Breathing pattern disorders - where do they fit in?

The previous blog introduced why I feel breathing patterns are something we should be spending more time assessing or at least delving into more detail about. This blog looks at the different aspects of assessment - questioning and physical tests - that we can build into clinical practice.

The first question to address is - where does it fit in?

Do we start regionally or holistically? For example, a patient presents with chronic lower back pain and structural diagnostic label of a disc bulge.

- Day 1 - are you going to look at lumbar active range of movement, palpation, muscle strength and length tests. Then day 2 - look at the area above and below, clear a neurological exam, check a neurodynamic exam. Then day 3 - spend more time looking at breathing, motor control and functional positioning.

Or....

- Day 1 - are you going to look more holistically at the resting posture, quiet breathing and gait. Then build out the assessment to a more focussed structural or body-region-specific assessment?

How we choose and order the priority of our clinical assessment is a clinical reasoning challenging that we are faced with daily. What I am finding more frequently is that my approach changes depending on the person and depending on the program. I have to ask myself - is it more important to reproduce their pain on the first session or is it more important to look at global contributing influences to their pain - like abnormal breathing?

I don't think there is a right or wrong, and as I continue to practice, my ability to choose seems to become more refined. I do think that is all comes down to the personality of the individual and the expectations for treatment and recovery. Fundamentally breathing is like all our other areas of assessment and treatment. There is so much complexity to breathing alone, that it is impossible to assess every aspect in detail. But, after reading this book, these are the few key areas and tactics for treatment that I'll try to use in 2018.

"How we breathe and how we feel are intimately conjoined in a two-way loop." (Chaitow, Bradley & Gilbert., 2014, p. 24).

Patients don’t just choose to breath abnormally - their bodies are forcing them to adapt to a problem and our role as therapists is to understand the underlying drivers. When reading this book I came across the section below, which suddenly helped me grasp the reason breathing abnormally can have such a profound impact on the human body.

“Both respiratory suspension and over-breathing in preparation for action are unbalanced, in the sense that the individual is not living entirely in the present. This projection into the future creates a discrepancy between actual and anticipated metabolic needs. The trouble arises when the threat is non-physical or not imminent. If such feelings become habitual, then the preparation will become chronic.” (Gilbert., 2014, p.82).

Assessment of breathing patterns

The assessment by a physiotherapist is more than just physical, it includes understanding the past medical history, social history, medication history and general health for conditions or contributing factors to breathing disorders. Only once these have been questioned for and excluded, should one continue to look at physical and structural tests.

Breathing assessment might comment on posture and patterning:

- If the breathing is diaphragmatic, abdominal etc. Where is the movement coming from?

- Place one hand on the chest and other on the stomach. Inhale and comment on the movement of the hands. If the upper hands moves first and more then this is called upper chest breathing (Chaitow., 2014, p. 101).

- How much of the abdomen moves and in which direction? Does it expand forward, sideways or suck inwards?

- How much to the accessory muscles activation can be seen?

- Do the shoulders elevation during breathing? What is the resting position of the clavicles and scapula?

- What is the rate of breathing?

- How would you rate the duration of inspiration compared to expiration i.e. does the person completely exhale or stay hyper-inflated?

- Is there movement felt in-between the shoulder blades (posterior mediastinum) during inspiration or is all of the movement anterior in the chest?

- Is there a natural pause at the end of expiration?

- Does the person exhibit any altered phonation (voice changes) while they breathe?

Assessment can be performed in supine, sitting, quadruped or standing - it depends on how demanding you wish to make the postural component of breathing. For example, if you assess a patient in supine there is not a lot of room to palpation lateral and posterior expansion of the ribs. If you assess them on hands and knees (quadruped), you get a sense for scapulohumeral positioning, neck strength and expansion of the full thoracic spine, but is is more difficult to visualise the clavicles and accessory muscles.

Assessment in sitting

When assessing a person in sitting I like to focus on movement of the sternum. Often patients don't realise it, but they are hitching their shoulders up, activating neck muscles and lifting the sternum upwards (cranially). The ideal breathing pattern would not exhibit scapula elevation, accessory muscle activation and instead show anterior movement of the sternum and posterior expansion of the ribs. To assess this, the patient can place one hand on their chest and belly while you place one hand between the shoulder blades and one on the top of one shoulder. This also provides the patient with a lot of proprioceptive feedback when moving towards changing their pattern.

Assessment in supine

What I look for in supine is different from sitting and focusses on abdominal movement and rib flare. When in lying, if you can palpate the border of the inferior ribs the patient is demonstrating rib flare, which often indicates a loss of synchronisation of the abdominal muscles with the diaphragm and over-activity of the spinal extensor muscles. As the patient breathes in there should be an equal distribution of movement throughout the chest, not just the stomach lifting forward. As the patient breathes out, the ribs shoulder downwardly rotate and connect into the abdominal wall. This is why noting inhalation:exhalation ratios are important because if the patient doesn't fully exhale, their ribs will never drop down into the abdomen.

Assessment in quadruped

The key finding I look for in quadruped is how well a person can position their scapula on the thorax. More importantly, as they exhale, if the ribs drop down towards the table the scapula will wing off the thorax (seen in image 2). If this occurs the patient is not able to stabilise their upper body while in a static position and this exercise will be a great starting point for rehabilitation.

Other positions for assessment

The author of the book mentioned above describes in detail what an assessment entails with a patient sitting but also suggests that side lying hip abduction SLR and prone active SLR are great tests for palpating where movement begins and providing information about hip abduction or extension being initiated in the lumbar spine. These lumbar muscles are also breathing muscles, therefore if altered timing is found during the assessment, it may suggest poor synchronisation between muscle regions.

You should also spend time watching how the patients spine is moving and the distribution of flexion (which I refer to often as segmental control). This often tells you how well ribs are moving and air is being distributed throughout the chest. You can observe their spinal movements in flexion or just as they lie prone. This is not diagnostic but a helpful way to approach your observation technique.

I actually have been integrating more observatory techniques into my practice to compliment my structural tests.

So the observation of breathing can be built into many other tests we commonly use - it just has to be a specific intension and focus of what you are looking for.

Some other tests we can include:

- Measuring respiratory rate

- Measuring controlled expiratory pause.

- “While no standardized test yet exist, breath-hold times are recorded by many clinicians as part of HVS/BPD assessment. Failure to hold beyond 30 seconds is considered by some a positive diagnostic sign of chronic hyperventilation (Gardner 1996).” (bradley., 2014, p. 122).

- Pulse-oximetry

- Peak-expiratory Flow Rate

- Range of movement and palpation assessment of the thoracic spine, shoulder girdle and ribs

- Looking a voice control during breathing. Things to observe include (Au Zveglic., 2014, p.208):

- The audibility if inspiration

- The speed of speech

- The ability to finish phrases and sentences

- The quality of the voice

Questionnaires:

“Breathing is a dynamic system which is under the influence of many factors. These are of physical and pathological nature, as well as from psychic and emotional origin and also may be part of social and behavioural patterns.” (Courtney & van Dixhoorn., 2014, p.137). Therefore, not all aspects of breathing can be assessed objectively. I love using questionnaires to improve my understanding of asking questions. I am not the most consistent in applying them to my patients - and perhaps this is an area I can improve on - but I integrate the questions into the subjective assessment.

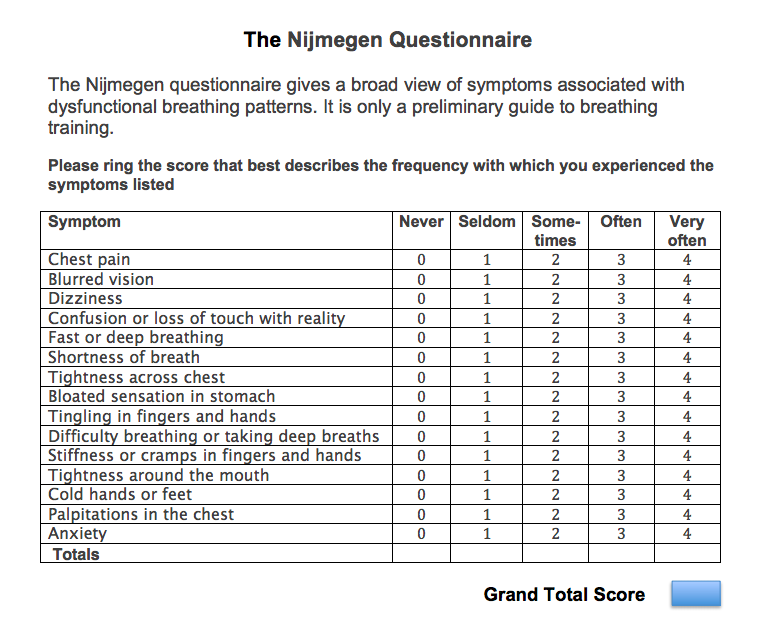

Nijmegen Questionnaire:

- The Nijmegen Questionnaire (NQ) assesses stress and arousal, presumed consequences and symptoms of hypocapnia and difficulty breathing.

- The normative values differ depending on the country/population evaluated but it is generally accepted that a score >19 (out of max 64) demonstrates the presence of respiratory distress and dysfunction.

- This questionnaire is used in populations other than breathing disorders (heart and lung disease, anxiety, depression) but is the most commonly mentioned one I’ve read about in the assessment of breathing pattern disorders.

“As yet there is no ‘gold standard’ laboratory test to clinch the diagnosis of chronic HVS. However, the Nijmegen Questionnaire is the next best thing, and provides a non-invasive test of high sensitivity (up to 91%) and specificity up to 95% (Van Dixhoorn & Duivenvoorden 1985)" (Bradley., 2014, p.121).

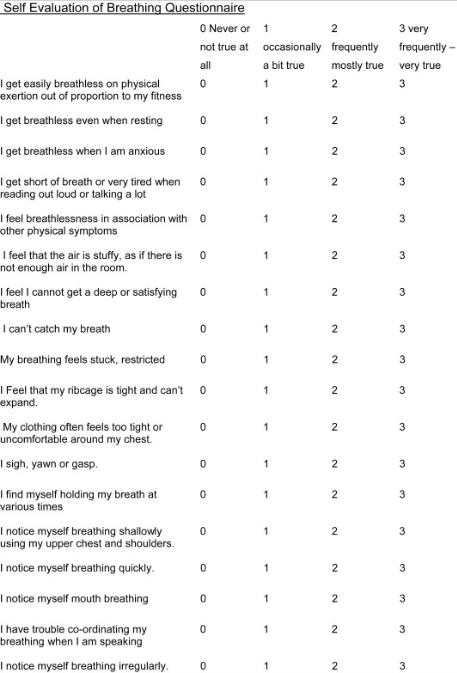

The Self-Efficacy Breathing Questionnaire:

- “The SEBQ is useful as a means of evaluating the quality and quantity of uncomfortable respiratory sensations, and the person’s perception of their own breathing, and may help to give insight into the origins of the discomfort.” (Courtney & van Dixhoorn., 2014, p.140)

- It has questions relating to air hunger and ones relating to effort of breathing.

Image source: https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S1360859210000951-gr2.jpg

Breathing difficulties come in many symptoms and forms and there is no single measure or diagnostic tool. Clinicians need to be aware of the variety of symptoms associated with breathing pattern disorders to best identity, document and address them.

We're over half way through the book now and I hope your thinking around breathing is starting to expand (as well as the frequency of nasal breaths while you read). The next blog looks at tips for treatment drawn from physiotherapy, osteopathic and more alternative approaches.

Sian

References:

Chaitow, L., Gilbert, C., & Morrison, D. (2014). Recognizing and Treating Breathing Disorders E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.