Does barefoot running reduce the risk of injury?

Barefoot running is a topic that has gained a huge amount of popularity in the media among scientists, clinicians and mostly, runners.

It has been proposed that humans have evolved to be able to adopt a barefoot running style, and that these changes in biomechanics will reduce impact peaks, increase proprioception and foot strength and therefore reduce risk on injury. However it may not be this simple.

"There remains a lack of conclusive evidence proving or refuting the proposed advantages of barefoot running" (Tam, Wilson, Noakes & Tucker, 2013, p.349).

Tam et al (2013) provided an evaluation of the current evidence regarding the effect of barefoot and shod (shoe) running on lower limb injuries. These are the main points I took from reading the article.

- Barefoot running has the potential to reduce tibial stress fractures but increase risk of metatarsal stress fractures.

- Barefoot running may reduce the risk of developing patellofemoral joint pain but increase the risk of developing achilles tendinopathy. It may also decrease the risk of plantar fasciitis. But it is not as clear cut as that.

- It depends largely on the biomechanics of running more than the footwear we run in.

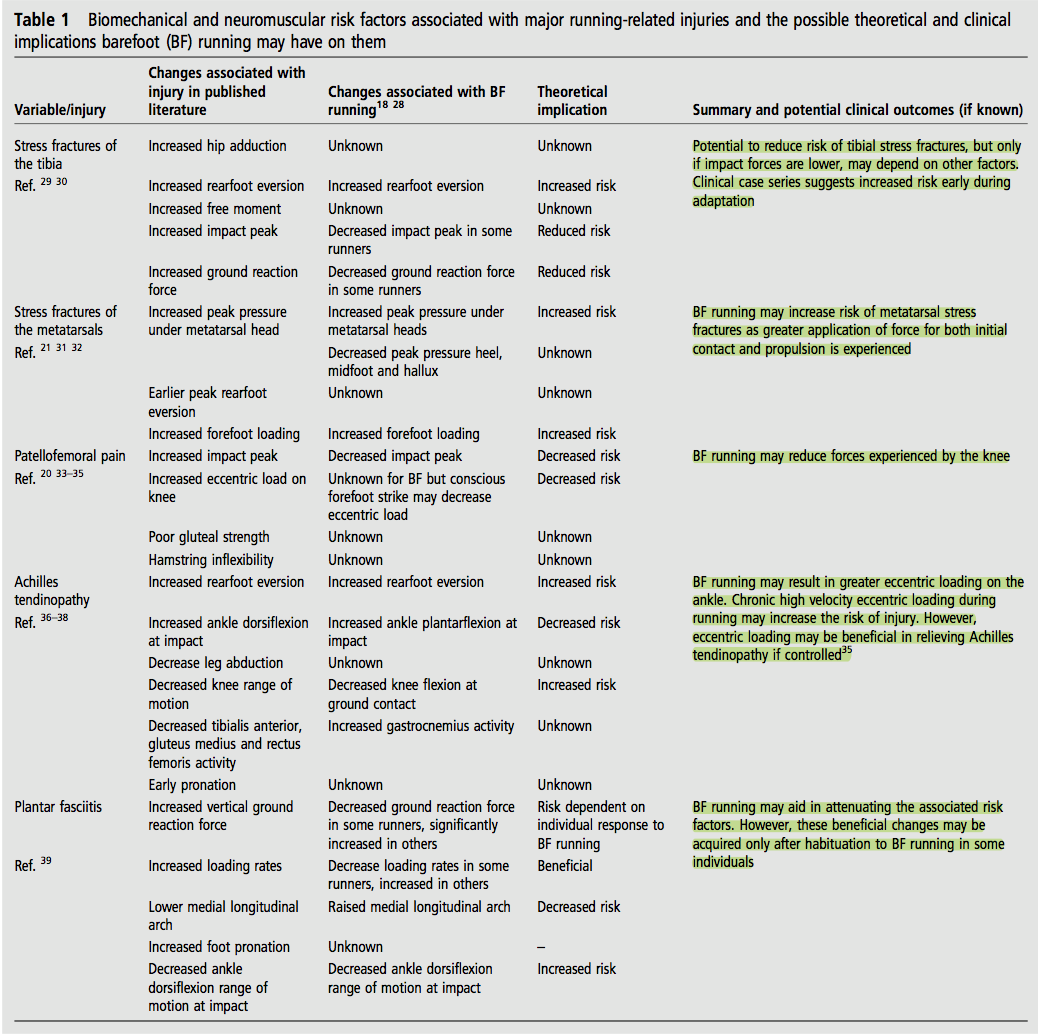

- The table below explains this research further and a summary follows with the current evidence we know about barefoot and shod running.

(Tam, Wilson, Noakes & Tucker, 2013, p. 451)

Evolution - gait pattern is more important that footwear.

There is no current evidence to say that shoe technology has changed the running-related injury rate over time (Tam, Wilson, Noakes, & Tucker, 2013, p. 350). This may be due to training volumes and that some people who run are not physically capable of running safely. Nonetheless, injury aetiology is far more complex than simply the gait pattern and the footwear we use and requires further investigation is required to fully understand how we can reduce injury risk.

Biomechanics & Foot strike - heel striking is associated with increased risk of injuries but not all barefoot runners adopt a forefoot strike pattern.

It is well accepted that heel strike during landing is associated with increased risk of lower limb injuries (not all injuries as seen in the table above) and therefore a forefoot strike pattern is assumed to be superior. However not all runners adopt a forefoot strike pattern when transitioning to barefoot running.

Up to 72% of barefoot runners heel strike at comfortable running speeds, however as speed increases most shift to a forefoot pattern. Up to 40% of runners however, remain heel strikers even as speed increases (Tam, Wilson, Noakes, & Tucker, 2013, p.351).

Lower limb - stress fractures result from increased ground reaction forces.

Generally there is an increased risk of developing stress fractures in the 2nd and 3rd metatarsals with the transition to barefoot running, as a result of direct loads through the fore foot on impact.

On the opposite side of the coin, if a heel strike pattern is used then calcaneal or tibial stress fractures can also occur.

Therefore it is safe to assume that ground reaction forces need to be sufficiently controlled to reduce injury risk. This comes from intrinsic factors such as joint biomechanics and neuromuscular control.

Ankle - there are higher demands on the ankle joint and calf muscle with forefoot striking.

Barefoot running requires increased ankle plantar flexion and eccentric calf activity on impact, which may increase the risk of developing ankle injuries, calf strains or achilles tendinopathy.

When making the transition to a forefoot strike pattern, you need both ankle dorsiflexion range, calf length and calf strength to safely adopt the new technique.

Knee - forefoot striking is associated with reduced eccentric loading of the knee.

Barefoot running is associated with increased knee flexion prior to landing, shorter stride length, and increased step frequency. This increased knee flexion is associated with reduced eccentric loading prior to landing, having a positive impact on knee injuries especially patellofemoral joint pain.

Also remember that gluteal muscular control has been associated with patellofemoral joint pain and therefore this too should be considered and assessed as a component of the overall gait pattern. Gluteal muscle control was not a component of this literature review.

Skill acquisition of barefoot running - some individuals may be incapable of achieving a barefoot running technique and the associated biomechanical benefits.

"83% of shod runners will continue to heel strike which results in the rate of loading being 700% greater" (Lieberman, et al, 2010). Thats a serious statistic!

Some will adopt the strike pattern instantly and therefore benefit from the changes associated with this pattern. Some will take weeks to make the transition and need careful training and advice to avoid overuse, and others just may never make the transition. For those who don't, running barefoot will expose them to much higher risks of injury.

Fatigue - fatigue increases the risk of injury due to reduced/altered control of ground reaction forces.

Running is a sport that involves a huge amount of repetitive movements. It is the accumulation of load that leads to overuse injury. As muscle fatigue alters patterns of ground reaction forces, it may also influence lower extremity injuries.

Training intervals and distances should be considered in the early phase of adaptation to avoid overuse and fatigue.

Performance - shoe mass prevails over the cushioning effect.

Performance refers most often to running economy. So the question should be asked "Does the construction and weight of the shoe alter running economy?" There is no current study that compares barefoot, minimalist shoe, lightweight and cushioned shoes. There is some evidence however that shows that reduced shoe mass has a positive impact on lower limb biomechanics and running economy. The best footwear still needs to be investigated and will depend largely on patient characteristics and running gait patterns.

Conclusion

The evidence is still limited but it is clear to say that barefoot running is not better for everyone in reducing lower limb injuries. And, if applied to the wrong person, may increase their injury risk significantly. But that comes down to a bit of common sense and knowing it is not as simple as barefoot running versus shod running. There is a large grey area that exists between the two forms of running. Advice can only really given following an assessment of the patient and their ability to adapt to the changes required.

Sian

References

Lieberman, D. E., Venkadesan, M., Werbel, W. A., Daoud, A. I., D’Andrea, S., Davis, I. S., ... & Pitsiladis, Y. (2010). Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature, 463 (7280), 531-535.

Tam, N., Wilson, J. L. A., Noakes, T. D., & Tucker, R. (2013). Barefoot running: an evaluation of current hypothesis, future research and clinical applications. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2013.