Thoracic Outlet Syndrome - clinical assessment

Recently I listed to a fantastic podcast by Jo Gibson through Clinical Edge on Thoracic Outlet Syndrome and was thrilled to learn some advances which have taken place in our knowledge of this condition since I first published a blog on the topic in 2013. Seven years later and I am excited to share a revised piece that includes the latest ideas around clinical assessment, and in particular sensory testing in the differential diagnosis of this challenging condition.

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a syndrome/condition that encompasses a cluster of upper extremity symptoms which are due to compression of the neurovascular bundle by various structures in the area just above the first rib and behind the clavicle. The three most common regions where compressions is thought to occur is the intrascalene triangle, the costoclavicular triangle and the subcoracoid space.

Thoracic outlet syndrome was first described in 1927 by Adson and colleagues and known at this time as scalenus anticus syndrome. The formal term that most authors refers to as Thoracic outlet syndrome was derived by Peet and colleagues in 1956.

CLASSIFICATION OF THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME

In the current research trials, thoracic outlet syndrome is being classified into the following categories:

The first category is Vascular TOS, which includes arterial and venous and accounts for ~ 5% of all presentations.

The second category is Neurological TOS, which is broken down further into true and symptomatic TOS.

Symptomatic TOS comprises over 80% of all people presenting with this diagnosis. That is to say there is a huge proportion of patients will present with no radiological or electrophysical abnormality (Hooper et al., 2010a; Sanders et al., 2007; Kaczynski et al., 2013).

Thoracic outlet syndrome remains a diagnosis of exclusion and recent studies have revealed that it can take up to 60 months (5 years) for patients with symptomatic TOS to gain an appropriate diagnosis. This statistic shocked me. It is known that TOS is a cluster of neurological, pain and vascular deficits that sit on a continuum from intermittent to permanent impairments. It is also know that presentation of these symptoms vary from patient to patient. Often it is difficult to say specifically where the point of compression is and radiological and electrophysical testing can present as normal. So what exactly can we look for in our clinical assessment to assist with diagnosis?

DIAGNOSIS & CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome remains disputed as there is no standard objective test to confirm clinical impressions. It remains a diagnosis of exclusion (Hooper, et al., 2010, p. 76).

“Diagnosis of symptomatic thoracic outlet syndrome is dependent on a systematic, comprehensive upper-body examination” (Watson et al, 2009, p.588).

Watson and colleagues provide a two-part masterclass which comprehensively outlines the musculoskeletal examination required to arrive at the diagnosis of TOS, and provide treatment strategies to manage scapular dyskinesia, muscular imbalances and improve container dysfunction. It was one of the best sources I came across in this body of research and applicable to every day clinical practice. For further reading on clinical presentation, diagnosis and management I would refer you to these two articles.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2009). Thoracic outlet syndrome part 1: Clinical manifestations, differentiation and treatment pathways. Manual therapy, 14(6), 586-595.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome Part 2: Conservative management of thoracic outlet. Manual therapy, 15(4), 305-314.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In 2016, Illig et al published an article discussing the reporting standards of vascular surgeons for the diagnosis of neurogenic TOS. These standards state that 3 of the 4 following should be present.

Signs and symptoms of pathology at the thoracic outlet (scalene triangle or pectoral insertion)

Signs and symptoms of nerve compression which worsens with overhead movement

Absence of other pathology

Positive response to scalene muscle test injection

Interestingly, these same authors state that EMG is not required and Brachial plexus imaging is not required to make an accurate diagnosis of nTOS (Illig et al., 2016, p.e30).

In my first blog, there is further detail on the comprehensive upper-body examination, clinical presentation and differential diagnosis. What I have learnt through the podcast is that we can add to this examination a useful questionnaire and newly developed clinical quantitative sensory testing for small nerve fibre conduction.

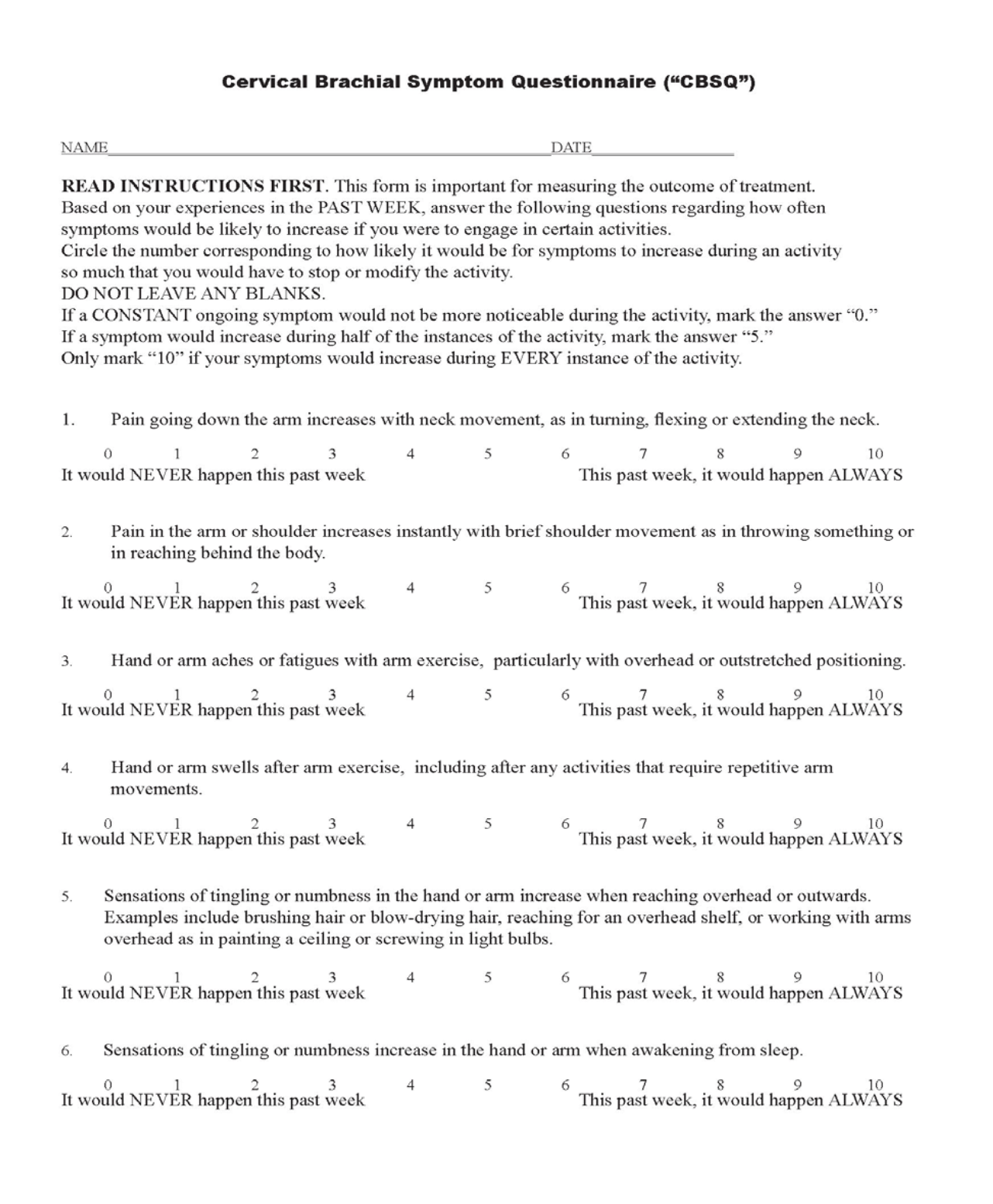

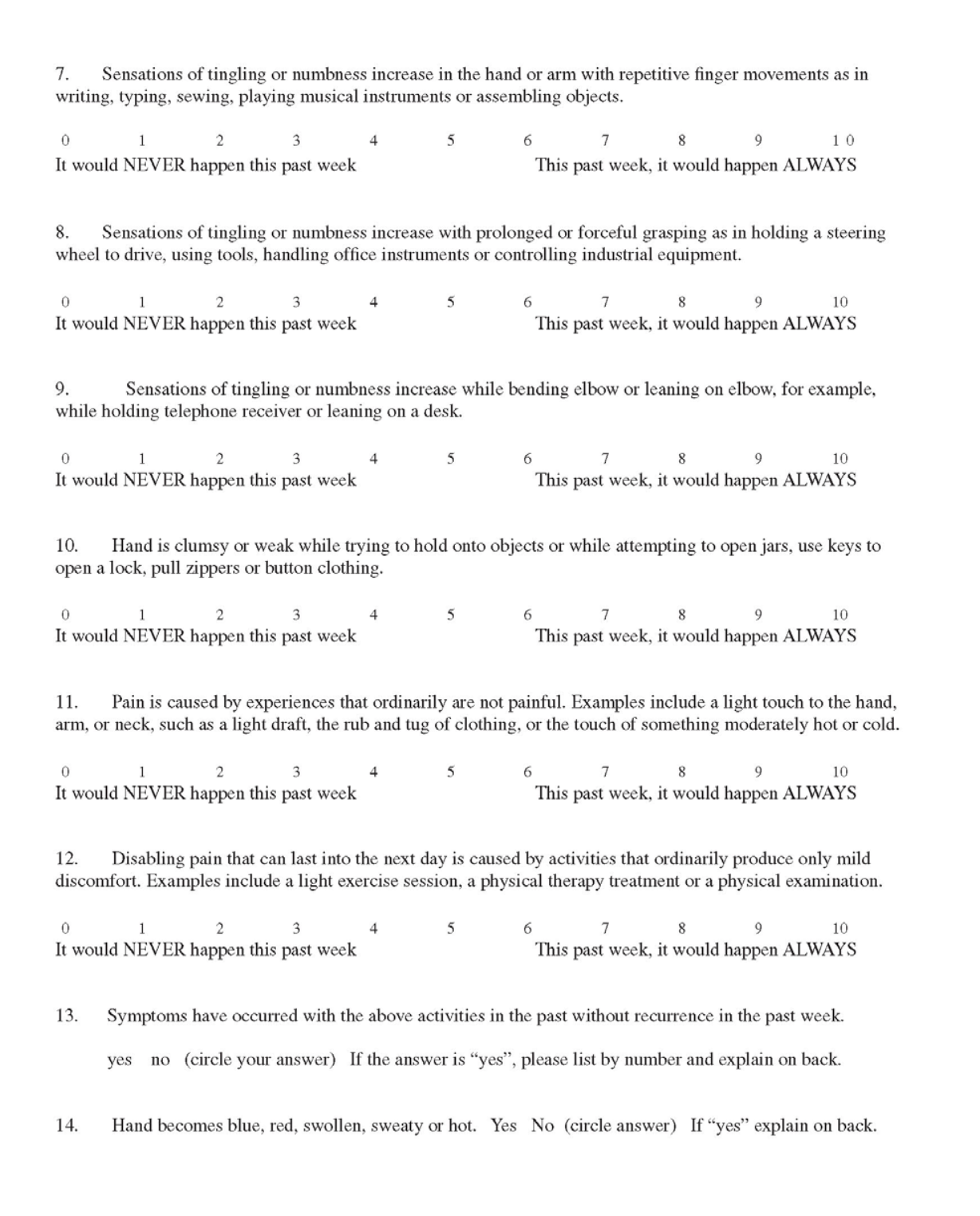

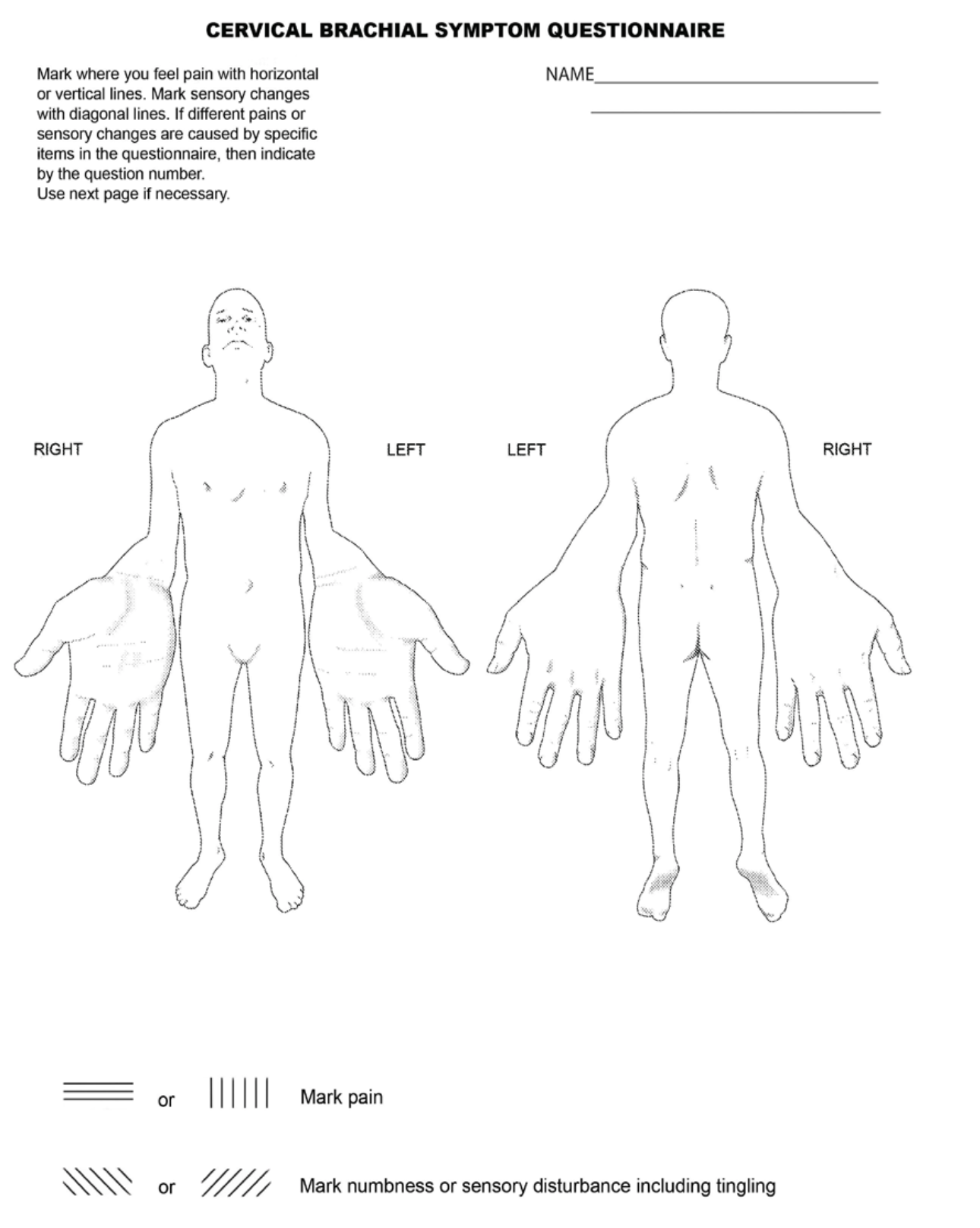

CERVICOBRACHIAL SYMPTOM QUESTIONNAIRE (CBSQ)

It is hypothesized that patients with TOS should not demonstrate an overabundance of symptoms throughout the arm, neck and shoulder region characterized as widespread pain. Instead, they should demonstrate patterns of sensory disturbance and motor weakness localized to the lower trunk of the brachial plexus. The CSBQ was developed to help differentiate patients with localized versus widespread pain to assist with differential diagnosis. Content validity of the questions within this questionnaire was determined collectively by two vascular surgeons and three neurosurgeons. This questionnaire was developed and validated in 2007 by Jordan, Ahn and Gelabert.

SMALL FIBRE SENSORY TESTING

Previously I thought of neurological testing as part of the “ruling out” process when trying to identify patients with cervical radiculopathy and other conditions. After listening to the podcast and reading this paper by Ridehalgh et al (2018), I can now see that it is important to examine both the large diameter and small diameter nerve fibres.

Ridehalgh, Sandy-Hindmarch & Schmid (2018) developed a testing procedure which involves combining warm/cold and mechanical pain threshold assessment to identify small fibre degeneration (SFD). Their results showed that:

Normal warm (WDT) or cold (CDT) sensation is highly sensitive (0.98) to rule out SFD, but has low specificity.

Reduction in pinprick is high specific (0.88) to rule in SFD.

Warm/cold detection

First the examiner used a coin at room temperature (cold testing) and assessed the lateral upper arm and palmar side of the index finger asking the patient to rate the temperature as same, colder or warmer. If the answer was “warmer at the finger” this would indicate a deficit in cold detection.

The the examiner would repeat the procedure with a coin that had been in their pocket for 30 minutes (warm testing).

No change in rating of cold/warm testing was interpreted as an indication that no small fibre degeneration was present.

Mechanical pain threshold

The examiner could use either a neurotip or toothpick.

The median nerve was tested by comparing detection of a “sharp” sensation at the ventral forearm and palmar tip of the index finger. Again the patient was asked to rate the sensation as same, sharper, less sharp.

The radial nerve was tested using the lateral upper arm and the palmar aspect of the index finger.

As you can see, both of these simple bedside tests for small fibre conduction can be easy to incorporate in your overall examination of a patient with potential TOS. I am eager to also try the CBSQ with suspected patients to assist with my overall clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis. I want to thank Jo Gibson and David Pope for sharing such valuable information on their blog and helping to guide me in the right direction with my assessment and management of these patients in the future.

Sian

References:

Hooper, T. L., Denton, J., McGalliard, M. K., Brismée, J.-M., & Sizer Jr, P. S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 18(2), 74.

Hooper, T. L., Denton, J., McGalliard, M. K., Brismee, J. M., & Sizer, P. S., Jr. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 18(3), 132-138.

Illig, K. A., Donahue, D., Duncan, A., Freischlag, J., Gelabert, H., Johansen, K., ... & Thompson, R. (2016). Reporting standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of vascular surgery, 64(3), e23-e35.

Kaczynski, J., & Fligelstone, L. (2013). Surgical and Functional Outcomes After Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Decompression via Supraclavicular Approach: A 10-Year Single Centre Experience. Journal of Current Surgery, 3(1), 7-12.

Peet, R. M., Henriksen, J. D., Anderson, T., & Martin, G. M. (1956). Thoracic-outlet syndrome: evaluation of a therapeutic exercise program. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the staff meetings. Mayo Clinic.

Ridehalgh, C., Sandy-Hindmarch, O. P., & Schmid, A. B. (2018). Validity of clinical small–fiber sensory testing to detect small–nerve fiber degeneration. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 48(10), 767-774.

Sanders, R. J. (2013). Anatomy of the Thoracic Outlet and Related Structures Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (pp. 17-24): Springer.

Sanders, R. J., Hammond, S. L., & Rao, N. M. (2007). Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of vascular surgery, 46(3), 601-604.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2009). Thoracic outlet syndrome part 1: Clinical manifestations, differentiation and treatment pathways. Manual therapy, 14(6), 586-595.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome Part 2: Conservative management of thoracic outlet. Manual therapy, 15(4), 305-314.