares in chapter 2 of the GMI handbook “the results were, out of memory, sometimes excellent, sometimes horrible” (p.23). This was my experience as well. I was introduced to mirror therapy as a miraculous cure for chronic pain conditions. I experienced many positive outcomes with patients who were poorly responding to other treatments, until I have one patient who had a response so shocking that I stopped using it. Then I realised that while I knew the therapy was useful, I didn’t understand how it works.

Thinking back to when I was taught about GMI it was pitched to me in this way…. For patient’s with complex chronic pain conditions who are deconditioned and have a poor tolerance to daily movements and tasks, there are chronic pain treatments such as mirror therapy that should be explored.

There are 2 mistakes that can occur from thinking about GMI from this perspective.

- The first is that you can wrongly assume reconditioning is a physiological problem at the level of the tissue and not consider the role of central sensitisation.

- The second is that you many assume that changing from an active moment to mirror therapy is a sufficient regression to have effective pain reduction, when rather the GMI should begin with left/right discrimination and progress towards mirror therapy.

This is my clinical story….

Mrs. P had chronic and severe left CRPS and her symptoms seemed to be more unusual than the complexities of CRPS (which is a complex presentation in itself). I never felt like I was completely comfortable with my knowledge of all the contributing mechanisms and driving forces to her continual and very disabling pain. When I first met Mrs. P we got a long really well. I felt there was a strong rapport between us and a level of comfort that enabled lengthy discussions about persistent pain.

After systematically trying many approaches to treatment including cervical mechanical traction, neuropathic pain medications, exercises to address faulty thoracic movements and scapula mechanics, I just didn’t find a long-last pain relieving treatment that enabled this patient to progress their work duties and ability to write for long periods on a white board or work at a computer. I decided to go down the "chronic pain education & management route" and assumed that mirror box therapy would be a reasonably safe place to start.

I explained that with mirror therapy the mind is tricked into seeing movements of the affected side, while in fact it is a reflection and convincing illusion of the unaffected side. Mrs. P was open to trying new treatment and happy to try this approach. As a trial I positioned Mrs. P alongside a full length mirror so that she couldn’t see her left arm. She then began moving her right arm in the mirror and within 10 seconds her pain levels escalated. She stopped and looked at me and asked “what just happened? My left arm is hurting so badly, I have pins and needles all the way from my shoulder to my hand, and I didn’t even move my arm?” I attempted to explain how mirror therapy can activate pain neurotags, that this was not a desired result, that it indicated we should further regress our approach and that I didn’t want her practicing this at home.

When Mrs. P returned later that week she explained that her pain levels were extremely aggravated and that she hadn’t suffered this much since we began treatment. I asked why. She replied that she had been doing mirror therapy everyday for up to 10 minutes at a time. She was completely baffled by how it made her pain worse and interpreted this as a sign that something was seriously wrong with her arm and that we hadn’t found the source of the problem. Safe to say that is it was one of the most self-destructive behaviours I’ve seen before and I suddenly realised that we really weren’t on the same page.

So what could I have improved?

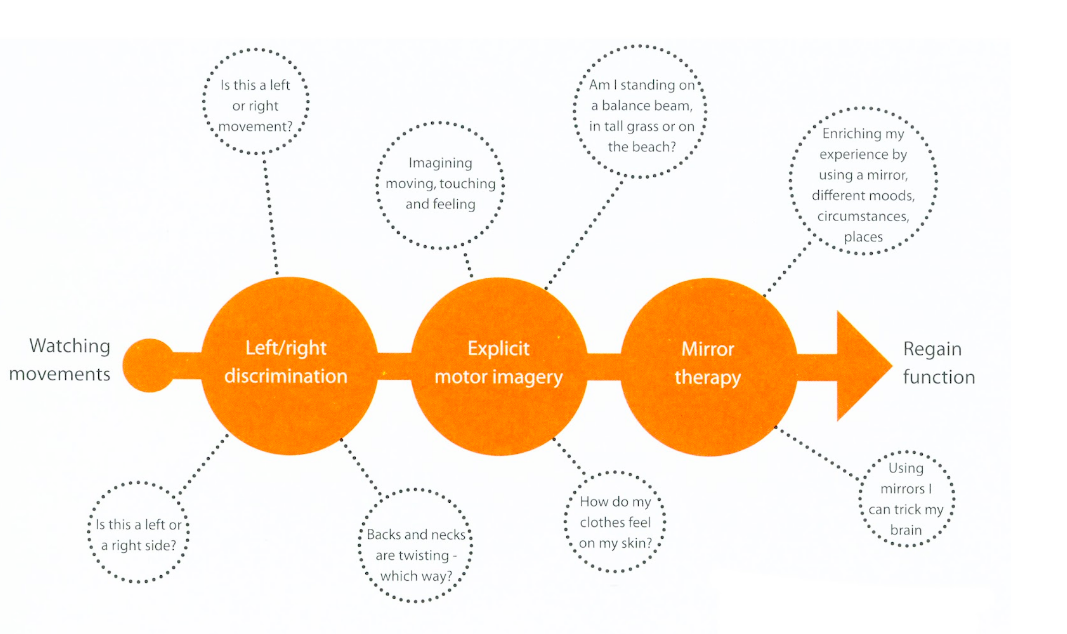

Well I know now, which I didn’t then, that graded motor imagery is a graded approach that doesn’t begin with mirror box therapy. In fact, I started at the very end of the approach. GMI has three main stages of treatment which begins with left/right discrimination, progresses to explicit motor imagery and finishes with mirror therapy.

So the purpose of the remainder of this blog is to share some tips about GMI that I previously didn’t appreciate enough about this approach and that may further assist you in your application of this treatment.

What is the purpose of graded motor imagery?

The GMI process. Image courtesy of Google images

“GMI is essentially a brain-based treatment, targeting the activation of different brain regions in a graded manner. Treatment consists of three different components that include the rehabilitation of left/right discrimination of the affected area, motor imagery rehearsal and mirror therapy. It incorporates the use of computers, magazines, flash cards, mirrors and imagination. It is also hard work.” (Moseley et al., 2012, p.59).

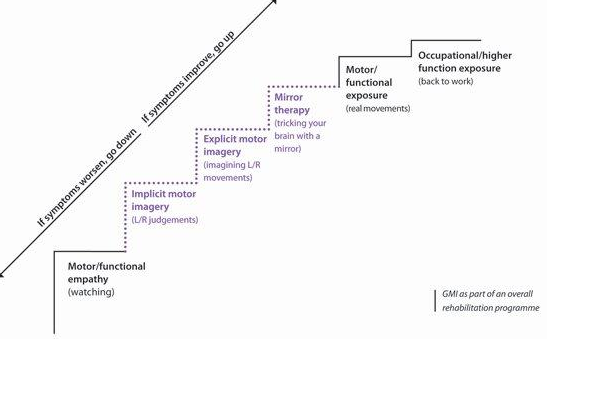

The word ‘graded’ is very important for this treatment approach. The aim is to get under the flare up line. We need to do this with every patient no matter what is wrong with them. Find the flare up line, get under it and gradually re-expose them to load whether it is context, time of day, external distractions or physical load. Gradually build it up without provoking pain, that means without triggering the pain neurotag.

To provide a graded exposure to movement using the visual cortex without activating the premotor cortex and the entire pain neurotags. Something I didn’t completely grasp about neurotags at the time I was treating Mrs. P is that the intention to move can be a strong enough trigger for neurotags. What is really great about GMI is that we are promoting activation of healthy neurotags that help represent the injured body part in a good way, without triggering the primary somatosensory cortex directly. There is a lot of research present and emerging that shows changes in the primary somatosensory cortex, aka the homunculus, in chronic pain conditions which changes the brains visual representation of the body. This cortical disorganisation plays a large role in the development of central sensitisation.

How is GMI structured?

GMI is a gradual process that takes time. Image courtesy of Google Images

Left/right discrimination

In this phase patients practice their speed and accuracy of judging left and right discrimination. This is a form of implicit motor imagery and is known not to activate the premotor cortex. The normal response is to have >80% accuracy and <2seconds response time. Practice 4-5 times a day! Once patients have practiced (a lot) and improved their scores to within the normal range, they can move to the next phase.

“I believe that disengaging the primary motor cortex has two excellent effects. First, it promotes inhibition… which has an effect analogous to restoring laterality or desmudging. The second excelling effect is that it uncouples the hypothesised link between the primary motor cortex and the pain neurotag.” (Moseley, et al., 2012, p. 39).

Explicit motor imagery

“Motor imagery is an imagined movement or in the language of neuroscience - the self-generated representation (neurotic) in your brain of a movement or posture without actually performing the movement or posture. It is a process in which you are aware of yourself thinking about what you are doing, therefore we call it ‘explicit’.”(Moseley et al., 2012, p.79)

In this second stage the patient will imagine themselves performing a movement. Making the imagined movement first person i.e. about oneself is more challenging than phase 1, but doesn’t involved seeing actual movement like phase 3. The authors explain that beginning motor imagery of a body part that is away from the affected body part can be a good way to begin this phase and enable the patient to achieve mastery of the task and knowledge of performance.

Changing the context of the task, where the task is performed, what time of day practice occurs or even just background noise are all ways to increase the demands of this exercise in a gradual way. The aim of explicit motor imagery is to practice movement, even if it is only imagined or observed, without activation of the pain neurotags.

Mirror therapy

Mirror therapy for hand treatment. Image courtesy of Google Images

Mirror therapy is the final stage of graded motor imagery and probably the stage you are most familiar with.

“Interestingly the people who experience the greatest pain relief following mirror therapy are those who have an ability to imaging moving their affected limb. This emphasises the need to have intact motor imagery ability in order to gain the greatest benefit.” (Moseley et al., 2012, p. 86)

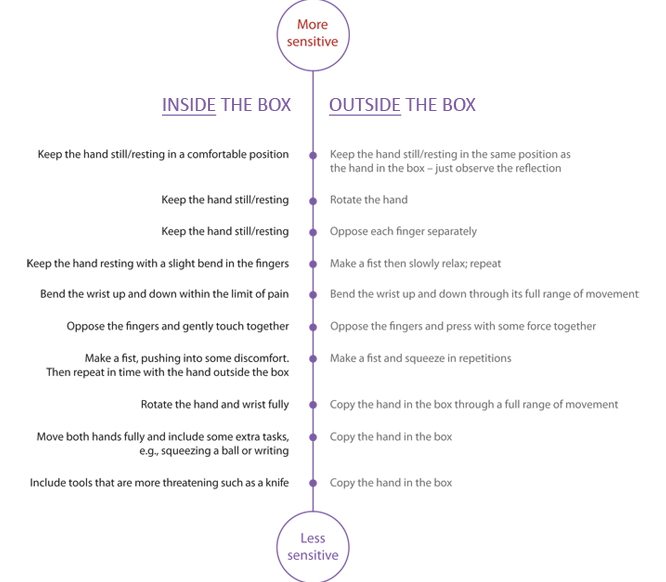

In the handbook there is a list of possible progressions for using the mirror as an illusion of movement. You might begin with the affected hand resting inside the mirror box or out of site in a still position and then observe the reflection of the other hand in the mirror. From observation we can begin to explore rotation, finger movement, hand function, all while keeping the affected side still. Once this is tolerated then movement within pain limits of the affected hand occur simultaneously with full unrestricted movements of the unaffected hand. The exercises is progressed until the hand inside the mirror box is performing the same movements or copying the unaffected hand.

Mirror box therapy progressions. Image courtesy of Google Images

The GMI handbook is an excellent resource for understanding the science behind this treatment paradigm and the specificities of each stage. There are two important messages enforced throughout the book: the first is find a baseline and avoid flare ups, and the second is that this approach takes time and practice. What I find fascinating about GMI is the ability of the illusion to activate motor pathways in the brain without activating pain neurotags. If many things we see are based on visual illusions, then GMI is merely harnessing the illusion of normal movement to strengthen healthy movement neurotags and inhibit/prevent the activation of pain neurotags.

What are the GMI products offered by NOI group?

Vanilla flash cards. Image courtesy of Google images.

- Recognise program for computers - this is a comprehensive tool available for motor imagery exercises available for both the clinician and the patient. You can connect clinicians to patients and track change with time. So if you are interested in storing data and monitoring change then the online account is the best product to choose. If you are just looking for practice then the phone app or flashcards are cheaper and easier options.

- Recognise app

- Flash cards

- DYI

All of the products can be found and reviewed here and there is also a graded motor imagery website.

How does this relate back to my visual perception course?

I realise now that GMI has a strong connection to the visual cortex and that my understanding of how the brain works is improving yet still lacking. GMI is a trick, but thats ok, so many things we see in the real world are illusions, just like the mirror. It doesn’t discredited this approach in anyway. It fact, I am surprised that I only just realised this connection and that they authors have clearly been aware of this for quite sometime now.

Now that I am more aware of the complexities of the visual cortex, the structure of GMI, it’s place in chronic pain treatments, I feel I might spend more time reflecting on my education, explanation of treatments, and clinical reasoning about where to start with different patients.

Each time I sit down to read the work published by MOI group I land up having a good chuckle. I’m so grateful for their engaging writing style and injection of humour and positivity into a topic and treatment area that can be strikingly negative. The following phrase is a mantra of sorts for the NOI group that I feel resonates strongly with my clinical approach:

Have patience, persistence, courage and commitment.

Sian

References:

Moseley, G. L., Butler, D. S., Beames, T. B., Giles, T. J. (2012). The graded motor imagery handbook. Noigroup publications.

Visual perception and the brain. Online course hosted by Causer and taught by Dale Purves from Duke University