Scapula rehabilitation - which exercise to choose?

Welcome to the third part of the shoulder impingement series, as we take a closer look at exercises for scapula control. I want to emphasise from the beginning that this blog aims is to compare and contrast rehabilitation programs for the scapula, which can be used as one component for the treatment of shoulder impingement.While the evidence to support this approach is still emerging, many Physiotherapists are trending towards including the scapula in their treatment of shoulder conditions. As a younger physiotherapist I really was overwhelmed by all the possible exercise approaches and therefore thought we could look at some of the schools of thought.

Keep in mind that the common deficits are reduced upward rotation and posterior tilt, overactivity in upper trapezius and weakness in serratus anterior. As you read through this blog you will realise that many of these exercises are familiar, but I often struggled to know the best time to use each one.

What I would love you to take away from these blogs is that:

There is a plethora of literature looking at shoulder and scapula rehabilitation programs, of which I have only skimmed the surface.

It can be difficult to decipher where to start and what exercise to choose.

Once you begin treatment, it can then be difficult to recognise the direction of the rehabilitation program.

Although these exercises may seem familiar you might not know the specifics of why they are recommended by the specialist physiotherapists below. We need to try understand the deeper knowledge that drives their clinical reasoning.

The reference list is always there if you want to delve deeper into the literature. I have and tried to select the key points that improved my understanding and helped me make sense of it all but this may not be the case for what others need to learn. So as always, if you’re looking for more don’t stop here…..

Where do we start?

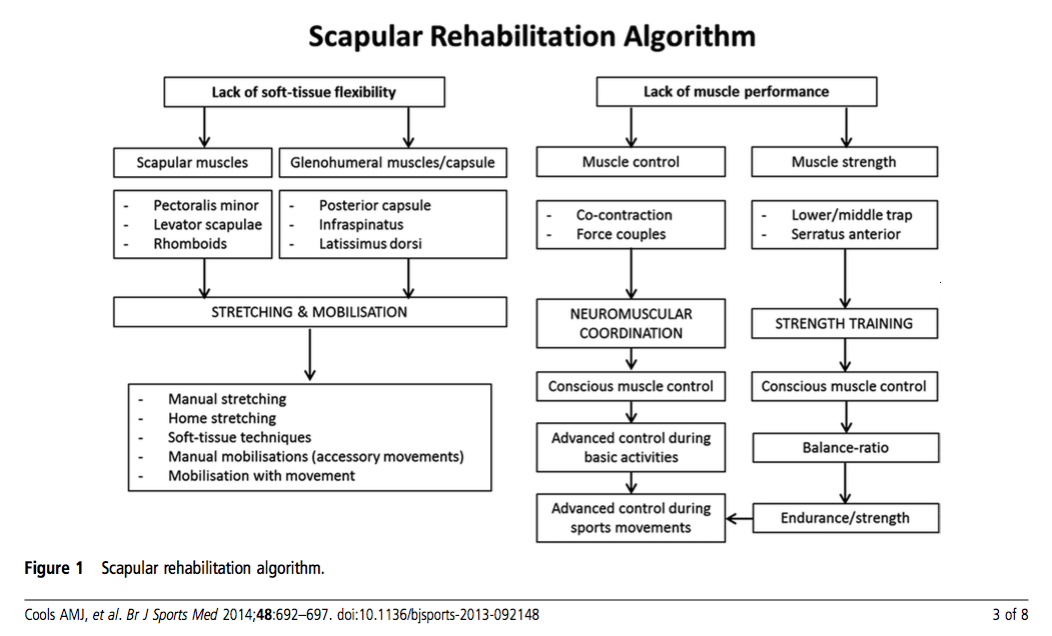

When trying to understand why scapula dyskinesis is occurring, we need to consider both the muscles that might be weak or have poor activation patterns, but also consider what soft tissue structures might have deficits in flexibility (Cools, et al., 2013).

To assist with this clinical reasoning process, Cools et al (2013) presented an algorithm which further explores how scapula rehabilitation can be incorporated into the treatment program and assist with goal setting. The authors emphasise that every patient needs to be assessed individually to determine what factors might be contributing to the problem. It is important to remember that scapula rehabilitation may only be one component of the treatment. Clinicians should also aim to restore cervical and thoracic spine mobility, lower limb kinetic chain strength and dynamic motor control and core stability.

Soft tissue flexibility issues:

As you look through the flowchart above you can see that soft tissue muscles have been sub-divided into scapular and glenohumeral muscles. Pectoralis minor tightness may result in increased scapula internal rotation and anterior tilt. A lack of glenohumeral (GH) internal rotation may indicate tightness in the GH posterior capsule and will result in increased scapula anterior tilt. Both pectoralis minor and GH posterior capsule have been quantified in studies but they are not the only muscles that can alter scapula movements (Cools, et al., 2013). Thoughts behind treatment techniques for pectoralis minor length and posterior glenohumeral capsule tightness are fairly consistent in the literature and follow these recommendations.

Pectoralis minor length:

One of the key points for the following treatment techniques is to always consider what position the shoulder has to go into for each exercise. While there may be several available stretches for pectoralis minor - not all will be suitable given the presenting pathology. When thinking of pec minor length you probably think of the door stretch with the arm in abduction and external rotation. While this is a great exercise for improving muscle length, clinically it will often put the shoulder in a position of pain, particularly with shoulder impingement. Cools et al (2013, p. 4) reviewed the current literature and found evidence to support that direct pressure on the coracoid process with the arm in little elevation (0-30 degrees forward flexion) will produce a lengthening of this muscle. The aim being to move the scapula into posterior tilt and retraction.

Posterior glenohumeral capsule tightness or post cuff tightness:

Based on their review of the literature, Cools et al (2013) suggest using the ‘sleepers stretch’ or ‘across body stretch’ and manual therapy techniques to address tightness through the back of the shoulder. Some physiotherapists have cautioned me to be careful with these stretches if there is any element of glenohumeral instability.... which just reinforces the need to have a clear idea of all the contributing factors and not just jump straight into treatment. It also reinforces that your goals for scapula rehabilitation need to match up with ones for the shoulder pathologies that might be occurring.

Lack of muscle performance:

The four most common muscle deficits commented on in the literature (Cools, et al., 2013, p.2) relating to people with shoulder impingement are:

Decreased strength in serratus anterior (SA).

Overactivity and early activation of upper trapezius (UT).

Decreased activity and delayed activation of lower (LT) and middle trapezius (MT)..

This is the part where we can start to contrast exercise prescription ideas...

There are three stages considered in the ‘Cools approach' to scapula rehabilitation.

Phase 1: Conscious muscle control.

In this phase the patient is learning to orientate their scapula. The clinician palpates the coracoid process and asks the patient to move their shoulder blade away from their finger in a backwards movement. This is combined with postural correction of the cervical and thoracic spine.

Phase 2: Muscle control & strength necessary for daily activity.

Q: Is there a timing problem?

Exercises shoulder be functionally specific to the demands of the person and therefore might vary from being open chain to closed chain. It is important to watch your patient to ensure they are carrying over the scapula positioning from phase 1.

Kibler (2008) conducted a study to look at muscle activation patters in open-chain movements and specifically looked at four exercises: low row, inferior glide, lawn mower, and robbery exercises.

Inferior glide: is an isometric exercise which can be performed in the early stages of rehabilitation to preferentially targets SA and LT, which focusses on humeral head depression and scapula retraction (Image 1).

Low row: is an isometric exercise which preferentially targets SA and LT and focusses on scapula external rotation and posterior tilt (Images 2).

Lawn Mower: is a multi-joint dynamic exercises that moves diagonally from the contralateral leg and focusses on hip and trunk extension, trunk rotation and scapula retraction, while targeting SA and LT (Image 3 & 4).

Robbery: is another dynamic exercise that uses trunk extension and bilateral scapula retraction (Image 5 & 6).

Closed chain exercises might include wall slides and push ups and your choice of exercise might be influenced by the aggravating movements for the patient, as well as the amount of pain experienced during exercise.

Push up: there are many variations of a push up i.e kneeling, a full push up position and in standing. Push ups have shown to promote SA and LT muscle activity. Interestingly, if you perform a kneeling push up and extend the same leg as the affected side, there is an increase in SA activity, compared to extending the opposite side, which promotes LT activity (Maenhout, et al., 2009).

Push up plus: the 'plus' is a component of a wall push up that helps to promote SA activity and is performed with the patient facing the wall, elbows straight and hands at 90 degrees shoulder flexion. The patient leans their body weight onto the wall and they push their body away from the wall. In images 3 & 4 below I added a push up plus into a kneeling push up but it is much easier to start on the wall.

Wall slides: are a great exercise which can help activate SA in positions of >90 degrees of elevation (Hardwick, et al., 2006). For this exercise the patient stands facing the wall with their dominant foot touching the wall and the ulnar borders of their hands on the wall and elbows bent to 90 degrees. Then they transfer their weight onto the forward foot to lean into the wall as they slide their hands up the wall into full elevation. It is important to cue patients to let their scapula slide outwards as their arms go up.

Exercises that sustain upward rotation and then promote scapula protraction, for example, the dynamic hug, wall slide, push up plus, will all have the greatest impact on serratus anterior activity (Decker, et al., 1999).

If strength is a problem:

Exercises that promote LT compared to UT include (Cools, et al., 2013; Cools, et al., 2007; Kibler, et al., 2008):

Isometric low row. A fun fact about the low row is that if you perform it balancing on the opposite leg, it further promotes LT activity.

Prone shoulder extension at 0 degrees abduction.

Side lying shoulder external rotation.

Prone shoulder abduction with external rotation (aim for more ER than in image 5 & 6).

Exercises that promote MT compared to UT include (Cools, et al., 2013; Cools, et al., 2007; Kibler, et al., 2008):

Side lying flexion.

Side lying external rotation.

Exercises that promote serratus anterior activity include (Cools, et al., 2013; Hardwick, et al., 2006; Ludewig, et al., 2004; Moseley, et al., 1992):

Push up plus (image 1).

Dynamic hug (image 2, 3 & 4).

Elbow push up (image 5).

Wall slides (image 6).

Supine punch (image 7 & 8).

While these exercises have been shown to have low UT:LT and UT:MT activity and therefore are useful in the early stages of scapula retraining when timing and activation is the goal (Cools, et al., 2007), it is important to keep in mind the importance of progressing these lying exercises into a functional (standing) position.

Phase 3: Advanced control during sporting activities.

Sport Specific

Automated movement

Kinetic chain

Diagonal and full body

"In this last stage of scapular rehabilitation, in which the treatment goal is to exercise advanced scapular muscle control and strength during sport-specific movements, special attention is given to integration of the kinetic chain into the exercise programme, implementation of sport-specific demands by performing plyometric exercises and eccentric exercises" (Cools et al, 2013, p. 5).

A recent study showed improvement in shoulder impingement following a 6 week program according to the Cools et al protocol. One of the most significant changes from the program was a reduction of upper trapezius activation which suggests a more efficient scapula recruitment pattern (Cool, et al., 2013; Cools, et al., 2007; De Mey, et al., 2012). Further studies are required to demonstrate the effect that scapula rehabilitation has on neck pain and other shoulder presentations.

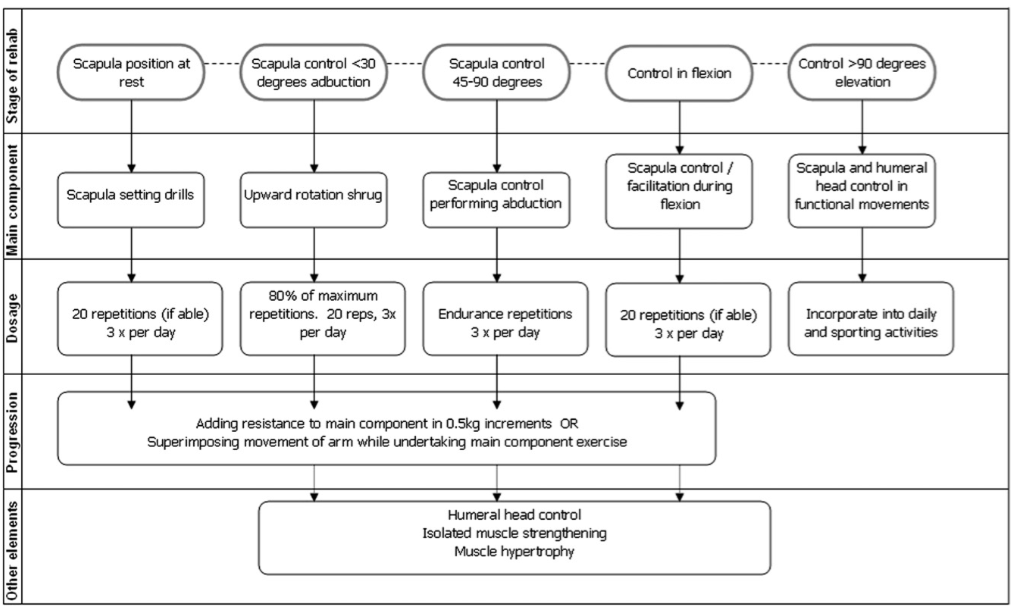

What about drooping of the shoulder?

“There has been extensive focus on the correction of scapular dyskinesis associated with weakness in the lower trapezius, however not all shoulder pathology has this type of dysfunction... While it is generally perceived that the upper trapezius is overactive or overused in many shoulder conditions, the literature is unconvincing” (Pizzari, et al., 2014). So to contrast against the approach above, Watson offers a five phased program which focusses on retraining scapula upward rotation without targeting specific muscles in isolation (Watson, et al., 2010, p. 309).

Phase 1:

The aim of the first stage is to control scapula position at rest and below 30 degrees of abduction and involves scapula setting drills. We use our knowledge of the optimal scapula position and hands-on facilitation to teach the patient about the best position.

Phase 2: Scapula control in <30 degrees of abduction

This is generally done with a upward rotation shrug but it is important to make sure the patient doesn’t move into anterior tilt or overactive their rhomboids. The dosage is 80% of maximal fatigue performed at 20 reps, 3 times a day before resistance is added. Once technique is established you can focus on endurance by adding resistance through weights or a theraband. External rotation can also be introduced in this phase to start making the exercises more functional.

One of the best ways to facilitate humeral head position and scapula setting is to place resistance to the posterior aspect of the humeral head and this is where theraband is particularly helpful in retraining movement control and proprioception. Depending what movement need focus you can first set the scapula and then use the other end of the theraband to do isolated muscle strengthening drills such as posterior deltoid (extension), supraspinatus (external rotation), subscapularis (internal rotation), upper trapezius (shrugs) and anterior deltoid (flexion). Once again, it depends on your goals for the patient.

Phase 3: Scapula control between 45-90 degrees of abduction

There are three aims for this phase:

Control of scapula position above 45 degrees of elevation.

Centralise and control humeral head position.

Load individual muscles that display weaknesses.

One thing you are looking for in these ranges is the scapula being set into the best position of upward rotation and the medial border and inferior angle being well stabilised. As you move into higher ranges of abduction it is best to think about the elbow as a lever and determine is a short lever (bent elbow) or long level is more specific to the patient. It is recommended to start with short level and progress as required. If you are looking to bulk other muscles in the shoulder you can start to bring them in at this stage of the program.

Phase 4: Moving into flexion against resistance:

Flexion comes after abduction in the rehabilitation program because winging often occurs in this position due to weakness in serratus anterior. Strengthening in abduction and external rotation are recommended first and if a serratus anterior deficit remains in flexion, control through flexion range can be commenced, while the therapist ensures that scapula control into upward rotation remains.

Phase 5: Control above 90 degrees elevation and functional-specific drills

Following the same goals as phase 3 of the Cools approach. Patients are usually discharged on a home program consisting of exercises 3-4 times per week.” (Watson, Pizari & Balster., 2010, p. 308-310).

Conclusion

When I started researching this topic, I expected there might be a suggested rehabilitation program for someone who suffered from shoulder impingement and had scapula dyskinesis. Now I realise it is definitely not that simple for the following reasons.

Shoulder impingement is not a singular diagnosis and the cause of shoulder impingement varies depending on pathology. Scapula dyskinesis is only one possible cause.

Scapula dyskinesis comes in many types depending on the predominant aberrant movement pattern and it is not specific to any particular diagnosis.

The gold standard of scapula assessment is based on clinical observation to determine what pattern of movement occurs but this doesn’t tell you what muscles might be weak, if timing issues occur, or if there are restrictions in soft tissue flexibility.

Once we have assessed the scapula and compared that to our knowledge of the normal movement, we need to consider the patient and their goals and functional demands to select the best rehabilitation protocol.

If you conclude that your patient will benefit from lower trapezius training and serratus anterior strengthening, there are a 3 stages suggested by Cools et al (2013) for promoting these muscles without over activating upper trapezius.

The approach by Watson is a great base for designing a program where retraining upward rotation is the focus.

All programs need to become function and incorporate the kinetic chain and often this takes a unilateral and diagonal approach.

Hopefully these are the messages you will also take away from the shoulder impingement and scapula rehabilitation blogs. If you have different reasoning for designing scapula programs based on preferential muscle activation, know of a series of functional exercises that are sport-specific to swimming, gymnastics or the overhead athlete, please share your comments below so that others may learn.

Sian

References:

Cools, A. M., Declercq, G., Cagnie, B., Cambier, D., & Witvrouw, E. (2008). Internal impingement in the tennis player: rehabilitation guidelines. British journal of sports medicine, 42(3), 165-171.

Cools, A. M., Dewitte, V., Lanszweert, F., Notebaert, D., Roets, A., Soetens, B., ... & Witvrouw, E. E. (2007). Rehabilitation of Scapular Muscle Balance Which Exercises to Prescribe?. The American journal of sports medicine,35(10), 1744-1751.

Cools, A. M., Struyf, F., De Mey, K., Maenhout, A., Castelein, B., & Cagnie, B. (2013). Rehabilitation of scapular dyskinesis: from the office worker to the elite overhead athlete. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2013

Decker, M. J., Hintermeister, R. A., Faber, K. J., & Hawkins, R. J. (1999). Serratus anterior muscle activity during selected rehabilitation exercises. The American journal of sports medicine, 27(6), 784-791.

De Mey, K., Cagnie, B., Van De Velde, A., Danneels, L., & Cools, A. M. (2009). Trapezius muscle timing during selected shoulder rehabilitation exercises. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 39(10), 743-752.

Hardwick, D. H., Beebe, J. A., McDonnell, M. K., & Lang, C. E. (2006). A comparison of serratus anterior muscle activation during a wall slide exercise and other traditional exercises. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 36(12), 903-910.

Uhl, T. L., Muir, T. A., & Lawson, L. (2010). Electromyographical assessment of passive, active assistive, and active shoulder rehabilitation exercises.PM&R, 2(2), 132-141.

Kibler, W. B., & McMullen, J. (2003). Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons,11(2), 142-151.

Kibler, W. B., Sciascia, A. D., Uhl, T. L., Tambay, N., & Cunningham, T. (2008). Electromyographic analysis of specific exercises for scapular control in early phases of shoulder rehabilitation. The American journal of sports medicine, 36(9), 1789-1798.

Maenhout, A., Van Praet, K., Pizzi, L., Van Herzeele, M., & Cools, A. (2009). Electromyographic analysis of knee push up plus variations: what’s the influence of the kinetic chain on scapular muscle activity?. British journal of sports medicine.

Moseley, J. B., Jobe, F. W., Pink, M., Perry, J., & Tibone, J. (1992). EMG analysis of the scapular muscles during a shoulder rehabilitation program.The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 20(2), 128-134.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome part 2: conservative management of thoracic outlet. Manual therapy, 15(4), 305-314.