Functional facts about hip muscles

This blog is a compilation of fun and functional facts about the muscles which control and move the hip. Presented here are concepts around anatomy, muscle synergies and changes to muscle function which occur with pathology, specifically OA. There is also a review of the current knowledge and details that drive our decision making around exercise prescription for retraining hip strength, particularly hip extension, abduction and external rotation strength.

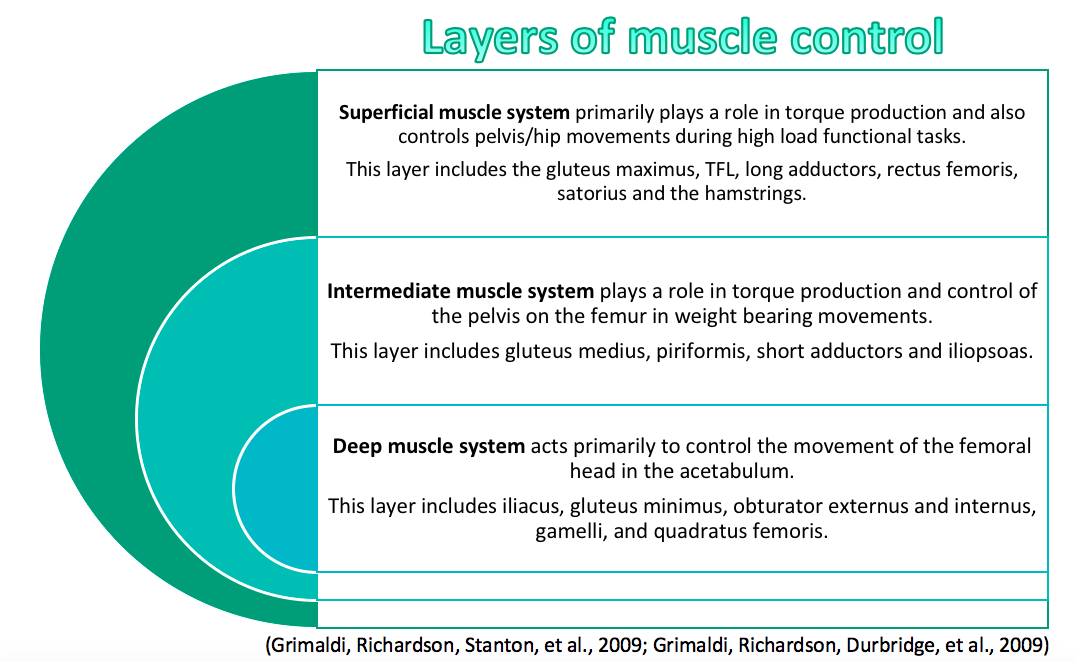

A review of the anatomy

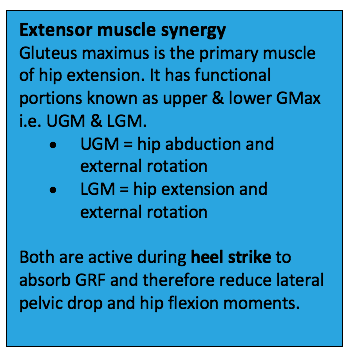

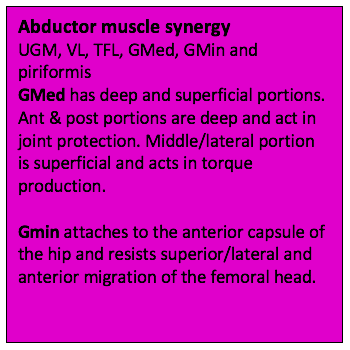

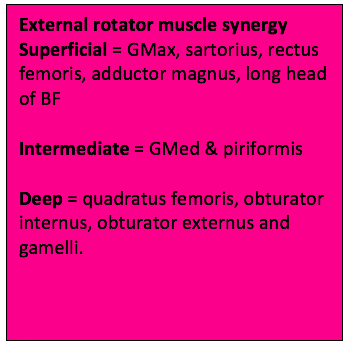

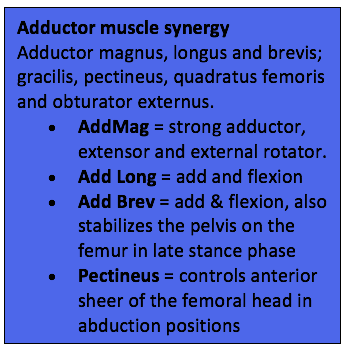

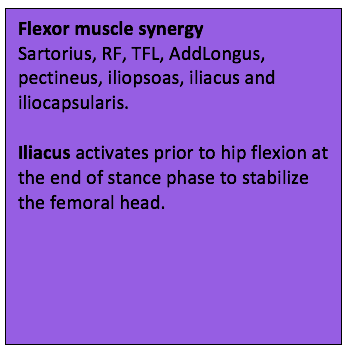

Muscles work in synergy groups

Not only about the glutes!

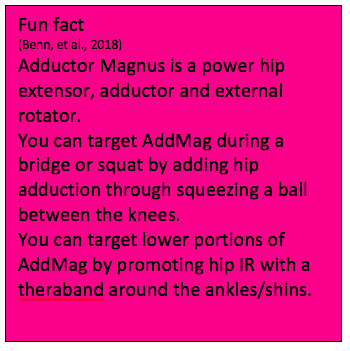

An article was recently published by Benn, et al (2018) talking about the functional anatomy of adductor magnus. This article highlights that hip extension is not all about GMax and BF and that AddM might play an important role in stabilisation and counter forces at the hip. They describe two functionally specific portions.

- The upper portion is involved in hip extension and adduction and some ER.

- The lower portion is involved in hip extension, adduction and internal rotation.

- Both loose adduction force production as hip flexion increases.

Many studies looking at hip extension muscle moments only talk about gluteus maximus and bicep femoris. Hardly ever is adductor magnus a clinical consideration.

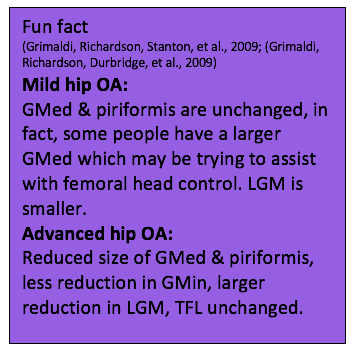

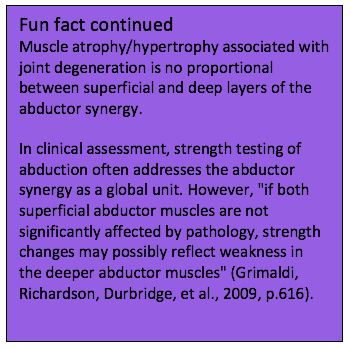

Changes in muscle size with pathology

There are 2 Grimaldi articles talking about muscle changes in hip OA and provoking us to think about functional units within the muscles. These articles tell us about which muscles are likely to be affected by hip OA and where we can target our treatments.

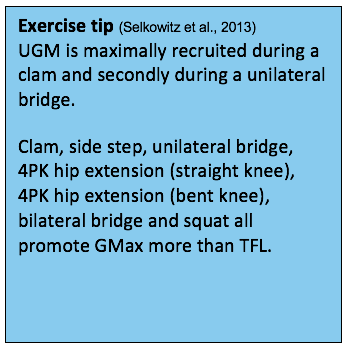

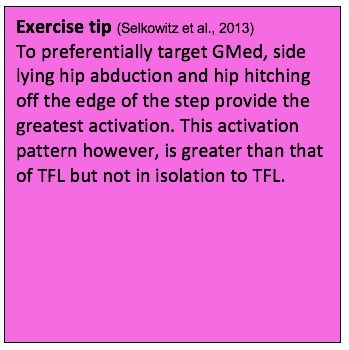

Choosing exercise positions based on muscle bias

Bridges are used to strengthen hip extension and are important for bed mobility and preceed functional tasks such as sit-to-stand and kneeling. Kang, Choung & Jeon (2016) found that as hip abduction angle increases from 0 to 15 to 30 degree, there is an increase in GMax activation and reduction in anterior pelvic tilting and erector spinae muscle activity. Bridge with increasing hip abduction increases GM and decreases BF and ES (kang, Choung & Jeon., 2016).

Prone hip extension (PHE) is often used to assess hip extension strength and provided as a rehabilitation exercise.

- Jeon and colleagues (2016) found that when PHE is performed off the edge of a table with the moving leg held at 90 degrees knee flexion, GMax activation is promoted over biceps femoris.

- Kang et al (2013) found that as hip abduction angle increases in PHE (0 to 15 to 30 degrees) increases, there is an increase in GMax activation over biceps femoris. Therefore, if you want to increase hamstring muscle strength in this exercise, 0 degrees abduction is recommended, whereas if you want to increase GM activity, then 30 degrees abduction is recommended.

- Chance-Larsen, Littlewood & Garth (2010) found that knee angle during the PHE changes muscle activation i.e. with the knee extended the hamstrings are far more likely to activate before and more than GMax.

Clams are used to target GMax and strengthen hip external rotation. Koh, Park & Jung (2016) found that providing visual feedback in the form of watching the ASIS of the topside hip allows for patients to perform the clam movement without pelvic rotation, which increases gluteal activation and accuracy of performance.

Hopefully this blog has provoked you to think a little more about the tests we used for hip strength (bridges, side lying abduction, clams) and which muscles they are truely targeting. When teaching these movements, remember to ask your patient where they feel the muscle contraction to ensure they are feeling the correct location.

Sian :)

Other blogs which might interest you

- Which exercises target gluteal muscles while minimizing the activation of TFL?

- Muscle synergies of the hip and pelvis

- Assessing hip strength

- Motor control impairments associated with hip OA

References

Benn, M. L., Pizzari, T., Rath, L., Tucker, K., & Semciw, A. I. (2018). Adductor magnus: An EMG investigation into proximal and distal portions and direction specific action. Clinical Anatomy.

Chance-Larsen, K., Littlewood, C., & Garth, A. (2010). Prone hip extension with lower abdominal hollowing improves the relative timing of gluteus maximus activation in relation to biceps femoris. Manual Therapy, 15(1), 61-65.

Crossley, K. M., Zhang, W.-J., Schache, A. G., Bryant, A., & Cowan, S. M. (2011). Performance on the single-leg squat task indicates hip abductor muscle function. The American journal of sports medicine, 39(4), 866-873.

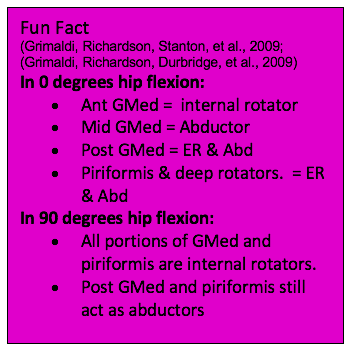

Grimaldi, A., Richardson, C., Stanton, W., Durbridge, G., Donnelly, W., & Hides, J. (2009). The association between degenerative hip joint pathology and size of the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and piriformis muscles. Manual therapy, 14(6), 605-610.

Grimaldi, A., Richardson, C., Durbridge, G., Donnelly, W., Darnell, R., & Hides, J. (2009). The association between degenerative hip joint pathology and size of the gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata muscles. Manual therapy, 14(6), 611-617.

Grimaldi, A. (2011). Assessing lateral stability of the hip and pelvis. Manual Therapy, 16(1), 26-32.

Jeon, I. C., Hwang, U. J., Jung, S. H., & Kwon, O. Y. (2016). Comparison of gluteus maximus and hamstring electromyographic activity and lumbopelvic motion during three different prone hip extension exercises in healthy volunteers. Physical Therapy in Sport, 22, 35-40.

Kang, S. Y., Jeon, H. S., Kwon, O., Cynn, H. S., & Choi, B. (2013). Activation of the gluteus maximus and hamstring muscles during prone hip extension with knee flexion in three hip abduction positions. Manual therapy, 18(4), 303-307.

Kang, S. Y., Choung, S. D., & Jeon, H. S. (2016). Modifying the hip abduction angle during bridging exercise can facilitate gluteus maximus activity. Manual therapy, 22, 211-215.

Koh, E. K., Park, K. N., & Jung, D. Y. (2016). Effect of feedback techniques for lower back pain on gluteus maximus and oblique abdominal muscle activity and angle of pelvic rotation during the clam exercise. Physical Therapy in Sport, 22, 6-10.

Retchford, T. H., Crossley, K. M., Grimaldi, A., Kemp, J. L., & Cowan, S. M. (2013). Can local muscles augment stability in the hip? A narrative literature review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact, 13(1), 1-12.

Selkowitz, D. M., Beneck, G. J., & Powers, C. M. (2013). Which Exercises Target the Gluteal Muscles While Minimizing Activation of the Tensor Fascia Lata? Electromyographic Assessment Using Fine-Wire Electrodes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 43(2), 54-64.