Hip: FAI - a Condition That Matters

Joanne Kemp. Image courtesy of Google Images

During my recent trip to Melbourne I had the pleasure of attending the Victorian APA end of year breakfast. Each year the Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) hosts a breakfast with a keynote speaker and panel discussion. This year Joanne Kemp, PhD, APA-titled Sports Physiotherapist spoke on the topic of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI).

Joanne has been involved in hip research for many years and after reading several of her published papers, it was a privilege to listen to her present in person. Joanne delivered a polished and extremely well researched lecture on FAI, why it matters and what we should be doing as Physiotherapists to best treat our patients.

Over time I’ve witnessed the increasing trends in the recognition and diagnosis of FAI as a cause of hip pain, however, similar developments in rehabilitation protocols have not been as evident. Clinically I feel there is a strong association with the diagnosis of FAI and the progression to arthroscopy surgery. Prior to attending this breakfast I had a pessimistic impression about this condition and never felt positive about treating patients with FAI, often thinking well if you have FAI you'll probably land up having surgery.

Joanne’s lecture gave me a new positive perspective on this condition and broadened my knowledge about the role of physiotherapy and treatment options outside of surgery. I left feeling encouraged about how much more we could potentially be offering patients. There were many ways in which my understanding of FAI shifted during this lecture, some of which I wish to share with you in this blog.

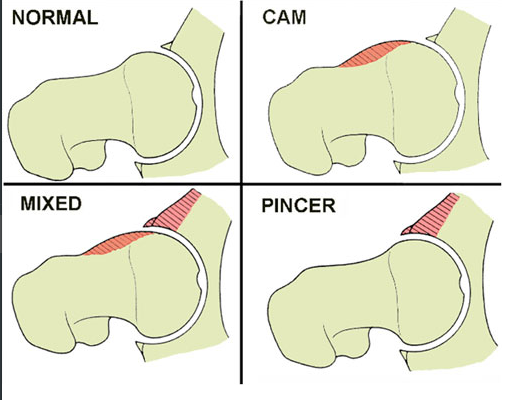

A CAM lesion is not a pathology

There are three possible morphological changes in the bony structure of the hip. A cam lesion refers to additional bone growth on the femoral neck and is measured with the alpha angle on XRAY. A pincer lesion refers to additional bone growth on the acetabular rim. If both cam and pincer lesion are present then the presentation is labelled as mixed.

Image courtesy of Google Images

“While much speculation exists, the prevalence of CAM morphology in the general population is unknown and the presence of a CAM abnormality does not inevitably lead to symptomatic FAI” (Freke, et al., 2016, p.1). Like many other morphological changes we see in asymptomatic people, cam lesions are not a pathology. Therapists need to be cautious in assuming that all changes we see on medical imaging are a problem as often they are not. If people with cam lesions continually take the hip into positions of impingement however, FAI may develop.

“FAI is a clinical condition, where affected patients may present with a morphological variant in hip shape on radiographs, with or without associated labral and/or chondral pathology, resulting in increased hip/groin pain and reduced activity and quality of life” (Freke, et al., 2016, p.1).

Image courtesy of Google Images

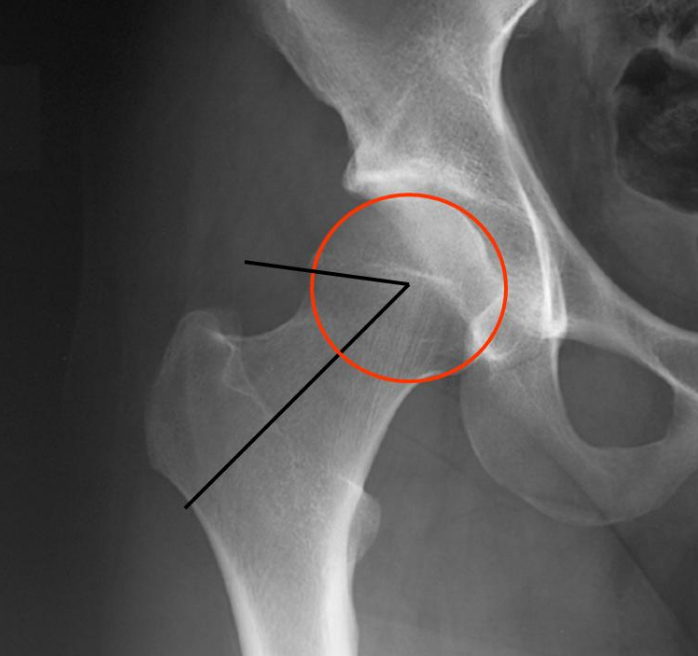

FAI is a clinical diagnosis

FAI is a clinical condition that cannot be diagnosed with only one sign, one symptom or only morphological changes on medical imaging. According to the Warwick agreement we now can make the clinical diagnosis of FAI with each of the three factors being present (Griffin, et al., 2016):

- Positive imaging findings of bony morphology - for CAM or pincer morphology AP pelvis and Dunn 45 view are gold standard for imaging and for associated labral or chondral pathology, MRI is gold standard.

- Symptoms of hip and/or groin pain.

- Signs of FAI, including physical impairments (reduced muscle strength and functional control) and positive impingement tests (FADIR and IR in flexion).

FAI is a disease continuum beginning early in life

I have never considered FAI as a continuous disease process and it was really interesting to hear about how studies are now linking FAI to developmental dysplasia early in life and the progression to OA later in life. “Studies to date have demonstrated that FAI and acetabular dysplasia are strongly associated with the increased severity of labral pathology and may play a significant role in the development of early hip OA” (Kemp, et al., 2012, p. 632). The implications of this knowledge changes how we might address this patient population. Perhaps we need to focus on more thoroughly rehabilitating the young athlete after their first hip pain presentation or perhaps we need to more extensively modify the activity of the older athlete who is continually overloading their hip into impingement positions? This was a key message that I felt Joanne was trying to convey to the audience, that our contact with hip pain patients may not be a single moment in time and we may need to change our perspective of our role and involvement in their ongoing recovery.

Range (ROM) is not the primary focus of rehabilitation

Joanne presented a recent systematic review published in 2016 which investigated the physical impairments associated with symptomatic FAI. The results of this systematic review were different to previous papers challenging the idea that range of motion is limited in patients with FAI. The systematic review showed that there isn’t strong evidence to say that symptomatic FAI has a greater loss of range of movement in flexion/adduction/internal rotation as we may have previously expected. “This suggests that while CAM abnormalities may create increased bony impingement/abutment that can result in soft tissue damage, symptomatic FAI does not appear to be associated with lower hip ROM” (Freke, et al., 2016, p.10). “Thus, while further high quality studies are clearly needed, the best available evidence suggests that ROM is not impairment in individuals with symptomatic FAI and should not be the primary target for treatment regimes” (Freke, et al., 2016, p.10).

The trunk is impaired and impacts the hip

Ross et al (2014) conducted a study to investigate the impact that pelvic tilt had on hip range of movement and acetabular version visualised on 2 and 3 dimensional imaging. What they found is that anterior and posterior pelvic tilt have significant change in both acetabular positioning and hip range of movement.

- "Anterior pelvic tilt resulted in significant retroversion and a decrease in internal rotation in 90° of flexion of 5.9° (P < .0001) and internal rotation in 90° of flexion and 15° adduction of 8.5° (P < .0001), with a shift in the location of osseous impingement more anteriorly.

- Posterior pelvic tilt (10° change) resulted in an increase in internal rotation in 90° of flexion of 5.1° (P < .0001) and internal rotation in 90° of flexion and 15° adduction of 7.4° (P < .0001), with a superolateral shift in the location of osseous impingement” (Ross et al., 2014).

The authors concluded that dynamic pelvic orientation significantly influences the functional orientation of the acetabulum. This study also found that people with impingement have reduced trunk control bilaterally, supporting the need to include trunk rehabilitation in treatment. This has implications for therapists rehabilitating patients with symptomatic FAI as not only should the trunk be a strong focus of rehabilitation but pelvic positioning during exercise and ADLS can have an impact on the positioning of the hip and range of movement.

Shifting our focus to quality of life

Joanne presented many papers throughout her lecture exploring the physical impairments that have been found in patients with symptomatic FAI and hip OA. What studies have found is that quality of life is significantly impaired in individuals with FAI and that following rehabilitation, many of these patients never return to the quality of life of a comparative healthy person.

Physically this population is impaired pre-operatively and post-operatively in the following areas:

- Reduced muscle strength

- Reduced dynamic balance

- Reduced functional task performance

- Increased impingement with single leg squat tasks

- Reduced trunk function

- Alterations in gait

- Possibly poor ROM

Giving these seven areas of possible physical impairments, it is clear that if Physiotherapists want to take the lead in rehabilitating FAI patients conservatively, we need to provide a comprehensive rehabilitation program address each of these facets. Joanne emphasised that we aren’t doing enough for this patient population.

Treatment should focus on the following areas:

- Hip strengthening in each plane of movement, not just the gluteals but also into hip flexion, adduction, internal rotation

- Retraining trunk control and endurance bilaterally

- Retraining single leg balance bilaterally

- Focus on sport-specific functional training

- Optimise ROM but doesn’t push for end or range

- Modify ADL and positioning to minimise joint loading

The continual search for stronger evidence shouldn’t discourage our practice

Joanne, and many other researchers I’ve previously met, have often said the same thing “a lack of evidence for a treatment effect is not the same as evidence for a lack of treatment effect”. We still don’t have strong evidence for treatment. Physiotherapists need to take the lead on rehabilitation of patient with symptomatic FAI and deliver a more comprehensive rehab program and continue to review the patient for longer periods of time. We know now that this is a continuum disorder and most likely the early signs of Hip OA. It is not good enough to treatment patients in the short term without evaluating their progress intermittently over time, adjusting their rehabilitation programs and ensuring they have the most optimal QOL.

If we change our view of this condition from that of an acute exacerbation to one of a disease progression towards osteoarthritis, we need to commit to developing long term relationships with our clients. We need to educate them about impingement positions during ADLs that may be contributing to the cumulative overload on their hips. We need to educate them about the nature of this condition and realistically set their expectations about prognosis and how much arthroscopy can do to change disease progression. And, we need to empower our patients with the best rehabilitation program allowing them to gain the most function from their hip and regain the best quality of life. It is not enough to become more aware that this condition exists. It was clear during her lecture how passionate Joanne is in this area, her extensive knowledge on the condition and related conditions and how much work we have to do as a profession if we are going to successfully impact these patients and help them with their long term recovery.

I want to thank the APA for hosting the breakfast and Joanne for such a thought-provoking lecture on FAI. After this lecture I was left with an increased curiosity to know more about this condition, explore the current post-arthroscopy rehabilitation programs and understand more about how we can rehabilitation our patients with hip and groin pain. Hopefully a few more blogs will emerge in the future and until then, I hope you too feel encouraged to spend more time rehabilitating your patients to a higher level of function and quality of life.

Sian :)

References

Freke, M. D., Kemp, J., Svege, I., Risberg, M. A., Semciw, A., & Crossley, K. M. (2016). Physical impairments in symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of the evidence. British journal of sports medicine, 50(19), 1180-1180.

Griffin, D. R., Dickenson, E. J., O'Donnell, J., Awan, T., Beck, M., Clohisy, J. C., ... & Hölmich, P. (2016). The Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. British journal of sports medicine, 50(19), 1169-1176.

Kemp, J. L., Collins, N. J., Makdissi, M., Schache, A. G., Machotka, Z., & Crossley, K. (2011). Hip arthroscopy for intra-articular pathology: a systematic review of outcomes with and without femoral osteoplasty. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2011.

Ross, J. R., Nepple, J. J., Philippon, M. J., Kelly, B. T., Larson, C. M., & Bedi, A. (2014). Effect of changes in pelvic tilt on range of motion to impingement and radiographic parameters of acetabular morphologic characteristics. The American journal of sports medicine, 0363546514541229.

Weinans, H. (2016). What causes cam deformity and femoroacetabular impingement: still too many questions to provide clear answers. British journal of sports medicine, 50(5), 263-264.