Finding your stride

Zion National Park

This year I have walked through some incredible National Parks including Zion, Kolob Canyon and Yosemite. Walking allows for a lot of time for reflection and something that came to mind a lot was how amazing it is that we can walk so effortlessly. I think the ease of walking is something we take for granted until our lives become so limited by not being able to walk anymore.

When I was going through Physiotherapy school I was taught a framework for conducting an assessment, which almost always began with - observation & gait. I was always taught that before we look at more finer details of assessment, we should begin with observation of functional movements and gait. On every assessment form I came across there was a space for it, but really what I thought we should write is "safe and independent" or "stair navigation with reciprocal gait". And generally brushed over it too quickly.

Image courtesy of Google Images

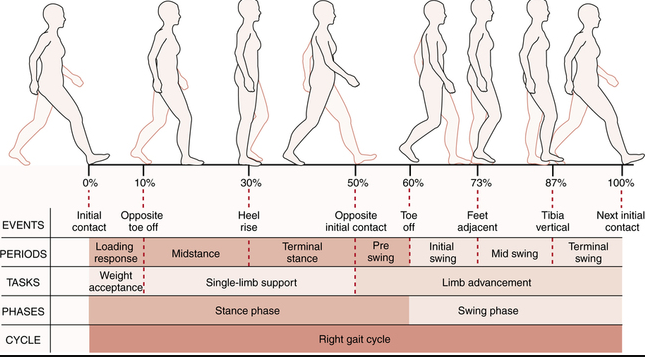

When thinking about gait analysis this picture comes to mind. I remember that during my final exams, and again last year when taking the NPTE, gait analysis was really just referring to the gait cycle. I've always considered gait to be important, but even more so now, I feel that gait is one of the most important parts of my assessment. Without being too corny, it is really important to build rehabilitation programs from the ground up and that means starting at the feet.

- Can you balance on one leg?

- Do you have the ankle mobility and calf strength required for progressing the tibia over the ankle?

- Do you have sufficient control in the quadriceps and gluteals to position the knee and hip in space?

- Is there safe and efficient transfer of energy and control of ground reaction forces?

How do you go about observing all of these elements during real-time gait for patients with ankle/foot/hip/back injuries? Luckily for me, every patient brings a phone to their treatment sessions and now I can film their gait pattern, slow it down and discuss the importance of gait on the rest of their body.

While the image above is important for understanding the fundamentals of gait, I don't think it helps us rehabilitate the movement. The remainder of this blog consists of my tips and cues for retraining walking.

Q1: How much noise do you make?

In the beginning I assess patient's both in their footwear and barefoot. Noise tells me that there is a lack of shock absorption through the heel on heel strike and this is never good.

Before I give them corrective exercises I simply ask "why does your foot make so much noise when you land on the floor?" The response normally is "I don't know?" and then I follow up with "can you walk more quietly?" Just drawing attention to something as simple as noise causes people to walk with more control in their hips and better control of eccentric plantarflexion as they transition from heel strike to foot flat.

A second option which works really well is retraining hip control to reduce this impact noise during stance. I love using single leg stance on the wall to teach patient's how to balance on one leg with their hip staying underneath their pelvis. After completing this exercise, patient's normally report that their body feels lighter when their foot hits the floor.

After walking barefoot, I assess the footwear they prefer to walk in for the level of rigidity to determine if the amount of medial arch control matches their functional capacity and if the shoe has enough flex to allow for a foot rocker. Sometimes patient's have shoes which are so stiff that there is no opportunity to roll through the foot even if they know how. Analysis of footwear and tread is the topic for another discussion. For now, just remember that the foot behalves like the shoe it lives in.

Q2: When your foot hits the ground, which part of your leg do you think about?

This question has become more important to my assessment recently. Almost always, the patient tells me they feel their injured body part when their foot hits the ground, even if that part is not the main focus of the particular phase of gait. This is a big problem. If you feel your knee as soon as you touch the floor, you will never successfully transfer energy through the knee as you progress into mid stance or swing. After my patient tells me what they feel, the next question is "does that body part feel painful, heavy, swollen, weak or absent? How does it feel different from the other side?"

A swollen knee feels a bit absent, a stiff knee feels rigid, a painful knee feels guarded, and a normal knee feels strong, normal or like nothing. Give your patients time to think about what they are feeling and allow them to use any words they like to describe how they feel different from side to side. When you do, they often lead you towards the therapeutic exercises which are needed to normalise the difference.

How does it feel compared to the other side?

In early stages of gait retraining after injury or orthopedic surgery, it is important to continually bring the patient back to the other side so that they develop the awareness of left vs right, affected vs normal. As mentioned above, it helps guide treatment direction for return to independent gait.

In chronic injuries, if patients have not spent time thinking about their gait, they can develop efficient yet unhelpful compensation patterns. When this occurs, asking the patient in what way they feel different from side to side, and then asking if they can make them feel the same, can often be enough cueing to encourage them to normalise their compensation. Sometimes its requires more work, but definitely a good place to start and see how malleable a compensation pattern is.

Q3: When your foot leaves the ground, which part do you push off?

The question allows you to address 3 major components of efficient gait:

- Medial arch control

- Push off through great toe extension with ankle plantar flexion

- Hip extension from late stance into swing.

Medial arch control is important to allow for us to transfer our weight into our toes for push off. If you spend too much time in the lateral aspect of the foot then effective push off isn't possible. These patients look like they are trying not to weight bear on their medial arch and instead create a inversion force at the ankle which can transfer up to the lateral knee.

Snapping quickly from the lateral foot to first toe can cause the medial longitudinal arch to collapse. Often these patients progress from the hind foot to forefoot with increased tibial/full leg external rotation and then swing through ankle dorsiflexion/eversion and hip extension/abduction rather than pushing through the big toe and using the calf.

Striking very heavily through the heel with the leg stretched far in front can mean that the patient progresses over the foot with neutral rotational alignment but never pushes into hip extension for swing. Even though they push off a leg, that leg is not truely underneath them in mid stance and therefore doesn't progress into hip extension. These patients often require hip extension training and more calf strength.

Below are two exercises for isolated calf and ankle training. The first is a calf raise with shoulders on the wall, which is great for teaching patients to strengthen their calf muscles while increasing vertical lift. That means, not leaning forward during a calf raise and it is awesome for medial gastrocnemius training.

The second is alignment retraining for patients who spend too much time on their lateral longitudinal arch during gait.

Q4: Can you stand on one leg without shifting your shoulder too far over your hips?

I'm a stickler for retraining gait without excessive lateral shift. We just can't afford to spend so much energy shifting side to side when we should be progressing forward. Patients who have increased lateral shift or don't shift to the side by have a trendelenberg sign. need to learn to stand on one leg again while controlling the distribution of their weight.

There is a simple exercise for re-education of this strategy. Stand facing a wall with hands on the wall shoulder width apart and feet hip width apart. First start to balance on you stronger side and notice how much you shift your shoulders in relation to your hands. You should be able to maintain weight on the opposite hand and prevent the shift. We need to learn to stack them all vertically on top of each as best as possible. Once looking at the better side, try this balance test on the affected side and you'll be surprised how much lateral shift to the standing leg occurs. Normalise this and gait will follow.

Q5: What are the arms doing?

Patients have difficulty learning how to regain their trunk rotation and arm swing, especially if they have been on crutches or a cane. When first progressing of their assistive devices, patients continue to walk as though they are still holding onto something. Locking that arm down prevents trunk rotation, which will impact pelvic rotation and progressing of the legs.

The video above is really interesting because this particular patient was hit by a car as a pedestrian and fractured her right tibia and fibula and dislocated her left shoulder. So she was not able to go on crutches for the lower limb injury due to her shoulder and instead was managed with an internal fixation for the tibia, WBAT with a crutch in the right hand (same side as the leg) and conservative management for the left shoulder. She has done so well managing with this sub-optimal use of a crutch for balance but when progressing off the crutch, demonstrated an interesting distribution of weight.

Q6: Where do you look?

Stop looking at the floor. When you're outside and you need to look at obstacles ahead, people around us, cars and other moving objects and your visual system needs to be available for processing the world around us. So please stop looking at your feet and the ground right in front of you. Before you were injured, you didn't look at your feet so please don't practice that now.

The above six questions are just a few that I go through with my patients while breaking down their gait pattern. I try to use as many external cues as possible and not talk about specific muscles because the ultimate goal is not to think while walking. Before they became injured, they never thought about how they walked or their injured body part. Walking was an automatic movement they learnt in childhood development. It is not natural to devote a large amount of conscious thought to walking. Returning to a relaxed state of reciprocal and alternating effortless gait is the end goal gait retraining.

To remove the burden of injury, we need to learn to move with a sense of lightness and freedom. When our patients achieve this, they will find their stride.

Sian