Deciphering the driving mechanisms in chronic low back pain

As Physiotherapists we are required to provide our patient's with an assessment to determine why they have pain and where that pain is coming from. But what if you just couldn't say what it was?? What if the radiological scans are unremarkable and the G.P says that medically they are clear?

What do you call it?

How do you label it?

What structure are you going to treat?

What structure is your patient going to blame?

These are all questions I've toiled over many times, calling it one thing, then changing my mind, only to suspect at the end of it all that maybe there was no single structure at fault?

What about a no-blame policy?

How fantastic would that be??? Well such a classification system already exists. Peter O'Sullivan is an Australian Specialist Musculoskeletal Physiotherapist (as awarded by the Australian College of Physiotherapists in 2005), and Professor of Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy from Curtin University in Perth, Australia. He is recognised internationally as a leading clinician, researcher and educator in the management of complex musculoskeletal pain disorders. Peter is at the forefront of research in chronic low back pain and one of his main goals is to reduce the gap between what science tells us and what clinicians and patients know.

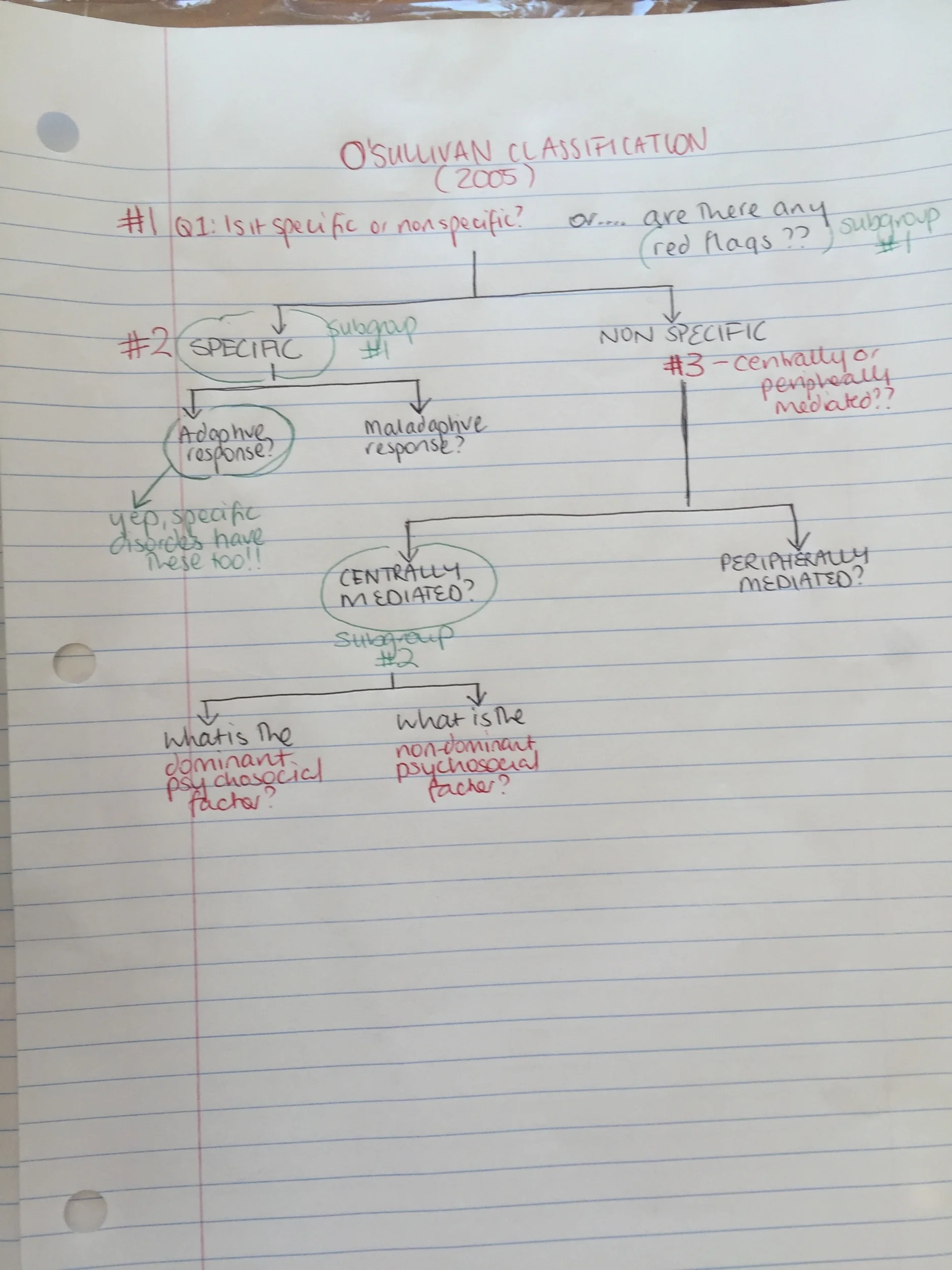

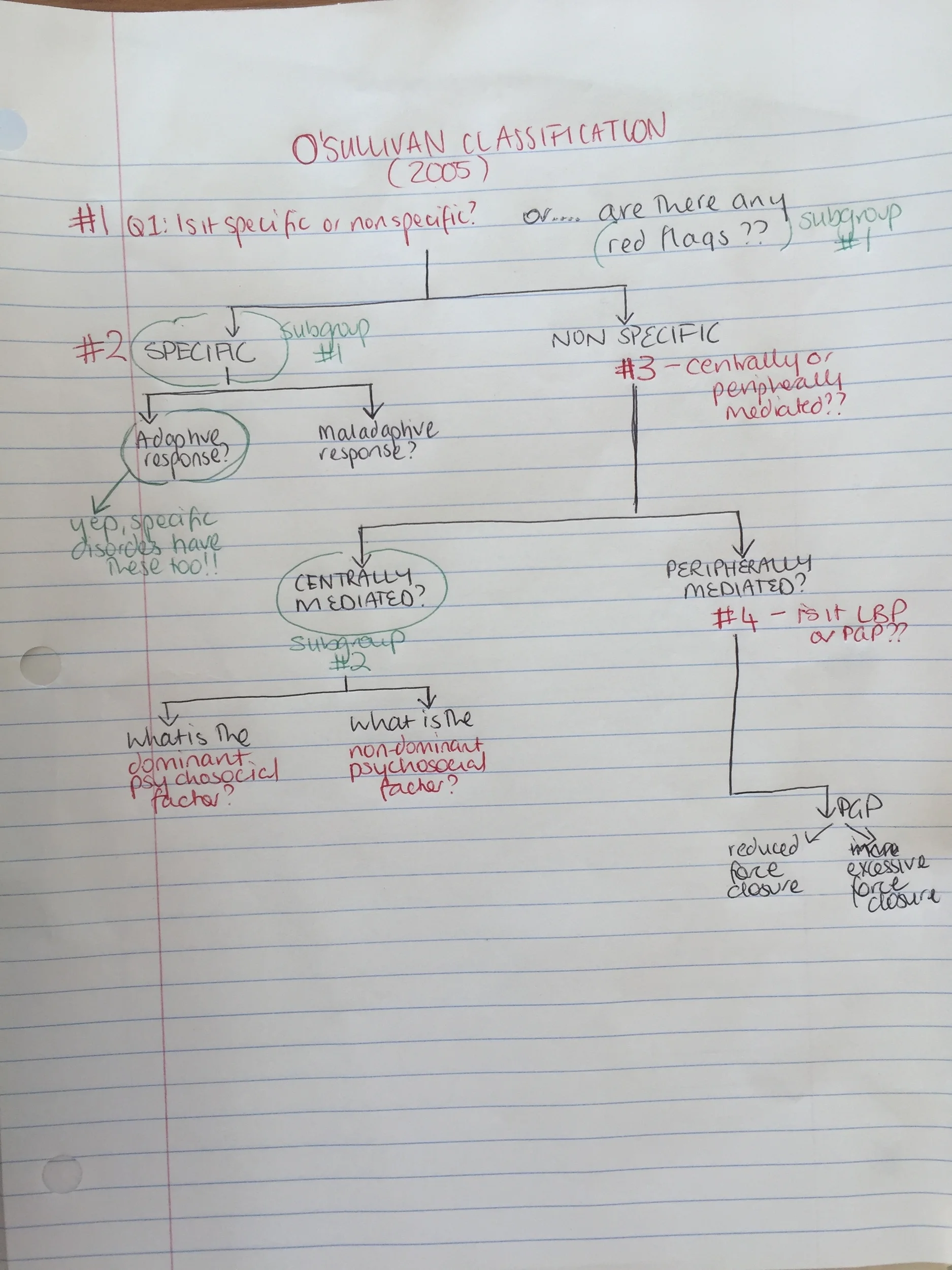

In 2005, O'Sullivan published a masterclass paper which proposes a new model and classification system that allows us to determine what the main driving mechanisms is that is perpetuating, amplifying and contributing to the chronic pain disorder. This blog is all about this framework, breaking it down step by step, to help others see how using this classification system makes a complex pain disorder less complicated.

The conundrem of diagnosing low back pain (LBP)

When it comes to discussing the diagnosis of low back pain (LBP) there are times when it is really hard to put a label on pain because it is hard to say is it one specific thing. Such a blurry diagnosis. In fact 85-90% of people with LBP are in this category making the blurry diagnosis the majority.

Just because we can't label it doesn't mean we can't determine why it is occurring.

"Only 1-2% of people presenting with LBP will have a serious or systemic disorder, such as systemic inflammatory disorders, infections, spinal malignancy or spinal fracture" (O'Sullivan & Lin., 2014, p.9).

5-10% fall into the category of specific low back pain which includes:

- Radiculopathy from disc pathology (protrusion, extrusion, bulge), synovial cyst, and spondolytic changes.

- Lumbar spine stenosis.

- Spondylolisthesis.

- Modic changes.

- Fracture.

- Infection.

- Tumour.

- Inflammatory disease

The remaining 85-90% fall into the category of non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) (Dillingham, 1995; O'Sullivan., 2005; O'Sullivan & Lin., 2014). This is not to say they all go into the same basket though. People with low back pain are not a homogenous group and therefore need to be managed in different ways with each group having different needs. People with LBP can also present with a wide range of bio-psycho-social characteristics and it is up to us to identify the primary driver.

Let's go through step by step how the O'Sullivan classification works. I first read this article in 2010 and at the time it was a little over my head. I just keep coming back to it. Each time I read it, it becomes a little clearer. The more people I see, the more I read it, the clearer the patterns become.

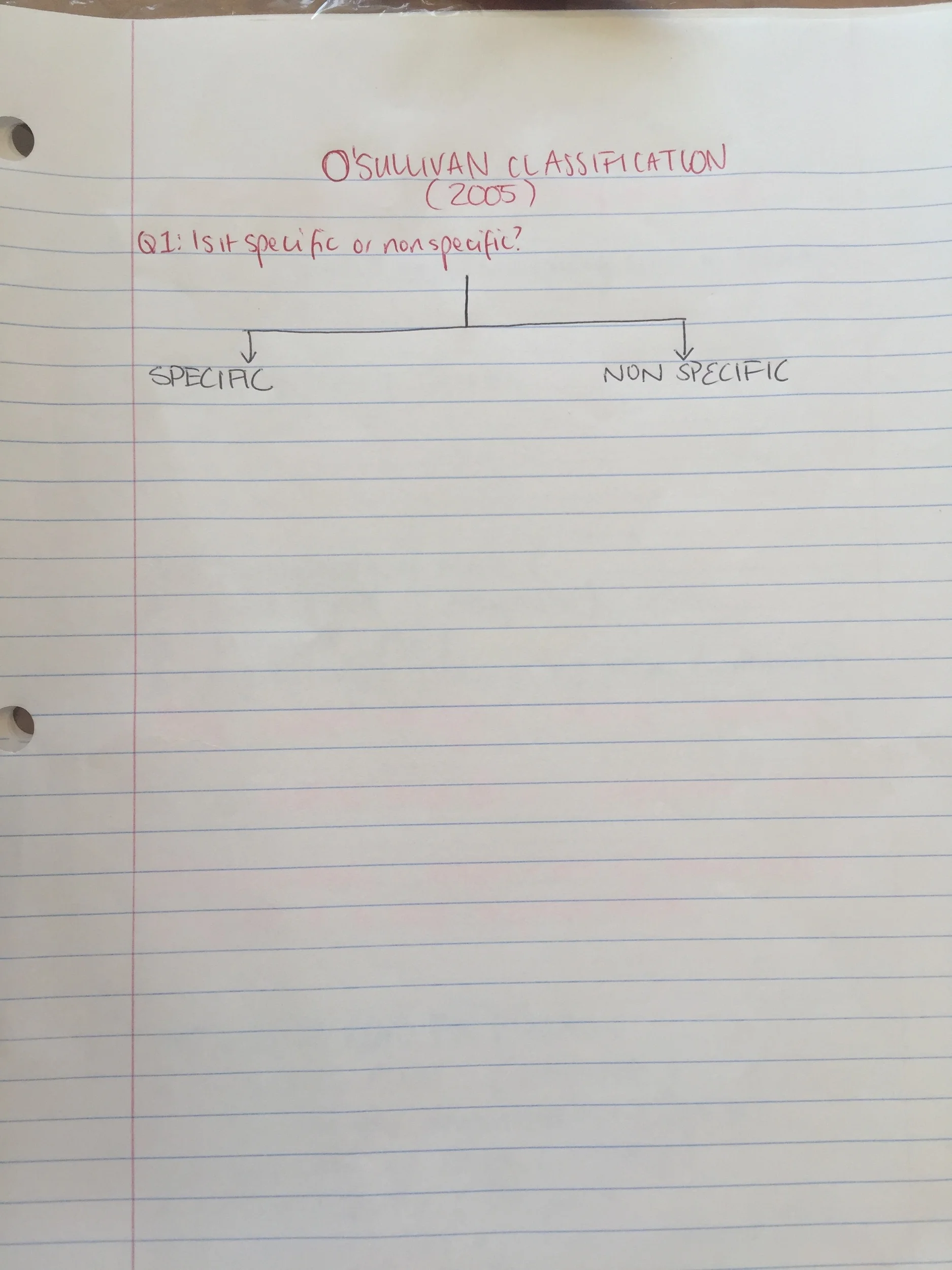

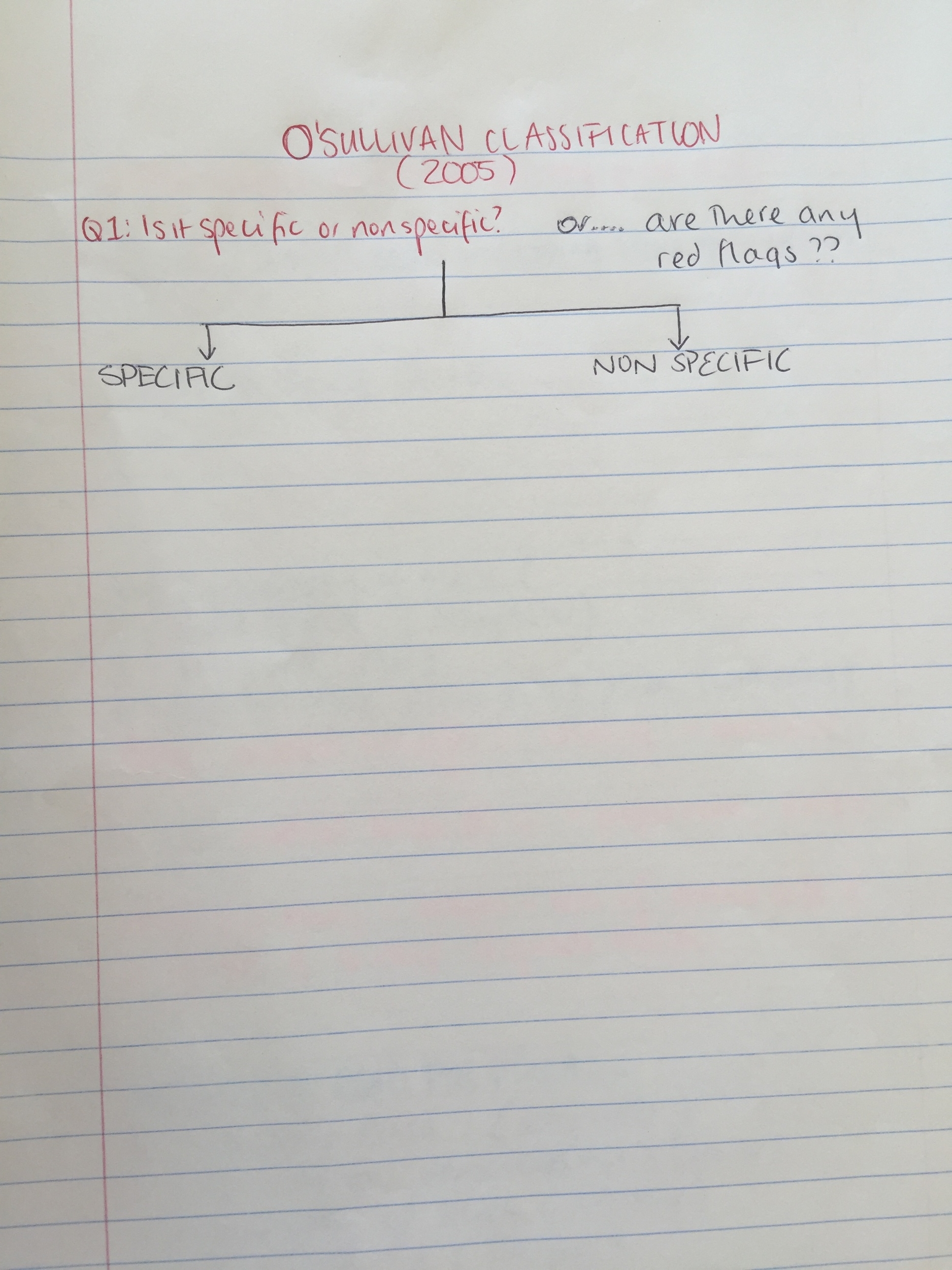

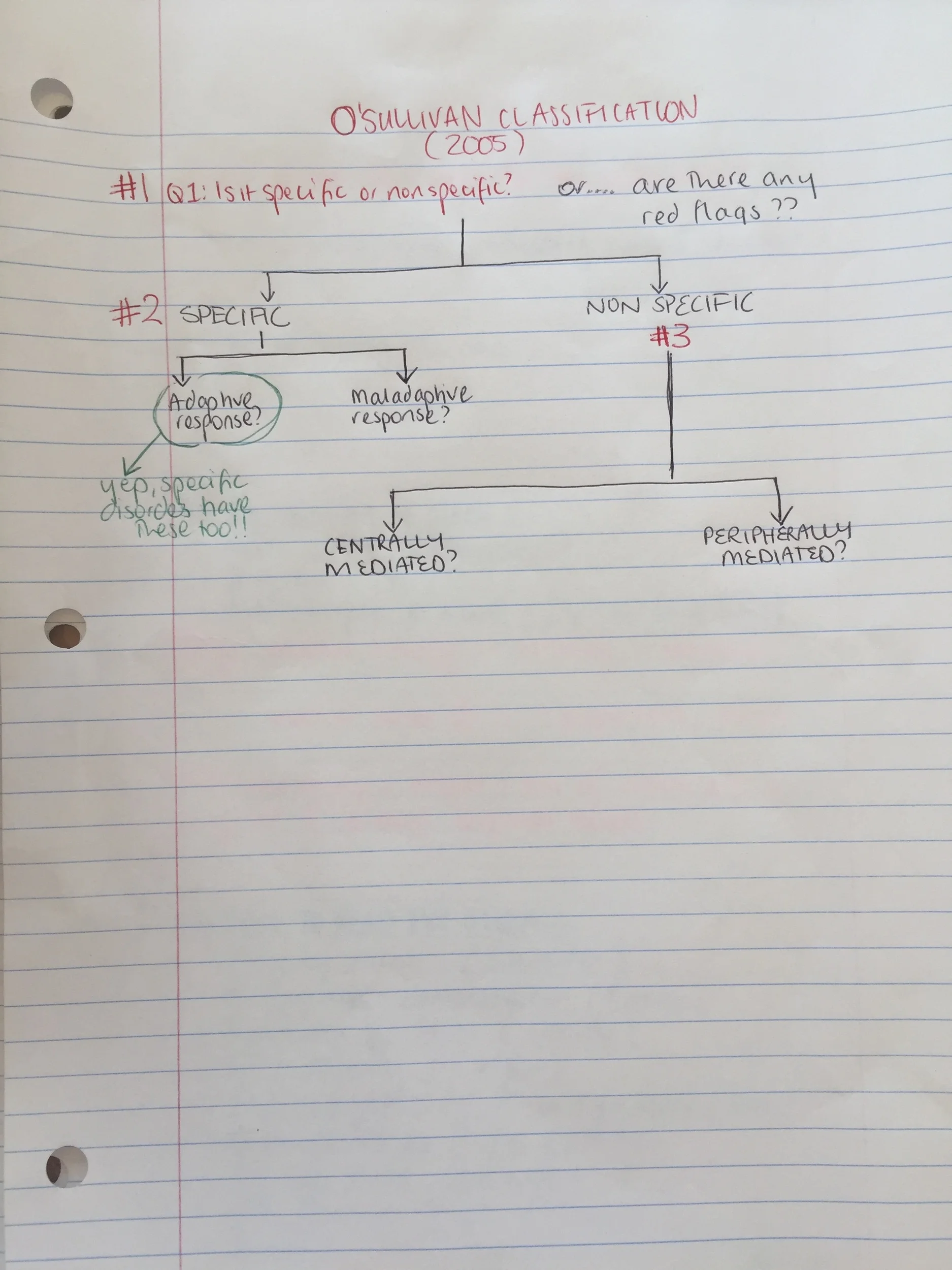

Q1 - Is the condition specific or non-specific?

Firstly you need to determine if there is a strong patho-anatomical cause that can be identified and attributed to the patient's pain. Here are some questions that need to be considered in the clinical reasoning process to help determine this.

- What is the stage of the disorder?

- Acute 1-4 weeks.

- Subacute 4-12 weeks.

- Chronic >12 weeks.

- Recurrent episodic.

- It is a specific disorder that correlates with radiological evidence? Are there any red flags?

- What is the behaviour of the pain?

- Mechanical pain is often clear, consistent, has aggs and eases and the pain is proportionate to these mechanical stimuli.

- Non-mechanical pain i.e spontaneous, constant, generalised, no clear anatomical focus, unrelated or disproportionate to mechanical behaviours, sustained response to minor triggers.

- Or is it a mixed presentation?

- Are the patient's symptoms consistent with any clinical pattern/syndrome or condition?

- What do you believe the main pain mechanism is?

- Nociceptive, Neurogenic, Central Sensitisation pain?

- Autonomic, psychological, visceral?

- Are there any psychosocial factors (Yellow Flags) present and at play?

- How does this information correlate with the information gained from outcome measures?

- Start Back Screening Tool

- OREBRO

- Roland-Morris

- Oswestry Disability Index

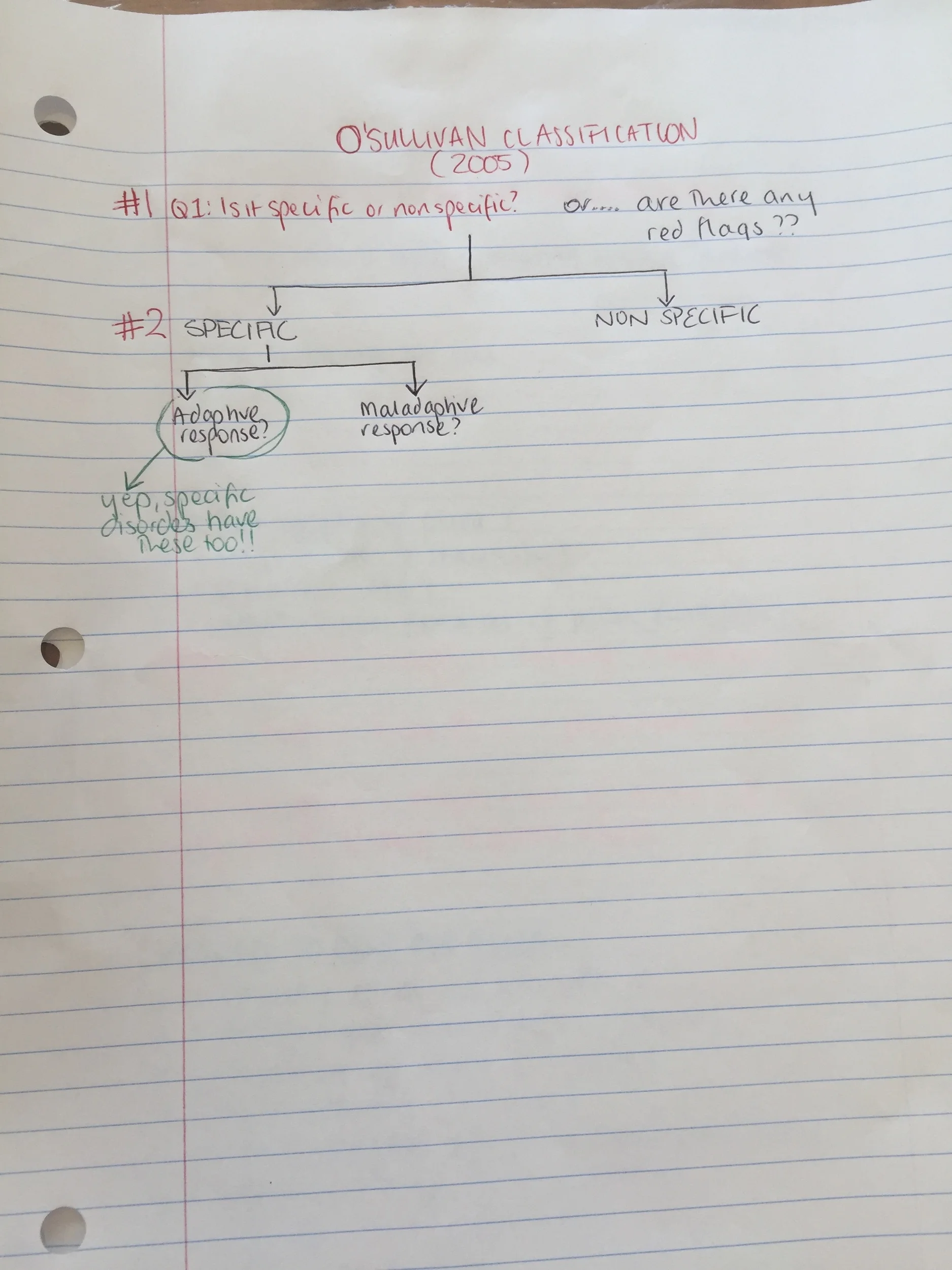

Q2 - What is the relationship between pain and movement?

Once you have determined that it is NSLBP then you need to determine if there is a relationship between pain and movement. This is found during the physical assessment as we assess posture, positioning, muscle activation patterns and functional movement patterns. Ask yourself...

Is there a relationship between the movement and pain?

Does this pattern protect or provoke their pain?

Can you change the movement pattern?

Does this help?

Without getting side-tracked on how to determine maladaptive movement patterns from protective ones (which I hope to cover next), I just want to point out that if someone has an adaptive or protective motor response or change in posture then changing or attempting to normalise this would result in deterioration of their condition or exacerbation of their symptoms.

The O'Sullivan system is a framework that aims to identify the main drivers and mechanisms of pain and dysfunction. Where movement is associated with pain, the classification considers if the movement is protective or maladaptive?

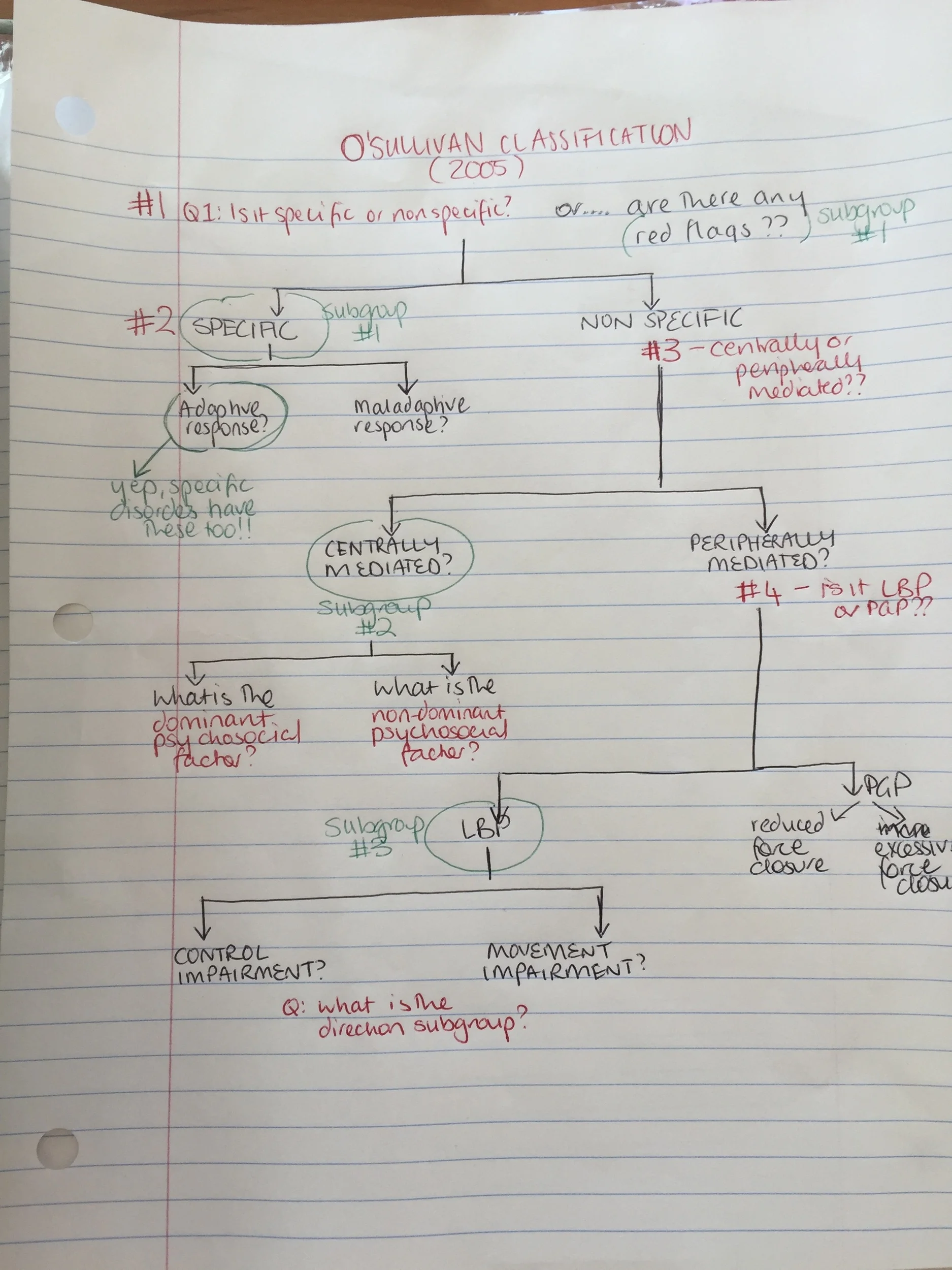

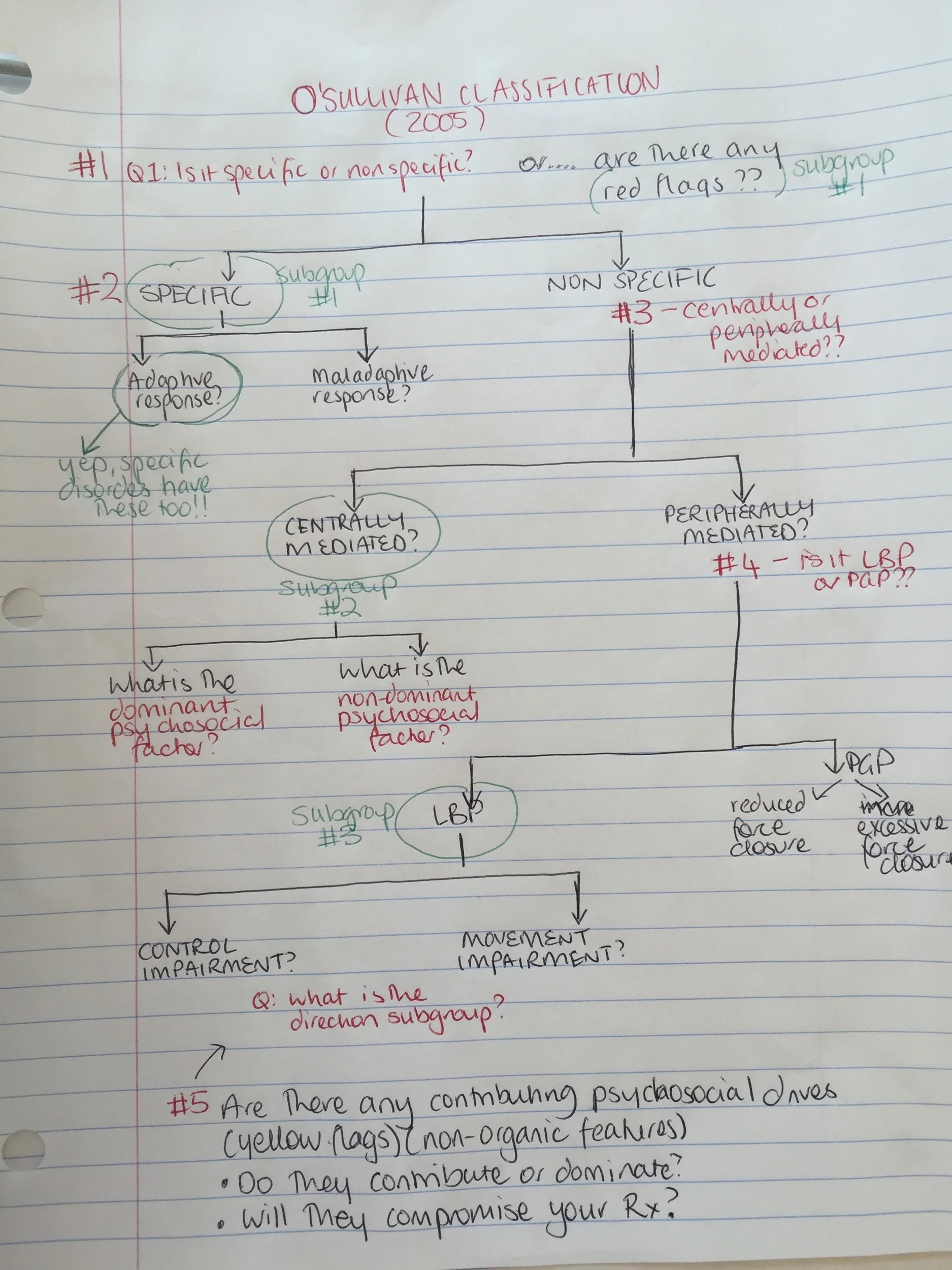

Q3 - Is it a control impairment?

Control impairments are the more common pattern and are characterised by pain provocation behaviour and named primarily in the direction of pain. Flexion pattern, active extension pattern (excessive activity resulting in loading), passive extension pattern, lateral flexion pattern and multi-direction pattern. If loading is a problem then the direction might not be as clear-cut.

With control impairments there is a loss of functional control around the neutral zone of the spinal motion segment due to specific motor control impairments. These impairments can occur at different points in movement:

- Through range movement pain - due to non-physiological motion of the spinal segment observed during dynamic tasks.

- Loading pain - due to non-physiological loading of the spinal segment observed during static loading tasks.

- End range pain - due to repetitive strain of the spinal motion segment at the end of range observed during static and dynamic functional tasks.

"The irony with these patients is that they adopt postures and movement patterns that maximally stress their pain sensitive tissue, and yet they have no awareness that they do this" (O'Sullivan, 2005, p. 9).

Their movement pattern is maladaptive and the primary driver of their pain:

- Educate your patient that you need to control the pain and desensitise the tissues.

- The rehab is not just any exercise but involved a specific motor relearning program i.e learning how to move better. If bending forward is the main painful movement then exercises will be given to help them bend forward in a better way.

- Manual therapy will have a limited role because often it won't change how they move into the painful direction.

- This approach has moved away from the previous model of 'core assessment' and is more focussed on graded functional movement retraining.

Personally, I find these patients hard to treat because usually they come in expecting a massage or spinal adjustment, and also expecting (based on past experience) that it won't help that much. Then after a full assessment I explain that I don't believe manual therapy will help them and it can be a really tough sticking point. These are the patients who I film to educate them about their movement pattern and how it is contributing to their pain.

Q 4 - is it a movement impairment?

Movement impairments are characterised with a painful loss or impairment in normal physiological movement. This category is seen with pain-avoidance behaviours. Often there are high levels of muscle guarding and co-contraction when moving into the painful direction. There is an exaggerated withdrawal motor response and high compressive loads across articular structures resulting in a rigidity and block of normal movement. This is the basis for the perpetuation of peripheral nociception. There is a strong fear and belief that the painful movement means damage is occurring and these beliefs often amplify pain. Again it is a maladaptive coping strategy that drives the pain condition.

All the muscles at play which can result in compressive loads if co-contraction occurs (Han, et al., 2011, p. 473)

They are also given a directional category of flexion, extension, side bending, rotational or multi-directional. If you can explain this to them well enough then you'll make a big difference to the way they movement. These are the goals...

- Educate them that pain doesn't equal damage.

- You have developed a faulty coping strategy for your pain.

- Restoring your movement is critical for your recovery.

- We have to desensitise your nervous system and decrease your focus on the pain.

- We have to re-expose you to the painful movement in a graded manner.

- We will use breathing, muscle relaxation techniques, postural adjustments, graded movement re-exposure and cardio exercises in your program.

Comparison of the nature of movement and control impairments (O'Sullivan, 2005, p, 248).

Q5 - what other factors could be at play?

Putting on the psychosocial hat for a little bit to consider if there are other contributing factors that aren't being peripherally mediated. Here are a few questions I used to consider during my clinical reasoning forms during Masters and they are consistent with Maitland's approach to clinical reasoning.

- Is your patient a good witness and good communicator?

- Is the interview clear and concise?

- Are they having difficulty understanding you?

- Are they withholding information from you?

- Have you taken a moment to clarify what you understand from what they are saying?

- What does the patient perceive the main problem to be?

- What do you think the main problem is?

- Is there a difference?

- If so, why and how might you need to adapt your approach to close this gap?

- What are the psychosocial contributors we need to consider?

- Beliefs - the basis of their pain, advice they have been given, strategies that have helped in the past and what future considerations are.

- Fears - regarding movement, activity, work and avoidance behaviours.

- Stress and anxiety - current levels and how stress impacts pain and how stress relates to beliefs and fears.

- Mood - what impact is this having on their life?

- Coping behaviours - Are they active copers with pacing strategies or endurance copers that just keep pushing through? What is their perceived level of control?

- Work and home - level of support, absenteeism from work, compensation.

- Comorbidity - psychological and general health.

- Lifestyle - physical activity, sleep quality & hygiene, work ergonomics, goal setting.

There are several studies which have investigated and evaluated the validity of this classification system. Clinically and personally it works really well once you know what you're looking at and it provides a great framework to explain to patients why they have a non-specific diagnosis.

Peter O'Sullivan's method has been evaluated & summarised in:

- Dankaerts, W., O’sullivan, P. B., Straker, L. M., Burnett, A. F., & Skouen, J. S. (2006). The inter-examiner reliability of a classification method for non-specific chronic low back pain patients with motor control impairment. Manual therapy, 11(1), 28-39.

- Vibe Fersum, K., O'Sullivan, P. B., Kvåle, A., & Skouen, J. S. (2009). Inter-examiner reliability of a classification system for patients with non-specific low back pain. Manual therapy, 14(5), 555-561.

IN SUMMARY...

You have to know when to pick the adaptive from the maladaptive pain behaviours.

I come back to this masterclass over and over again as I try to decipher the underlying driving pain mechanisms. When I get it right - the improvement is remarkable. When I get it wrong - I just go back to the start and begin again.

Be thorough.

Be clear.

Be honest and people will be honest with you too.

Be transparent in what you know and see and you'll improve the chances of your clients going on the journey and establishing meaningful change.

Watching Peter work on the course Cognitive Functional Approach to Management of Low Back Pain Disorders reinforced this for me, the notion that you're here to guide, to help, to decipher, and not to be a magical mystical healer. Chronic low back pain is highly prevalent and often a complex condition to treat but this classification system can help guide you towards identifying the primary driving mechanism.

Sian

Other references:

Dillingham, T. R. (1995). Evaluation and management of low back pain: an overview. SPINE-PHILADELPHIA-HANLEY AND BELFUS-, 9, 559-596.

Han, K. S., Rohlmann, A., Yang, S. J., Kim, B. S., & Lim, T. H. (2011). Spinal muscles can create compressive follower loads in the lumbar spine in a neutral standing posture. Medical engineering & physics, 33(4), 472-478.

O’Sullivan, P. (2005). Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Manual therapy, 10(4), 242-255.

O'Sullivan, P. & Lin, I. (2014). Acute low back pain. Beyond Drug Therapists. Pain Management Today, 1(1): 8-13

O’Sullivan, P. B., & Beales, D. J. (2007). Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders—Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework. Manual therapy, 12(2), 86-97.

O’Sullivan, P. B., & Beales, D. J. (2007). Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders, Part 2: illustration of the utility of a classification system via case studies. Manual Therapy, 12(2), e1-e12.

O’Sullivan, P. B. (2004). Clinical instability of the lumbar spine: its pathological basis, diagnosis and conservative management. Grieve’s Modern Manual Therapy. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 311-331.