Ankle Syndesmosis Injuries - Assessment

Ankle syndesmosis injuries are becoming increasingly more common. Possibly, our assessment is more thorough and imaging is more detailed, giving a greater number of confirmed syndesmosis injuries. Possibly, we are now better at preventing ankle inversion sprains and lateral ligament injuries, with prophylactic taping and proprioceptive prevention programs reducing the number of lateral ligament sprains, resulting in a higher proportion of ankle injuries being syndesmosis ligament damage. Either way, we need to ensure we are as effective at managing syndesmosis injuries as lateral ankle sprains.

To brush up on your anatomy, read the previous blog regarding the syndesmosis, then continue with assessment of this area.

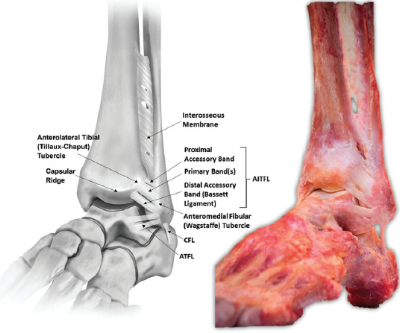

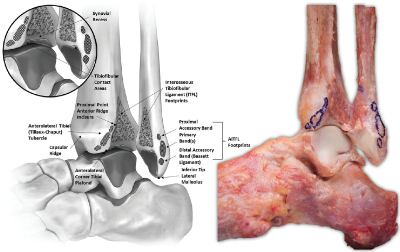

Ankle syndesmosis ligaments

Subjective

The subjective assessment is crucial in diagnosing a syndesmosis injury. Targeted questioning regarding mechanism of injury (MOI), location of pain, ability to weight bear and the type of sport the individual was participating in, provides valuable information indicating a syndesmosis injury.

In particular, questioning should include:

Mechanism of Injury (MOI)

Usually forced external rotation and dorsiflexion of foot and ankle:

Athlete rapidly internally rotates in pivot on an externally rotated foot (similar to ACL injury MOI), or

Another player forces the foot into external rotation while the foot is planted, or

Direct contact to the lateral heel forces the foot/ankle into external rotation while the player is on the ground (Nussbaum et al, 2001).

Hyperdorsiflexion, where the talus is forced upward into the ankle mortice, is less common.

Brosky (1995) claimed that once the ankle achieves maximal external rotation, adding either dorsiflexion or plantarflexion will cause an injury, so an external rotation with plantarflexion can also cause syndesmosis injury.

Location of Injury

Most report pain and point tenderness over the AITFL and/or PITFL.

Tenderness can extend superiorly into interossesous membrane.

There is a strong correlation between the distance of tenderness up the tibia and the length of time taken to return to sport (Nussbaum et al, 2001).

Type of Sport

While injuries can occur in any sport where external rotation occurs, it is most common in field sports and skiing.

Skiing - common as skiers complete rapid external rotation on sharp turns, usually the skier catches the inside edge of their ski causing forced foot external rotation.

Football - occurs commonly with forced internal rotation of the lower leg or knee while the foot is planted (similar MOI to MCL injury).

Ability to Weightbear (WB)

This does depend on the severity of injury. But many athletes who sustain more than a grade 1 injury will not be able to continue play due to an inability to weight bear without support of crutches.

Patients experience pain & instability on push off or when pivoting on a planted foot. Asking a patient about their confidence to hop on one leg is a great question to explore their confidence levels around loading the ankle and will often allude to a feeling on instability.

Time Since Injury

Injuries can be classified into acute (less than 3 weeks), subacute (3 weeks to 3 months) and chronic (greater than 3 months).

Most ankle injuries appear similar in the first 3 weeks, so clarifying the MOI is crucial in diagnosis.

Corresponding Swelling

Amount of swelling is variable, isolated sprains to tibiofibular ligaments often have a small pocket of fluid over the syndesmosis ligaments, as the ligaments are intra-articular.

Sprains to medial or lateral ankle ligaments tend to have much greater swelling.

With syndemosis injuries, swelling often occurs 24 hours after injury, rather than immediately with lateral ligament sprains.

Medical Screening

This often forgotten section can affect prognosis.

Conditions such as diabetes, vascular disease, neuropathy, alcohol use etc can prolong recovery.

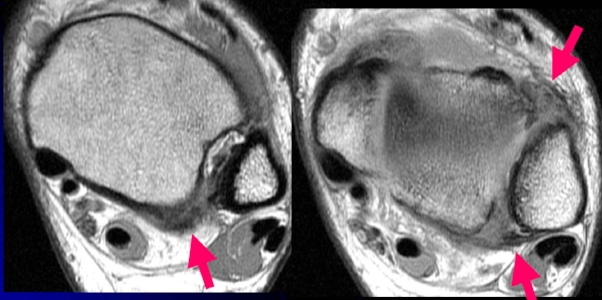

MRI of ankle syndesmosis injury. Arrows show AITFL and PITFL injury damage

Classification

Two systems are commonly used to diagnose high ankle sprains. The graded ankle measurement and the Danis-Weber classification of ankle fractures are both used to diagnose ankle injuries.

The graded system classifies instability based on mechanism of injury, the degree of ankle instability and extent of ligament disruption.

Grade 1

Consists of a partial tear of AITFL, anterior deltoid & distal interosseous ligament (IOL),

There is no diastasis (widening of the joint space) so the joint is considered stable.

Grade 2

The rotational force tears anterior and deep deltoid ligaments, AITFL, with partial tears to IOL.

Very difficult to diagnose on x-ray, can only be diagnosed on weightbearing imaging.

Grade 2 injuries are often classified as latently unstable.

Underestimating the severity of this injury can often lead to further injury such as interosseous ossification, chronic pain & stiffness.

A chronic injury occurs when no treatment is given until at least 3 months after injury, there is greater risk of osteoarthritis, higher rates of ossification & poorer functional outcomes.

Grade 3

Complete disruption of syndesmosis + gross instability.

Visible on plain unweighted x-ray, a diastasis (joint widening) will be evident at rest and greater on weightbearing.

Danis-Weber Classification

Forceful external rotation can cause a concomitant fibula fracture. Where ligament damage is classified using the grading scale, fractures are classified using the Danis-Weber system.

Weber B - the fracture occurs at the level of the distal syndesmosis, with no disruption of the interosseous membrane.

Weber C - there is disruption of the deltoid ligament (caused by external rotation), with a fracture above the level of the distal syndesmosis, 70% of syndesmosis injuries with fractures are Weber C injuries.

Maisonneuve - a proximal fibula fracture, the more proximal the fracture, the greater the risk of syndesmosis disruption with instability (Porter 2014).

Weber C fracture with syndesmosis disruption, A=anterior/posterior view, B=mortise view, C=lateral view

Clinical Exam

When you suspect a syndesmosis injury, based on your subjective assessment, a thorough physical examination should be performed. The following tests can indicate a syndesmosis injury.

Observation

Swelling above the tibiofibular joint line occurring within 24 hours could indicate syndesmosis injury.

Swelling occurring soon after injury which is more localised to the lateral ankle or global swelling around entire foot/ankle is more likely lateral ligaments.

Gait

A patient with a syndesmosis injury often walks with a heel-raised pattern to limit the amount of dorsiflexion and reduce push-off mechanism.

The patient will have reduced power at push-off, often limited by pain.

A patient with a lateral ligament injury will often weightbear through the heel to avoid plantarflexion/inversion (the mechanism of lateral ankle sprain).

The below video shows walking through the heel (consistent with a lateral ligament injury), followed by a heel-raised pattern (consistent with a syndesmosis injury).

Functional Exam

A patient's presentation will appear similar to a lateral ankle sprain, however their biggest restriction will be dorsiflexion and weightbearing.

Squat - depth of squat restricted by anterior ankle pain.

Single Leg Stance - pain on increased weightbearing in ankle, pain appears deep inside ankle or along anterior or posterior joint line rather than lateral ankle.

Range of Motion

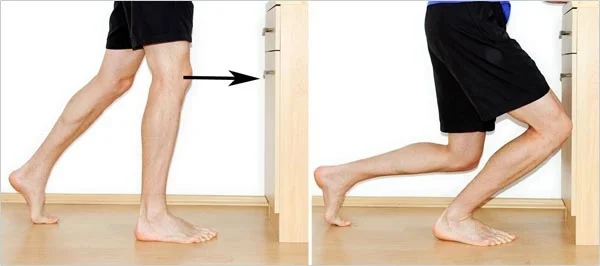

Dorsiflexion - knee to wall test (shown below) restricted by pain at anterior and posterior joint line, range should be almost equal to the contralateral side (e.g. L=10cm, R=11cm is adequate, L=8cm, R=13cm is clinically significant).

Plantarflexion - pain on pushing up onto toes, often pain onset at half range of plantarflexion.

Knee to Wall Test

Palpation

Palpate the entire length of the fibula.

You must exclude a Maisonneuve fracture in the mid-shaft of the fibula, exquisite tenderness along the bone could indicate a fracture.

Palpate the AITFL, PITFL and interosseous ligaments, as there is strong correlation between pain on palpation and ligamentous damage.

Special Tests

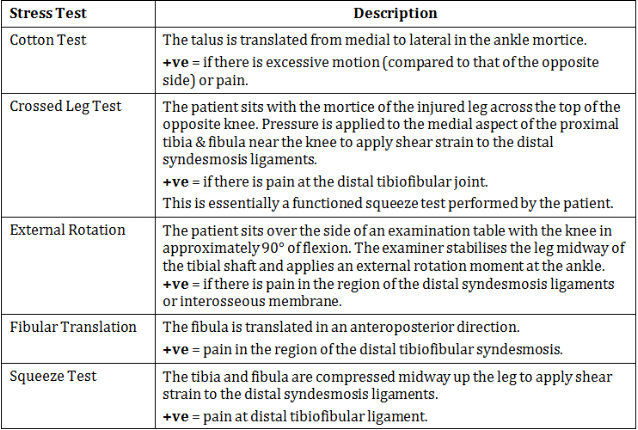

There are five tests which claim to specifically assess injury to syndesmosis ligaments, listed below.

Table from Williams and Allen (2010), page 462.

The external rotation test is the most reliable test, with low inter-tester error and high sensitivity. The squeeze test is also commonly used, however not as reliable as the external rotation test. Porter (2014) found the amount of external rotation range of motion at the foot and the amount of diastisis on x-ray were related to the degree of syndesmosis ligamentous damage. Nussbaum and colleagues (2001) found the distance of interossesous tenderness and a positive squeeze test correlated with the severity of the injury and the days lost from competition.

A thorough physical examination, focusing on palpation findings, range of motion, functional exam and special tests, in combination with a thorough subjective examination will indicate the possibility of a syndesmosis injury.

If your clinical findings indicate syndesmosis injury, you can refer for imaging to confirm diagnosis and determine correct management. A more severe syndemosis injury will require medical and/or surgical intervention. Imaging, along with clinical findings, will determine the severity of the syndesmosis injury, and indicate surgery.

Radiology

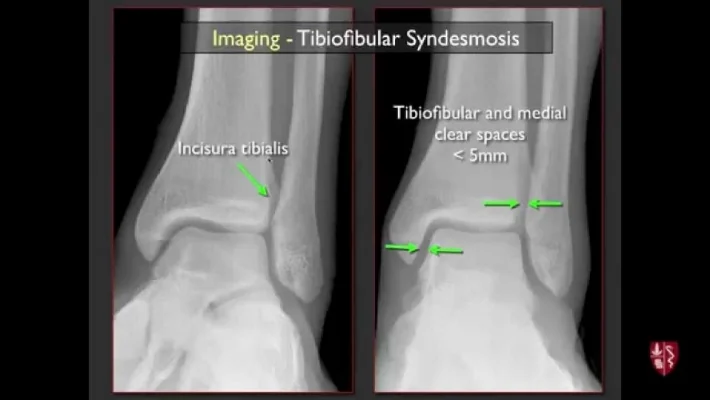

According to the Ottawa ankle rules, a patient who is unable to weightbear at the time of injury, or walk four steps in the clinic, should receive an x-ray to clear a fracture. If you are suspecting a syndesmosis injury, you should send for a weightbearing anterior/posterior (AP), lateral and mortice views.

Xenos (1995) showed lateral stress x-rays were more accurate than mortice views, however Lin (2006) found the mortice view gave the best assessment. Since the literature is uncertain, it is best to obtain all three views and assess carefully. Stress external rotation may be ordered if weightbearing views are inconclusive.

On x-ray, you are looking for the amount of medial clear space, widening of the tibiofibular clear space and tibiofibular overlap. An injury is present if there is greater than 1mm lateral subluxation or greater than 5mm separation between the tibia and fibula on mortice view. There are poor outcomes if there is a difference of greater than 1.5mm syndesmosis width (gap between tibia and fibula) compared to the unaffected side.

If plain x-rays are inconclusive, an MRI or CT should be performed. MRI scans are more effective in soft tissue injury, while CT is more effective when looking for bony injury (Porter 2014).

Now you have either confirmed or cleared a diagnosis of syndesmosis ligament injury, how do you treat it?

There will be a blog following, with the latest evidence for physiotherapy and surgical management for syndesmosis injuries!

Alicia

References:

Brosky, T., Nyland, J., Nitz, A., & Caborn, D. N. (1995). The ankle ligaments: consideration of syndesmotic injury and implications for rehabilitation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 21(4), 197-205.

Nussbaum, E. D., Hosea, T. M., Sieler, S. D., Incremona, B. R., & Kessler, D. E. (2001). Prospective evaluation of syndesmotic ankle sprains without diastasis. The American journal of sports medicine, 29(1), 31-35.

Porter, D. A., Jaggers, R. R., Barnes, A. F., & Rund, A. M. (2014). Optimal management of ankle syndesmosis injuries. Open access journal of sports medicine, 5, 173.

Williams, G. N., Jones, M. H., & Amendola, A. (2007). Syndesmotic ankle sprains in athletes. The American journal of sports medicine, 35(7), 1197-1207.

Xenos, J. S., Hopkinson, W. J., Mulligan, M. E., Olson, E. J., & Popovic, N. A. (1995). The tibiofibular syndesmosis. Evaluation of the ligamentous structures, methods of fixation, and radiographic assessment. JBJS, 77(6), 847-856.

Lin, C. F., Gross, M. T., & Weinhold, P. (2006). Ankle syndesmosis injuries: anatomy, biomechanics, mechanism of injury, and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and intervention. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 36(6), 372-384.