Treating Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) by addressing fear and anxiety

I am currently undertaking my Musculoskeletal Specialisation program, which is a two year program focusing on improving our clinical reasoning, assessment and management skills when treating musculoskeletal conditions. While COVID-19 has affected our face-to-face capacity, the program has given me a lot of motivation to continue improving my own skills, but also in continuing to progress the knowledge of all physio’s. Technology and research is changing so quickly, so we need to keep sharing our new knowledge and always being open to learning!

The following case study, a requirement of the program, gave me the opportunity to delve into the CRPS literature and give me a greater understanding of psychosocial contributors to pain, and how to manage them. This was just published in the Australian Physiotherapy Association’s InTouch magazine, so can now be shared!

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a condition which presents with a severe pain experience disproportionate to an inciting event, accompanied by various changes to sensory, autonomic, motor and immune systems (Pons et al., 2015). Symptoms are often localised to a distal limb and can be associated with altered spatial awareness and bodily neglect (Goebel et al., 2019). While most patients experience improvement in symptoms, 95% continue to experience symptoms at one year (Bean, Johnson, Heiss-Dunlop, & Kydd, 2016), creating significant personal, financial and social burden (Goebel et al., 2019).

Diagnosis is based on the “Budapest criteria” (Harden et al., 2010), and differentiated into CRPS Type I, without nerve lesion, and CRPS Type II, with confirmed nerve lesion (Birklein & Dimova, 2017) (See Image 2). It is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring the ruling out of differential inflammatory, vascular and neuropathic causes (Harden et al., 2010).

Reasons for developing CRPS remain inconclusive, however being female, sustaining a distal radius or intra-articular ankle fracture (Pons et al., 2015), and reporting greater than 5/10 pain in the first week following trauma (Moseley et al., 2014) have been identified as the strongest risk factors. Anxiety and immobilisation are weaker risk factors (Pons et al., 2015).

Previous life stressors are relevant, with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) present in 38 percent of individuals with CRPS (Speck et al., 2017). While 14 percent reported PTSD due to the onset of CRPS, the rest reported suffering PTSD secondary to one or multiple traumatic life events, such as domestic violence, sexual abuse in childhood, war experience and severe accident (Speck et al., 2017). The diagnosis and symptoms of CRPS were perceived as an additional trauma in 38 percent of those who suffered PTSD prior to CRPS onset (Speck et al., 2017).

Although psychosocial factors are not considered risk factors for CRPS onset, the presence of pain-related fear, anxiety and high perceived disability at diagnosis predicted poorer outcomes at one year (Bean et al., 2015). Psychological distress and poor expectations of recovery are predictors in “persisting limb pain” and poor return to work prognosis (Birklein & Dimova, 2017), but have not yet been associated with CRPS.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old female was referred for physiotherapy by her general practitioner (GP), with a diagnosis of left ankle CRPS. An inversion injury of her left ankle 11 weeks prior had generated 8/10 intensity lateral ankle pain using the numerical rating scale (NRS), with imaging confirming an avulsion fracture of the lateral malleolus. She was placed in an immobilisation boot and instructed to remove it after four weeks and attempt ambulation, but to continue to wear if weight-bearing remained painful.

At eight weeks post-fracture, unhappy with her progress, the patient called the fracture clinic and was referred for orthopaedic review and MRI. The surgeon diagnosed CRPS and returned her for GP management, with surgery an option ‘if it doesn’t get better’.

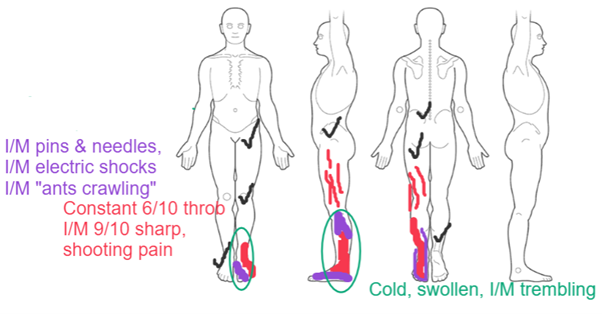

Figure 1. Body Chart at Initial Assessment.

The patient presented ambulating with two elbow crutches and moonboot, reporting constant 6/10 throbbing with intermittent (I/M) sharp, shooting 9/10 pain from the distal ankle to lateral knee. She reported paraesthesia under the foot, as well as feelings of ‘ants crawling’ and ‘electric shocks’ in the toes and lateral lower leg. Her lower limb felt cold and stiff and appeared ‘purple and blotchy’. The patient was unable to have blankets resting on her leg, as the pressure created severe shooting pain, and she reported difficulty wearing socks as it ‘strangled and squeezed’ her ankle.

Walking created immediate 8/10 constant throbbing pain, with walking on uneven ground reproducing ‘agony up her leg’. This pain took varying times to settle, sometimes reducing to 6/10 on rest while other times remaining throughout the night. She correlated increased frequency of feeling ‘electric shocks’ with increased stress levels, and she reported not trusting her leg, and requiring the moonboot for fear of doing further damage.

She believed the fracture hadn’t healed, as otherwise her ankle would be pain-free, and she was concerned weight-bearing would further delay healing. Her goals were to receive a diagnosis, understand her pathology and receive a management plan for recovery.

The patient reported waking up to five times a night, due to both pain and insomnia, and being awake for 1-2 hours on waking. She suffered clinical anxiety, controlled with exercise and regular psychology consultations, and had undergone a gastric bypass four years earlier, but was otherwise well. She was prescribed Naproxen and Panadeine Forte five days earlier, which had no effect on her pain, but possibly assisted sleep. She took no other medication.

The patient lived at home with her husband and three children, but had requested a divorce seven months earlier as she identified as lesbian. She worked full-time in a senior position at the local school. She described the four months prior to her ankle injury as extremely stressful and confronting, which prompted her to initiate fortnightly psychology consultations.

Examination Findings

On examination, the patient’s left lower limb appeared swollen, discoloured and cold to touch, compared to right. In standing and while transferring from chair to plinth, she was observed to avoid weight-bearing on the left lower limb.

Sensory testing with light tissue touch revealed tactile hyperaesthesia over the navicular, as well as 5/10 pain over the lateral foot, ankle and fibula. Cold sensitivity testing with ice cube (Zhu et al 2019) reproduced 8/10 coldness and 6/10 throbbing ache over the lateral foot, compared to 3/10 coldness on the right. Both light touch and cold sensitivity testing reproduced focal allodynia over the lateral malleolus and hyperalgesia along the fibula, in a non-dermatomal pattern. Reflex testing was normal. Nerve palpation along the fibular nerve reproduced 4/10 local pain proximally, increasing to 8/10 shooting pain around the lateral malleolus.

Left/right discrimination testing, using the NOI Recognise Foot application, showed 90 per cent accuracy bilaterally, and 1.1 seconds on left compared to 1.2 seconds on the right. Two point discrimination showed 45mm on the left foot, while 4mm on the right. Mirror-box testing of right ankle movements, with the left remaining still, reproduced left foot tingling and 4/10 shooting pain (Acerra & Moseley 2005). Imagining inversion of the left ankle caused 5/10 shooting pain, and breath-holding.

All active left ankle movements and big toe extension were grossly restricted, with passive movement restricted by apprehension and shooting pain. Ankle inversion was most provocative, with ~1˚ reproducing 7/10 shooting pain and severe apprehension.

Left straight leg raise was limited to 40˚ (compared to 80˚ on the right), reproducing foot and ankle 6/10 shooting pain, which increased with cervical flexion. Anterior drawer and talar tilt testing showed mild laxity globally, with no increase in symptoms. Interestingly, active and imagined left inversion reproduced severe pain, while passive talar tilt did not aggravate symptoms. Lumbar movement testing and palpation findings detected no abnormality.

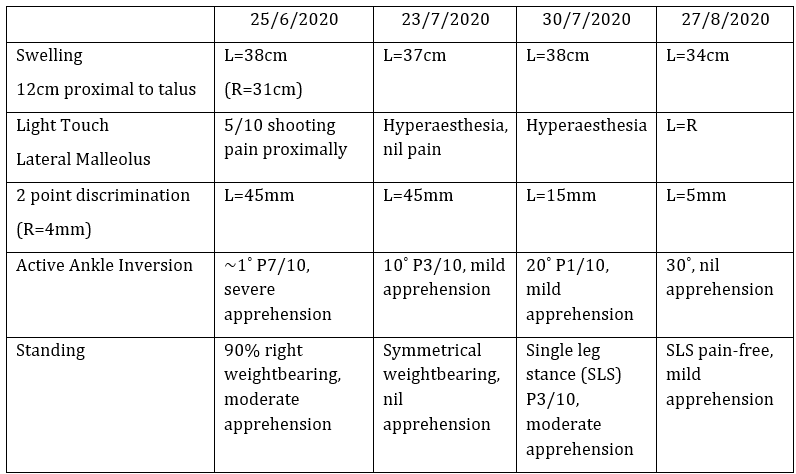

Table 1. Key Assessment Findings and Reassessment Measures.

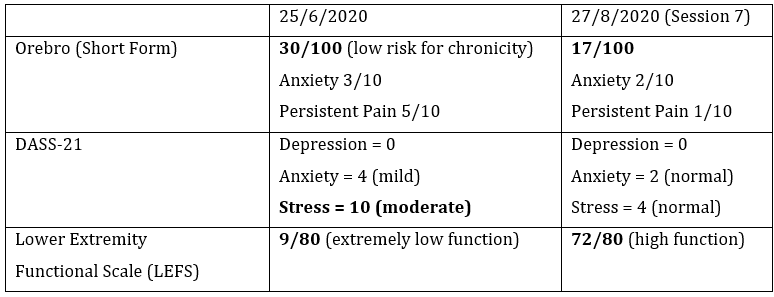

Screening tests were administered (see Table 2), indicating moderate stress levels (Henry & Crawford 2005) and severe functional disability (Binkley et al 1999) but predicting low risk of developing chronicity (Linton et al 2011).

Table 2. Screening Questionnaire & Outcome Measure Key Findings.

Ankle imaging showed a grade II sprain of calcaneofibular ligament with an associated small avulsion fracture of the fibular head (believed to be a reporting error, instead meaning lateral malleolus) and generalised osteopenia.

Following assessment, the patient was diagnosed with CRPS Type 1 (Harden et al 2010), secondary to a lateral malleolus avulsion fracture (see Image 2). It is difficult to exclude peroneal neuropathy, as straight leg raise and nerve palpation were positive, and peroneal bias was unable to be performed due to extreme pain on inversion. Given the non-dermatomal sensory and motor changes, peroneal neuropathy appears less likely in this case, but cannot be excluded.

While osteoporosis can cause foot swelling and pain on walking, and osteopenia is present on imaging, it is unlikely to cause this severity of symptoms. It is more likely that the osteopenia occurred secondary to eleven weeks of left lower limb immobilisation. Imaging excluded malignancy, infection and soft tissue injury. Symptoms are inconsistent with rheumatoid arthritis, Raynaud’s syndrome, compartment syndrome and arterial or venous insufficiency.

Image 2. Budapest Criteria for CRPS Diagnosis [6], with patient’s signs and symptoms highlighted.

Treatment

Disability associated with CRPS Type 1 is directly related to pain-related fear and higher anxiety (Geha et al., 2008), with avoidance behaviours and catastrophising resulting in withdrawal of activities of daily living and reduced quality of life (QOL). A biopsychosocial treatment approach was adopted (O'Connell, Wand, McAuley, Marston, & Moseley, 2013), incorporating fear-reducing techniques and graded exposure to painful activities (Vlaeyen, Crombez, & Linton, 2016), to address pain-related fear and anxiety.

Imaging findings were discussed, with reassurance that the fracture had healed, surgery is an unlikely option for her condition (Birklein & Dimova, 2017) and that CRPS is not visible on MRI (Agten et al., 2020). Visualising the fracture size, correlating it to “the size of a lentil”, visibly normalised the patient’s breathing pattern and reduced resting muscle tension. The diagnosis of CRPS was discussed, with explanation regarding pain sensitivity and pain severity not correlating to tissue damage (Moseley, 2003).

Sleep was identified as a modifiable central modulator (Sivertsen et al., 2015), and neuropathic pain medications discussed, with Amitriptyline suggested for it’s secondary effect on sleep and anxiety (Birklein & Dimova, 2017). The patient was hesitant to trial neuropathic pain medications, so in consultation with the GP utilised 25mg Phenergen as a sleeping agent. Cessation of Naproxyn and Panadeine Forte was encouraged, as minimal benefit was reported and harmful side effects were likely (Mathieson, Lin, Underwood, & Eldabe, 2020), particularly following gastric surgery. After seven nights of Phenergen, the patient reported sleeping six to eight hours nightly, and pain reduction to a constant 4/10 pain.

A graded exposure approach was utilised (den Hollander et al., 2016), beginning with mirror-box therapy and ankle dorsiflexion/plantarflexion and eversion movements. Following this “ankle series”, light touch and cold sensation felt equal to the unaffected side. The patient was to resume boot camp, substituting any ‘painful’ lower limb activities with her “ankle series”, aiming to facilitate pain reduction through exercise induced analgesia (Daenen, Varkey, Kellmann, & Nijs, 2015), and improved sleep quality (Rubio-Arias, Marin-Cascales, Ramos-Campo, Hernandez, & Perez-Lopez, 2017).

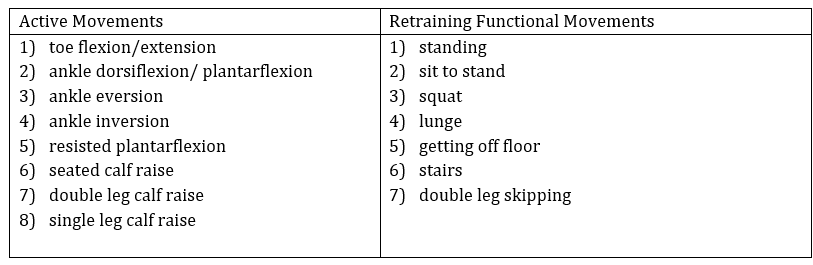

Although having returned to boot camp, the patient avoided any exercises on the ground, as she returned to standing by completing a right single leg burpee-type movement. She avoided any left leg weight-bearing, reporting a perceived exertion of 8/10. Retraining prone to standing, using a two-point knee to left half-kneel to standing approach, resulted in a pain-free movement with 1/10 perceived exertion. Functional retraining incorporating diaphragmatic breathing, to prevent breath-holding and abdominal bracing, and encouraging left weight bearing provided the patient with an active strategy for pain modulation, reducing fear and anxiety (Vlaeyen et al., 2016). Progression of additional functional movements and exercises are described below (see Table 3).

Functional movement retraining began on follow-up, incorporating diaphragmatic breathing into functional tasks, to prevent breath-holding and abdominal bracing, and encouraging left weight bearing. This provided the patient with an active strategy for pain modulation, reducing fear and anxiety (Vlaeyen et al 2016). Although having returned to boot camp, the patient got off the ground by completing a single leg burpee-type movement, avoiding left weight bearing, with a reported perceived exertion of 8/10. Retraining, using a two-point kneel to left half-kneel to standing approach resulted in a pain-free movement with a 1/10 perceived exertion. Progression of additional functional movements and exercises are described below (see Table 3.).

Table 3. Graded Exposure Approach showing Exercise Progressions

The patient reported drastically increased “electric shocks” on the fourth consultation, following heightened stress levels on returning to work after holidays. This aggravation initiated further consultation with the GP, where 75mg Gabapentin was prescribed. Although Amitriptyline was recommended as a first line neuropathic medication, Gabapentin has shown moderate effect in reducing allodynia (van de Vusse, Stomp-van den Berg, Kessels, & Weber, 2004), and was preferred by the GP. Allodynia and spontaneous shooting pains subsided within three days, with two point discrimination reducing to 15mm (from 45mm).

During the fifth consultation, after establishing a strong therapeutic alliance, the patient felt comfortable disclosing the events which prompted psychology intervention. Four months prior to her ankle injury, the patient experienced previously repressed flashbacks of childhood sexual. This led to acknowledgment of her sexuality, and initiated divorce proceedings. Education was provided regarding childhood trauma and widespread pain, and the correlation between PTSD and CRPS (Generaal et al., 2016; Speck et al., 2017). The patient reported “relief” that the CRPS “is not my fault” and reduced anxiety levels following this discussion.

The patient attended seven consultations in nine weeks, reporting 90 percent improvement, with future treatment focused on returning to running and burpees.

Discussion

Although the Orebro result indicated low risk for chronicity, multiple psychosocial risk factors were identified clinically, including anxiety, pain-related fear and avoidance behaviours. Given pain-related fear and anxiety were the biggest predictors of persistent disability (Bean et al., 2015), a biopsychosocial management approach was adopted.

Graded exposure therapy has shown good efficacy in reducing pain, catastrophising and disability, while increasing QOL in CRPS (den Hollander et al., 2016). A graded exposure approach, addressing left lower limb weightbearing and function, was effective in reducing pain-related fear and modifying unhelpful protective behaviours (O'Connell et al., 2013; Vlaeyen et al., 2016). Diaphragmatic breathing has been shown to provide an analgesic effect, while reducing cortisol and stress levels (Chalaye, Goffaux, Lafrenaye, & Marchand, 2009; Ma et al., 2017), so was incorporated into functional tasks to further reduce fear on movement.

Mirror-box therapy was trialled to address the gross difference in left foot two-point discrimination, and dysynchiria (Acerra & Moseley, 2005). While there is evidence mirror-box therapy and graded motor imagery are effective in management of acute CRPS (Goebel et al., 2019; O'Connell et al., 2013), this increased the patient’s symptoms. Possibly the unaffected left/right discrimination indicated the patient had progressed past graded motor imagery techniques or possibly the mirror-box increased apprehension, resulting in a heightened pain response. While helpful diagnostically to confirm central mediation, it was ineffective as a treatment modality, so was ceased.

Current guidelines recommend CRPS patients be prescribed appropriate pharmacological pain management, including neuropathic pain medications, although acknowledge medications may be ineffective and cause adverse side effects (Goebel et al., 2019). In hindsight, earlier prescription of Gabapentin may have hastened recovery, as pain and allodynia drastically reduced after three days of consumption. However, due to the lack of consistent evidence (Mathieson et al., 2020; van de Vusse et al., 2004), potential gastrointestinal complications, and continued improvements achieved through conservative management, delayed medication prescription was decided. Actively modifying her pain levels reinforced the belief that pain does not equal tissue damage (Moseley, 2003), which lowered her pain-related fear.

Although unaware of the link between PTSD and CRPS prior to assessment, various other psychosocial factors with links to persistent pain were identified. Additionally, sexual minorities experience greater frequency of chronic pain than heterosexuals (Katz-Wise et al., 2015). Initially, anxiety, high stress levels and poor sleep, secondary to publicly acknowledging her sexuality and subsequent marriage breakdown, was believed to have contributed to the patient developing CRPS. Later discussion uncovered a history of childhood trauma, sexual abuse and PTSD symptoms.

Childhood trauma and sexual orientation are predictive of persistent, widespread pain (Generaal et al., 2016; Katz-Wise et al., 2015), however PTSD is identified as a strong risk factor for CRPS onset (Speck et al., 2017). Although the patient’s childhood trauma and subsequent PTSD did not alter management, it added to the clinical picture and the patient’s understanding of the condition. An Impact of Events Scale will now be routinely completed by patients presenting with CRPS-like symptoms. This may assist in detection of PTSD, recognition of additional contributing factors and facilitate further psychological referral, if warranted.

This patient displayed multiple psychosocial factors and behaviours which contribute to persistent pain, including poor sleep, anxiety, high pain at time of injury, pain-related fear, avoidant behaviours, sexual orientation, childhood trauma and PTSD (Bean et al., 2015; Generaal et al., 2016; Katz-Wise et al., 2015; Moseley et al., 2014; Sivertsen et al., 2015; Speck et al., 2017; Vlaeyen et al., 2016). Although questionnaires were used, a thorough clinical examination assessing psychosocial factors and observing avoidant behaviours was more effective in detecting these factors, reinforcing the need to effectively communicate and build rapport with the patient. By addressing the patient’s goals of receiving a diagnosis and effective management plan, a strong therapeutic alliance was built. It is believed this enabled the patient to divulge her sexual orientation, history of sexual abuse, and subsequent PTSD.

Conclusion

While risk factors and treatment of CRPS remain inconclusive, the literature clearly identifies that pain-related fear and anxiety predict disability (Bean et al., 2015; Birklein & Dimova, 2017; Pons et al., 2015). Using a graded exposure approach, and providing strategies to modify unhelpful movements, and addressing modifiable central modulators, allowed to patient to achieve 90% recovery within seven sessions. This case study highlights the importance of recognising and addressing pain-related fear and modifying avoidant behaviours to facilitate recovery.

Alicia

References

Acerra, N. E., & Moseley, G. L. (2005). Dysynchiria: Watching the mirror image of the unaffected limb elicits pain on the affected side. Neurology, 65(5), 751-753.

Agten, C. A., Kobe, A., Barnaure, I., Galley, J., Pfirrmann, C. W., & Brunner, F. (2020). MRI of complex regional pain syndrome in the foot. European Journal of Radiology, 129.

Bean, D. J., Johnson, M. H., Heiss-Dunlop, W., & Kydd, R. R. (2016). Extent of recovery in the first 12 months of complex regional pain syndrome type-1: A prospective study. European Journal of Pain, 20(6), 884-894.

Bean, D. J., Johnson, M. H., Heiss-Dunlop, W., Lee, A. C., & Kydd, R. R. (2015). Do psychological factors influence recovery from complex regional pain syndrome type 1? A prospective study. Pain, 156(11), 2310-2318.

Binkley, J. M., Stratford, P. W., Lott, S. A., & Riddle, D. L. (1999). The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): Scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Physical Therapy, 79(4), 371-383.

Birklein, F., & Dimova, V. (2017). Complex regional pain syndrome-up-to-date. Pain reports, 2(6), e624-e624.

Chalaye, P., Goffaux, P., Lafrenaye, S., & Marchand, S. (2009). Respiratory Effects on Experimental Heat Pain and Cardiac Activity. Pain Medicine, 10(8), 1334-1340.

Daenen, L., Varkey, E., Kellmann, M., & Nijs, J. (2015). Exercise, Not to Exercise, or How to Exercise in Patients With Chronic Pain? Applying Science to Practice. Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(2), 108-114.

den Hollander, M., Goossens, M., de Jong, J., Ruijgrok, J., Oosterhof, J., Onghena, P., . . . Vlaeyen, J. W. S. (2016). Expose or protect? A randomized controlled trial of exposure in vivo vs pain-contingent treatment as usual in patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1. Pain, 157(10), 2318-2329.

Geha, P. Y., Baliki, M. N., Harden, R. N., Bauer, W. R., Parrish, T. B., & Apkarian, A. V. (2008). The Brain in Chronic CRPS Pain: Abnormal Gray-White Matter Interactions in Emotional and Autonomic Regions. Neuron, 60(4), 570-581.

Generaal, E., Milaneschi, Y., Jansen, R., Elzinga, B. M., Dekker, J., & Penninx, B. (2016). The brain-derived neurotrophic factor pathway, life stress, and chronic multi-site musculoskeletal pain. Molecular Pain, 12.

Goebel, A., Barker, C., Birklein, F., Brunner, F., Casale, R., Eccleston, C., . . . Wells, C. (2019). Standards for the diagnosis and management of complex regional pain syndrome: Results of a European Pain Federation task force. European Journal of Pain, 23(4), 641-651.

Harden, R. N., Bruehl, S., Perez, R., Birklein, F., Marinus, J., Maihofner, C., . . . Vatine, J. J. (2010). Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the "Budapest Criteria") for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain, 150(2), 268-274.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227-239.

Katz-Wise, S. L., Everett, B., Scherer, E. A., Gooding, H. C., Milliren, C. E., Austin, S. B., & (2015). Factors associated with sexual orientation and gender disparities in chronic pain among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Preventive Medicine Reports, 2(2015), 765-772.

Linton, S. J., Nicholas, M., & MacDonald, S. (2011). Development of a Short Form of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Spine, 36(22), 1891-1895.

Ma, X., Yue, Z. Q., Gong, Z. Q., Zhang, H., Duan, N. Y., Shi, Y. T., . . . Li, Y. F. (2017). The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress in Healthy Adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(874).

Mathieson, S., Lin, C. W. C., Underwood, M., & Eldabe, S. (2020). Pregabalin and gabapentin for pain. Bmj-British Medical Journal, 369.

Moseley, G. L. (2003). A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy, 8(3), 130-140.

Moseley, G. L., Herbert, R. D., Parsons, T., Lucas, S., Van Hilten, J. J., & Marinus, J. (2014). Intense Pain Soon After Wrist Fracture Strongly Predicts Who Will Develop Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Pain, 15(1), 16-23.

O'Connell, N. E., Wand, B. M., McAuley, J., Marston, L., & Moseley, G. L. (2013). Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(4).

Pons, T., Shipton, E. A., Williman, J., & Mulder, R. T. (2015). Potential Risk Factors for the Onset of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1: A Systematic Literature Review. Anesthesiology Research and Practice, 2015. Retrieved from <Go to ISI>://WOS:000363340100001

Rubio-Arias, J. A., Marin-Cascales, E., Ramos-Campo, D. J., Hernandez, A. V., & Perez-Lopez, F. R. (2017). Effect of exercise on sleep quality and insomnia in middle-aged women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Maturitas, 100, 49-56.

Sivertsen, B., Lallukka, T., Petrie, K. J., Steingrimsdottir, O. A., Stubhaug, A., & Nielsen, C. S. (2015). Sleep and pain sensitivity in adults. Pain, 156(8), 1433-1439.

Speck, V., Schlereth, T., Birklein, F., & Maihofner, C. (2017). Increased prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in CRPS. European Journal of Pain, 21(3), 466-473.

van de Vusse, A. C., Stomp-van den Berg, S. G. M., Kessels, A. H. F., & Weber, W. E. J. (2004). Randomised controlled trial of gabapentin in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type 1 ISRCTN84121379. Bmc Neurology, 4.

Vlaeyen, J. W., Crombez, G., & Linton, S. J. (2016). The fear-avoidance model of pain. Pain, 157(8), 1588-1589.

Zhu, G. C., Bottger, K., Slater, H., Cook, C., Farrell, S. F., Hailey, L., . . . Schmid, A. B. (2019). Concurrent validity of a low-cost and time-efficient clinical sensory test battery to evaluate somatosensory dysfunction. European Journal of Pain, 23(10), 1826-1838.

![Image 2. Budapest Criteria for CRPS Diagnosis [6], with patient’s signs and symptoms highlighted.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52994853e4b0a6ba0e3606bc/1613789971449-86QAJ5FVKY1K3KME5UX3/Budapest+Criteria.png)