Assessment of acute knee injuries with snow-specific skills

This week Rayner & Smale welcomes Holly Lipson to the blog. Holly is a graduate physiotherapist from Anglesea, Victoria, passionate skier and surfer, and all round adventure lover. What we share in common is our connection through the Olympic Winter Institute of Australia Physiotherapy network.

Both Holly and I had the pleasure of working with the Australian and New Zealand Para Alpine teams this season and Holly is going to share her experience on winter sport physiotherapy and tips she has learnt about managing acute knee injuries in the snow-environment. Holly is a passionate and vibrant Physiotherapist and I’ll leave it to her to tell you the rest…

Physiotherapy - what a career! The choice to enter the physiotherapy industry was something that appealed to me not only because I have a passion for sport, helping people and problem solving, but also because it was a profession that could allow me to blend my passion for skiing with work.

For the past two Southern winters, I have been fortunate enough to work at Altitude Physiotherapy at Falls creek, Victoria. As is Sian, I am also a certified physiotherapy provider for the Olympic winter institute Australia, having recently returned from a month in Europe with the successful Australian and New Zealand para alpine teams. In the midst of all this I am currently halfway through my ski patrol traineeship. There is never a dull moment during the winter months!

The mix of ski patrol and physiotherapy roles has been very rewarding. Each role complimenting the other. I can be present in this unique window of time, i.e. from the moments after the injury occurs on the snow, through to the clinic the next day. This has given me an appreciation for how unique each injury is, even though they occur in common ways. Even if identical structures are injured in two different people; the presentation, rate of recovery and treatment pathway can vary considerably. It has taught me the valuable lesson of looking at the context of the injury in relation to the person in front of me.

The focus of this blog is to share my clinical approach and tips to managing one of the most commonly seen injury of the slopes, acute knee joint injuries (Xian, et al., 2005). One of the biggest challenges for Physiotherapists in managing acute knee injuries in the clinic is time. Often, by the time the patient comes through the door, their knee is swollen, painful and movements are guarded. Making assessment challenging. From my experience, the best time to assess the acutely injured knee is within the first hours, which in the snow-environment is much more feasible than other sporting environments.

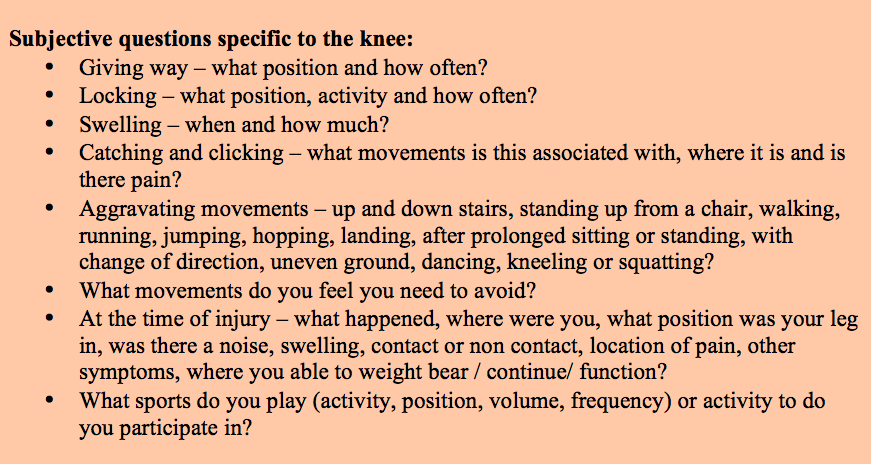

Let’s begin with the subjective assessment and cover some of the key points I look for while interviewing the patient:

- Mechanism of injury – with skiing and snow boarding, this gives you so much information from which you can begin to develop a hypothesis list.

- Severity – could they continue to ski/snowboard? Could they stand up? Did they need ski patrol to take them down the mountain?

- Swelling – when did it occur?

- Other symptoms – clicking, locking, giving way, feeling unstable.

- Pain location – where is the pain and can they point to it?

- If they are able to weight bear – what movements provoke or ease the pain? Is there a way they can walk or stand which is more comfortable?

- If they can’t weight bear – why? Are they limited by pain, weakness, or feeling unstable?

- Ski experience – what level of experience do they have? What level of function are they expecting to get back to? A recreational skier versus a professional athlete will have completely different levels of strength, balance, skill and expectations/requirements for recovery. This will impact the speed and direction of your treatment pathway.

- Past knee injuries – how did they occur? What was the recovery process and timeframe? Did they recover back to 100%?

- If they are an athlete:

- Are they training or during competition?

- Is there a buffer between now and the next competition?

- What is they main discipline?

Other special questions for the knee which can be generalised to other environments may include:

When working on the snow my assessment will vary. The first priority is primary survey (basic life support – DR ABC) and then completing a secondary survey to establish what possible injuries have occurred. Once I have established that a soft tissue injury has occurred and the person is otherwise stable and safe, the initial assessment needs to be precise and quick. On the snow, you don’t have access to a treatment room and the environment is often freezing making it unrealistic to expose the skin at times. Bulky ski gear and boots and make active and passive movement testing difficult (but not impossible) at times. Pain descriptions, and a detailed MOI is important. A useful tip is to questioning friends, family or bystanders that might have witnessed the incident if the person can’t recall what exactly happened. Some important things to note:

- Was there a collision or was the person alone?

- Did the bindings release?

- Was the snow quality wet, dry, icing, or powder?

- How did they fall and land?

- Did they injury any other body parts?

- Take your time and be specific where possible.

Moving into the clinical setting now or maybe just the medical tent… I’d like to go over the physical examination of an acute knee injury. As mentioned above – timing can be a limiting factor. We all know that there is a large battery of clinical tests for the knee, all of which has varying levels of sensitivity and specificity. With an acute, painful and swollen knee, and let’s not forget the apprehensive and concerned patient, it would be unrealistic to think that every test can be performed on the first assessment. Instead, I try to focus on working through my hypothesis list to determine in an intra or extra articular injury has occurred, if muscular, ligamentous or other articular structures are damaged, and if immediate referral is required. I will also perform a quick neurovascular assessment of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries pulses, sensation and quick motor assessment. Being in the cold environment, people will often have reduced perfusion, sensation and motor control, so it is important to assess these functions in a warm environment.

Due to the rotational and flexion forces involved in skiing and snowboarding, and large compressive forces that occur during landings, ACL injuries, collateral ligament injuries and tibial plateau fractures are common.

Below is my process for the initial assessment. This list is not the entire physical examination that you may be familiar with, but more of an overview of the key elements I try to focus on in this environment.

Observation

Are they walking? Are they able to weight bear normally or do they walk with a limp? Do they come in on crutches or with other supportive devices. This is going to give me information about stability, apprehension and load tolerance.

How do they stand? Is there an antalgic posture such as a fixed flexion deformity or tibial internal rotation? Collateral ligament injuries won’t like to be kept in terminal extension and neither will acute ACL injuries. Acute PFJ injuries whether subluxations or compression injuries might prefer a position of extension and be apprehensive of flexion. These are just a few considerations to keep in mind.

Is there any swelling or visible deformity? Where is it and how does it present? Bruising, redness or a big puffy knee. This tells us about intra-articular effusions, extra-articular haematomas and possible suprapatellar bursitis. Snow sport injuries often occur at high speeds and can be very traumatic. Have a good look at the patient before moving and touching them.

Palpation

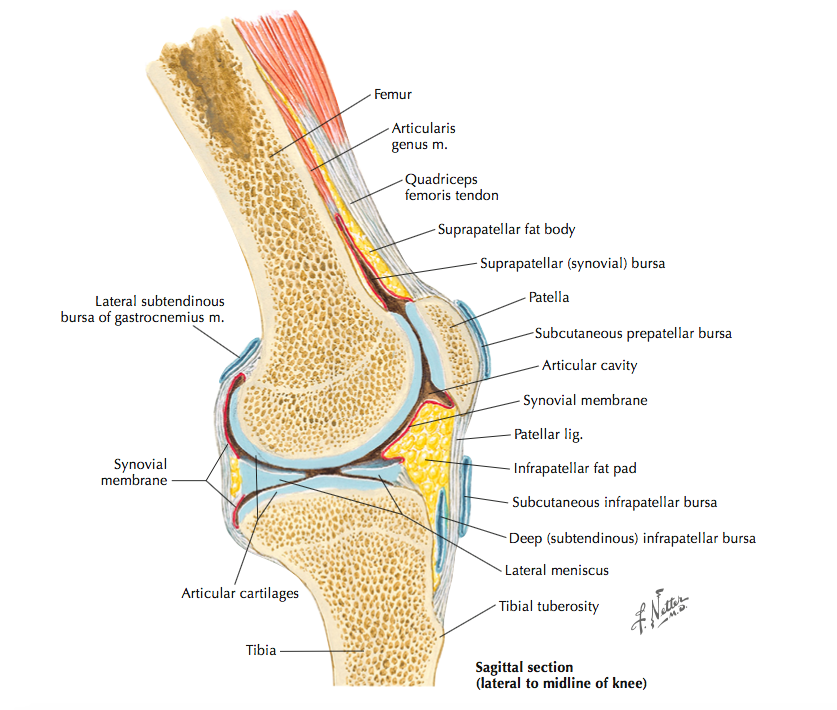

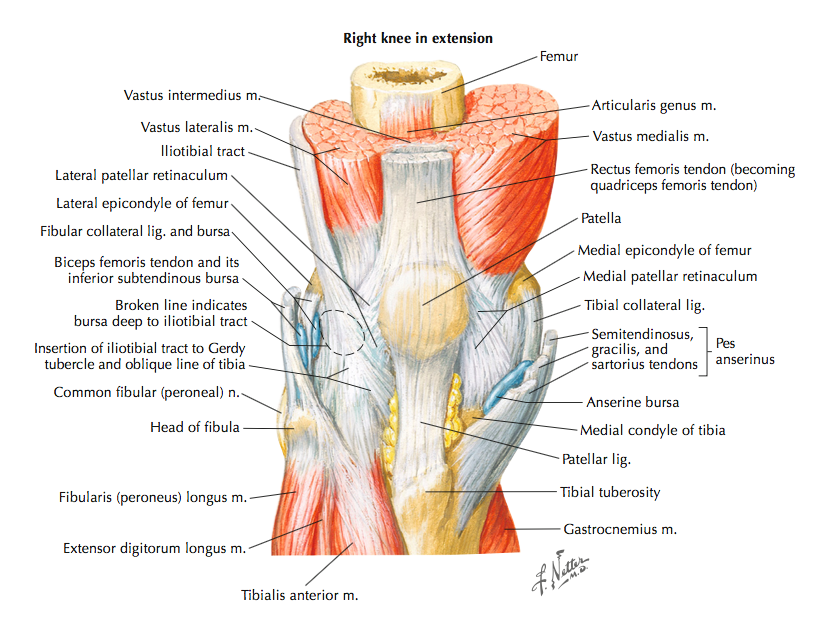

Once the patient is on the plinth have a better inspection of the knee and areas of swelling and then begin my palpation. As a refresher let’s take a look at the anatomy of the knee and review the key structures to consider during palpation. (Images courtesy of Google Images).

Active and passive movements

This is quick and simple test where you can gain information about pain and guarding. It is important to make sure you have a supportive grip of the joint especially in the apprehensive patient when taking the joint into passive range. Good and supportive manual handling can be a big factor in gaining the patients trust in you and can set the scene for the rest of the session. Aside from looking at what the patient is able to do actively, you are also using this time to workout how you might need to adjust your handling for the special tests.

Special tests

Sweep test: The sweep test is a great test to try objectively measure the about of intra articular fluid as apposed to making an observational comment on swelling. It also has a high inter-rater reliability, quoted in the literature as being 73% agreement between clinicians (Patterson Sturgill, Synder-Mackler, Jo Manal & Axe, 2009). More info and a video demonstration can be seen here.

Valgus and Varus stress in 0 and 30 degrees. Is the primary test recommended for assessing the integrity of the medial collateral and lateral collateral ligaments. If you are feeling laxity at 0 degrees then this indicates a high-grade tear, as the knee is most congruent in this position. Take care not to push the femur into too much internal rotation when performing this test as sometimes this can be mistaken as “laxity” or in turn will not allow you to feel true laxity.

Lachmans: This test has been shown the best at ruling out an ACL injury and when looking solely at sensitivity and specificity values, the literature shows it to be the best overall test for ruling in or out ACL injury (Ostrowski, 2006). However, I find ACL testing hard in the early stages. After an hour or so, most people with an ACL injury (or any form of significant knee pain for that matter) will guard.

Pivot Shift: The literature reports this test to be the best at ruling in an ACL rupture (Ostrowski, 2009). However, I rarely use this test in the acute stages. It is really challenging to perform this test on a painful and swollen patient. And although good in theory, I find clinically this often isn’t a suitable test

McMurrays: This is a tricky one. As with the pivot shift, if the knee is painful and swollen, no patient is going to like you doing this test and it can irritate and flare them up further. I find you can get enough information from a good subjective assessment and palpation skills to diagnose a meniscus injury without the need for Mcmurrays. The reliability of this test is also quite low and the sensitivity of this test has a wide range (27%-70%) meaning when using the McMurrays in isolation, the chance of missing a tear is high (Hing et al, 2009).

Dial test: As discussed in the excellent entry by Grant Freckleton, Injuries to the posterolateral complex are often missed and are commonly associated with injury to the ACL, PCL, or both (Fanelli & Larson, 2002; LaPrade & Wentorf, 2002). A lot of the knee injuries we see at the snow are high speed and traumatic meaning the liklihood of multi structure injury is high. Injuries to the PLC should not be missed as early intervention is key and these guys don’t do well with conservative management (Cooper, McAndrews & La Prade, 2006).

Tap test: By this I mean a solid tap along the Tibial plateau to help identify if there is a fracture present. If so the patient will jump and a sharp radiating pain is likely emanated.

Conclusion

The main goal for the initial assessment is to determine if the patient can continue to compete/ski, if referral for medical imaging is required, or if conservative treatment can be commenced. I try to follow the mindset of “when in doubt, ask for a second opinion”. Each individual is different and while we may be efficient at performing the battery of tests above, each knee and person will feel and respond slightly differently. So if I have any doubt, I will ask a colleague for a second opinion and from experience, my patients appreciate this and feel that it shows genuine care for their injury.

Hopefully this blog has demonstrated how a physiotherapy assessment will vary in winter sports and shown how we can use our physiotherapy framework as a base for assessment and then branch out into the snow-specific sporting and environmental factors.

Hope to see you all on the slopes this winter!

Holly & Sian

Contact Holly via twitter or her blog The everyday physiotherapist.

References:

Behairy, N. H., Dorgham, M. A., & Khaled, S. A. (2009). Accuracy of routine magnetic resonance imaging in meniscal and ligamentous injuries of the knee: comparison with arthroscopy. International Orthopaedics, 33(4), 961–967.

Fanelli, G. C., & Larson, R. V. (2002). Practical management of posterolateral instability of the knee. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 18(2), 1-8.

Hing, W., White, S., Reid, D., Marshall, R. et al (2009). Validity of the McMurrays Test and modified versions of the test: A systematic literature review. Journal of Manual and manipulative therapy. 17 (1). 22-35

LaPrade RF, Terry GC: Injuries to the posterolateral aspect of the knee: Association of injuries with clinical instability. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:433–438

Ostrowski, J. A. (2006). Accuracy of 3 Diagnostic Tests for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears. Journal of Athletic Training, 41(1), 120–121.

Patterson Sturgil, L., Synder-Mackler, L., Jo Manal, T. & Axe, M. (2009). Interrater reliability of a clinical scale to assess nee joint effusion. Journal and orthopaedic & sport physical therapy. 39 (12).

Sanchis-Alfonso V, Martinez-Sanjuan V, Gastaldi-Orquin E, (1993) The value of MRI in the evaluation of the ACL deficient knee and in the post-operative evaluation after ACL reconstruction. European Journal of Radiology.16:126–130.

Xian, H., et al. (2005). Skiing and snowboard related injuries treated in U.S. Emergency departments, 2002. Journal of trauma, infection and critical care. 58(1), 112-118.