Cervical Radiculopathy Part 1 - Clinical Presentation

Image courtesy of Google Images

Neck and shoulder pain are common complaints in the primary care setting and one of the initial goals of clinical assessment is to determine if the shoulder pain is coming from local structures in the shoulder or being referred from the cervical spine. One of the possible causes for referred pain into the shoulder and arm is cervical radiculopathy and the focus for the next three blogs is to look closer at the clinical presentation, assessment, diagnosis and treatment for this condition.

Cervical radiculopathy is the term that describes compression of a cervical nerve root which results in pain and/or sensorimotor deficit in the upper extremity. It can be caused by disc herniation, spondylosis, instability, trauma and rarely, tumours (Caridi, Pumberger & Hughes., 2011). In over 70% of cases of cervical radiculopathy spondylosis of the cervical spine is present and in only 20 to 25% of cases is disk herniation responsible (Corey & Comeau, 2014; Caridi, et al., 2011; Cardette, Phil & Fehlings., 2005).

Cardette, Phil & Fehlings., 2005, p393

Predisposing factors for cervical radiculopathy include: female gender, white race, cigarette smoking, axial load bearing, and prior lumbar radiculopathy (Corey & Comeau., 2014, p. 791).

When a nerve is compressed changes occur in and around the nerve which include: an inflammatory response, changes in vascular flow, and intra-neural edema. A combination of these three events are thought to result in the development of radicular pain (Corey & Comeau., 2014). There is evidence that indicates the release of inflammatory mediators caused by intervertebral disks herniations, which is why anti-inflammatory treatment is commonly recommended in the treatment of this condition (Cardette, Phil & Fehlings., 2005). Another point to note is that you need to consider both the health of the nerve as well as the movement of the nerve in the surrounding interface in order to fully address this condition.

Deciphering referred pain

The diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy is primarily clinical and the first step in diagnosing this condition is understanding the difference between somatic referred and neurogenic/radicular referred pain. In 2012, Smart et al conducted a Delphi-study interviewing expert musculoskeletal physiotherapists to develop a list of signs and symptoms they felt where indicative of nociceptive, neurogenic and central sensitization pain. This is a brief overview of the findings of this series of papers (a previous blog covers them in greater detail).

NOCICEPTIVE PAIN

Nociceptive pain is currently understood to be a process where the peripheral primary afferent neurons are activated by a noxious stimulus which is either chemical, mechanical, or thermal in nature.

- The strongest predictor of nociceptive pain was pain localised to the area of injury with or without somatic referral.

- Clear, proportionate and mechanical pain.

- Clear aggravating and easing factors.

- Pain is usually intermittent and sharp with mechanical provocation.

- Pain may be dull or a constant throb at rest.

- Local signs of inflammation (redness, heat and swelling) are present.

- Nociceptive pain was associated with the absence of – dysaesthesia, night pain, sleep disturbances, burning pain, shooting pain, electric-like pain and the absence of antalgic postures.

- The above signs and symptoms have a sensitivity of 90.9% and specificity of 91% (Smart, et al., 2012).

NEUROGENIC PAIN

- The strongest predictor of peripheral neuropathic pain is pain referred in a dermatomal or cutaneous distribution.

- History of nerve injury or pathology.

- Pain and symptom reproduction with mechanical movement tests and tests producing neural tissue movement/loading i.e neurodynamic assessment.

- Pain is burning, shooting, sharp, aching or electric-shock like.

- Pain is associated with neurological symptoms such as pins & needles, numbness and weakness.

- Patient’s are less responsive to simple analgesia and NSAIDS.

- Patients are more responsive to Lyrica (anti-epileptic) and anti-depression medication.

- High levels of sensitivity and irritability. (Smart, et al., 2012A, p347)

As mentioned above, cervical radiculopathy is a condition that results from compression of a cervical nerve root as it exists the neural foramen. The pain felt by people is radicular in nature and follows a dermatomal pattern corresponding to the level of nerve root involved. It is important to note that compression alone does not necessarily lead to radicular pain unless the dorsal root ganglion is affected (Corey & Comeau, 2014, p.791; Cardette & Fehlings, 2005, p.392).

In cervical radiculopathy pain is caused by compression and involvement of the dorsal root ganglion (outside the spinal cord) (Google images)

Clinical presentation

“Patient history alone can diagnose cervical radiculopathy in over 75% of cases” (Caridi, et al., 2001, p. 266).

Clinical presentation (Corey & Comeau, 2014; Caridi, et al., 2011):

- Symptoms typically are unilateral.

- Referred pain depends on the nerve root level involved.

- While pain is commonly associated with this condition it may be absent in the case a sensory and motor deficit may be the main issues i.e painless neuropathy.

There is no universally accepted criteria for diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy however, since 2005 several articles have been published listing strongly predictable clinical signs and symptoms to form clinical prediction rules (Cardette, Phil & Fehlings., 2005; Wainner, et al., 2003). Many of these research papers discuss the clinical assessment for cervical radiculopathy commenting how a cluster of symptoms helps to strengthen our clinical reasoning and diagnosis. Before we look at the physical exam and clinical prediction rule, it is important to have expectations of what you want to achieve by the end of your subjective assessment.

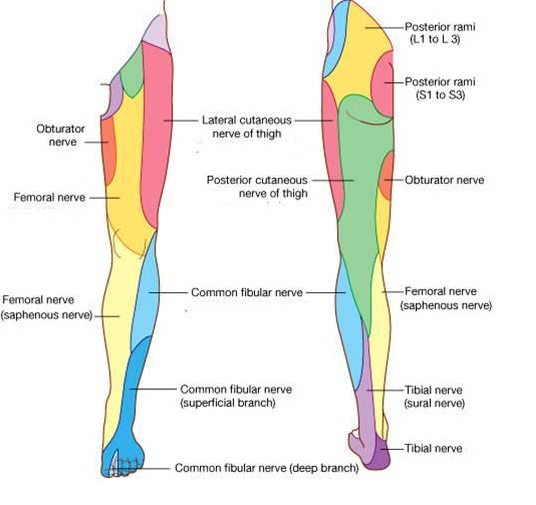

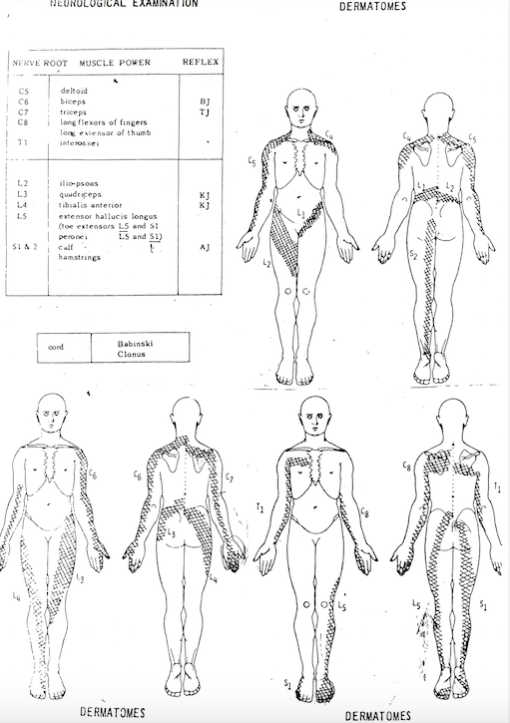

The diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy largely remains a clinical diagnosis without the need for immediate medical imaging (Wainner, et al., 2003). This means that you need to perform a thorough subjective examination to identify this condition as a potential source of the pain. The patient history provides you with the most valuable information at it is during this time that you begin to understand if the pain your patient is experiencing is neurogenic/radicular. I'm sure you've seen these charts many times before but I come back to them again and again. Checking that the pain distribution maps what we know about dermatomal patterns for nerve root pain.

As you can see from the two imaged below, cutaneous and dermatomal distributions are different, meaning that then a nerve root is compressed it follows a different line to that of a peripheral nerve.

Cutaneous nerves of the lower limb (Courtesy of Google Images)

Dermatomes for the lower limb (courtesy of Google Images)

This is the chart I keep on my desk and use to clarify my mapping of pain with my patients. I won't tell them what it is but if they are struggling to map their pain I may quickly show them and ask "does your pain follow this path?" If they are not getting the typical 'line of pain' and more broad and vague patches then it is less likely to be neurogenic in nature.

Understanding dermatomal patterns for the neurological examination

SUBJECTIVE EXAMINATION

At the end of your subjective examination you should have a detailed account of:

- Where the pain is, what it feels like and how it behaves.

- You have questioned for P&N, numbness, weakness, red flags and cord compression.

- You have mapped on a body chart where the pain (and symptoms) are.

- You have noted aggravating and easing factors.

- Severity and irritability

- 24 hours pattern

- Response to medication and previous treatment.

- Current history, past history, general history and social history.

CONSIDERATIONS for ASSESSMENT

1. Gain a detailed description of the symptoms.

Deciphering the exact distribution and quality of referred pain is very important to:

- Differentiate between somatic and neurogenic referred pain.

- Differentiation between involve nerve roots

- Differentiate radiculopathy from thoracic outlet syndrome, ulnar nerve neuropathy and other entrapment neuropathies such as carpal tunnel syndrome.

Upper motor neurones exist within the spinal cord (Google Images)

2. Question for signs of spinal cord compression.

Myelopathy, caused by spinal cord compression, is also a very important condition to question for and assess. Dropping objects, loss of dexterity, Hoffman sign, Babinski sign, hyperreflexia, and clonus are all signs of upper motor neurone lesions (Corey & Comeau., 2014, p. 792). Other compression signs are sphincter disturbances (urinary urgency rather than incontinence), and balance disturbances (Cardette, et al., 2005).

3. Ensure you question for any red flags.

Red flags such as fevers, chills, unexplained weight loss, night pain, previous history of cancer, immunosuppression, IV drug abuse are all factors not associated with radiculopathy (Corey & Comeau, 2014, p. 792; Cardette et al, 2005, p. 393). Other red flags include: aged below 20 or over 50 years, neck rigidity without trauma, dysphagia, and altered consciousness

Conclusion

The focus for the first blog was to revisit typical signs and symptoms of neurogenic pain and dermatomal mapping of nerve roots. Spend time doing your subjective assessment well as it guides so much of the physical exam. If you're not familiar with how a patient presents with cervical radiculopathy then I would recommend reading the case study by Michael Costello (2008). It is very well written and covers the clinical presentation, assessment, diagnosis and progression of treatment over the course of three treatments. [Costello, M. (2008). Treatment of a patient with cervical radiculopathy using thoracic spine thrust manipulation, soft tissue mobilization, and exercise.Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 16(3), 129-135.]

The focus of part 2 & 3 is physical examination and treatment options for cervical radiculopathy.

Sian

References

Anonymous. Pain in the neck and arm: a multicentre trial of the effects of physiotherapy, arranged by the British Association of Physical Medicine. Br Med J. Jan 29 1966;1(5482):253–258.

Apelby-Albrecht, M., Andersson, L., Kleiva, I. W., Kvåle, K., Skillgate, E., & Josephson, A. (2013). Concordance of upper limb neurodynamic tests with medical examination and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cervical radiculopathy: a diagnostic cohort study. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics, 36(9), 626-632.

Carette, S., & Fehlings, M. G. (2005). Cervical radiculopathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(4), 392-399.

Caridi, J. M., Pumberger, M., & Hughes, A. P. (2011). Cervical radiculopathy: a review. HSS journal, 7(3), 265-272.

Cheng, C. H., Tsai, L. C., Chung, H. C., Hsu, W. L., Wang, S. F., Wang, J. L., ... & Chien, A. (2015). Exercise training for non-operative and post-operative patient with cervical radiculopathy: a literature review. Journal of physical therapy science, 27(9), 3011.

Cleland, J. A., Fritz, J. M., Whitman, J. M., & Palmer, J. A. (2006). The reliability and construct validity of the Neck Disability Index and patient specific functional scale in patients with cervical radiculopathy. Spine, 31(5), 598-602.

Cleland, J. A., Whitman, J. M., Fritz, J. M., & Palmer, J. A. (2005). Manual physical therapy, cervical traction, and strengthening exercises in patients with cervical radiculopathy: a case series. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 35(12), 802-811.

Corey, D. L., & Comeau, D. (2014). Cervical radiculopathy. Medical Clinics of North America, 98(4), 791-799.

Costello, M. (2008). Treatment of a patient with cervical radiculopathy using thoracic spine thrust manipulation, soft tissue mobilization, and exercise.Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 16(3), 129-135.

Engquist, M., Löfgren, H., Öberg, B., Holtz, A., Peolsson, A., Söderlund, A., ... & Lind, B. (2013). Surgery versus nonsurgical treatment of cervical radiculopathy: a prospective, randomized study comparing surgery plus physiotherapy with physiotherapy alone with a 2-year follow-up. Spine,38(20), 1715-1722.

Grotle, M., & Hagen, K. B. (2014). Surgery for cervical radiculopathy followed by physiotherapy may resolve symptoms faster than physiotherapy alone, but with few differences at two years. Journal of physiotherapy, 60(2), 109.

Kuijper, B., Tans, J. T. J., Schimsheimer, R. J., Van Der Kallen, B. F. W., Beelen, A., Nollet, F., & De Visser, M. (2009). Degenerative cervical radiculopathy: diagnosis and conservative treatment. A review. European Journal of Neurology, 16(1), 15-20.

Leininger, B., Bronfort, G., Evans, R., & Reiter, T. (2011). Spinal manipulation or mobilization for radiculopathy: a systematic review. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America, 22(1), 105-125.

Raney, N. H., Petersen, E. J., Smith, T. A., Cowan, J. E., Rendeiro, D. G., Deyle, G. D., & Childs, J. D. (2009). Development of a clinical prediction rule to identify patients with neck pain likely to benefit from cervical traction and exercise. European Spine Journal, 18(3), 382-391.

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., & Doody, C. (2012). Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 1 of 3: symptoms and signs of central sensitisation in patients with low back (±leg) pain. Manual therapy, 17(4), 336-344.

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., Thacker, M., & Doody, C. (2012a). Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: part 2 of 3: symptoms and signs of peripheral neuropathic pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain. Manual therapy, 17(4), 345-351.

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., Thacker, M., & Doody, C. (2012b). Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 3 of 3: Symptoms and signs of nociceptive pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain. Manual therapy, 17(4), 352-‐357.

Swezey RL, Swezey AM, Warner K. Efficacy of home cervical traction therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. Jan-Feb 1999;78(1):30–32.

Valtonen EJ, Kiuru E. Cervical traction as a therapeutic tool. A clinical anlaysis based on 212 patients. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1970;2(1):29–36

van der Heijden GJ, Beurskens AJ, Koes BW, Assendelft WJ, de Vet HC, Bouter LM. The efficacy of traction for back and neck pain: a systematic, blinded review of randomized clinical trial methods. Phys Ther. Feb 1995;75(2):93–104.

Wainner, R. S., Fritz, J. M., Irrgang, J. J., Boninger, M. L., Delitto, A., & Allison, S. (2003). Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy.Spine, 28(1), 52-62.

Waldrop, M. A. (2006). Diagnosis and treatment of cervical radiculopathy using a clinical prediction rule and a multimodal intervention approach: a case series. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 36(3), 152-159.

Wong AM, Lee MY, Chang WH, Tang FT. Clinical trial of a cervical traction modality with electromyographic biofeedback. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. Jan-Feb 1997;76(1):19–25.