Calving it up

After a long pause from clinical life, during which I delved deep into the research archives, I have become immersed again in clinical practice. The beauty of this break is that I am now able to make changes to my clinical practice based on all the information I studied over the past 2 years. Part of this change is allowing myself to expand assessment routines and rehabilitation programs to accomodate for this new understanding of clinical reasoning.

In making these changes I needed to first acknowledge that I am, as much as any of us are, susceptible to falling into patterns and routines. I believe we have to. It is the only way we can conserve mental energy for the more complex tasks of our profession. But, what if over time, these same routines which make us more efficient, more enabled to hunt for the finer details, and more skilled at solving the complicated problems, actually distract us from focussing on what is important from the beginning? By this I mean educating our patients about the baseline biomechanics for normal function.

After researching the contributing factors to dynamic balance and the construct of the Star Excursion Balance Test, I was reminded by this idea that phase I of rehab is all about tissue healing and laying the foundation for later stages of recovery. Whether my patients are recovering from a foot, ankle, knee or hip injury, many of them just don't know:

- That walking up stairs requires you to control anterior tibial translation and essentially a momentary single leg squat.

- That walking down stairs requires control of weight bearing ankle dorsiflexion and calf length.

- That learning how to run again requires enough calf strength for push off.

- That limping or wearing a boot stiffens your ankle and shortens your shin muscle (tibialis anterior).

Unless we tell them from the beginning, that the foot and ankle and calf is biomechanically fundamental to their recovery even though they have a knee/hip injury, they won't know. And sometimes it doesn't require a lot of work to maintain dorsiflexion range, calf length, balance and strength etc, and sometimes it does. So instead of waiting to train them more functionally in phase II and III, start in phase I as much as the tissue healing allows.

A brief example

The videos below show a past patient who presents with metatarsalgia in the second toe. Her problem had developed while attending a fitness class which involved a lot of planks, lunges and single leg balance. As you can see from these videos, this patient struggles enormously with dynamic balance control through her knee and hip, and the outcome of this is to overload the metatarsophalangeal joints. Her second toes also extends slightly further than her first toe, making is a point of weight bearing during toe extension with ankle plantar flexion. When I first assessed this patient, I made a conscious note that our treatment should eventually address all the contributing factors leading to overload in 2nd toe extension, such as limited ankle mobility, tightness through plantar fascia soft tissue structures, and inefficient dynamic balance control mechanisms.

At first, the patient did not understand why I cared so much about the rest of her leg when the pain was clearly isolated to the base of her second toe. Only after showing her how challenged her balance truely was, did she understand the confounding nature of her current exercise routine.

The exercises below cover my go-to's for early ankle control and mobility. It is not an exhaustive list, but a solid start. They aren't fancy, or new, but for me, super important to ensure that everyone can do. The underlying trend is making sure we take the time to prepare our patients for their higher level recovery and set them up to win. No matter the injury, these are principles that are essential for normal biomechanics of gait.

- Calf strength: I generally begin with double leg calf raises facing a wall with hands on the wall. The idea is to encourage patients to raise straight up on their toes, keep their heel bones in line with the rest of the foot (not roll onto the outer toes) and to balance their hand pressure evenly on the wall.

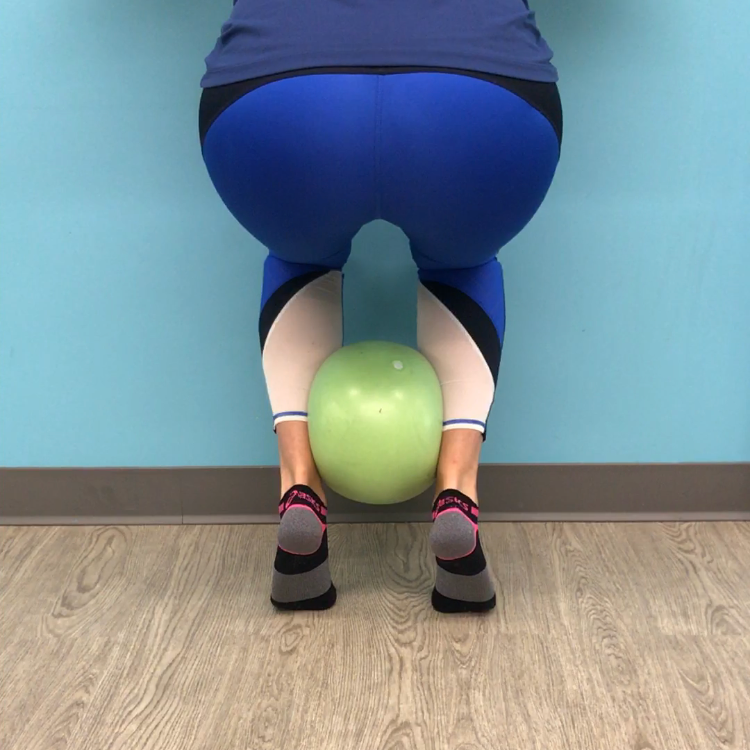

- Regression: If this is too hard some variations include placing a ball between the legs above the ankle to bring them into alignment, or turning them around and putting their shoulders on the wall.

- Progressions: The third image shows how a double leg calf raise can be progressed into a squat while using the ball to maintain heel alignment. You can also progress the load by moving to one leg. What is important to remember with single leg calf raises is developing enough pelvic awareness and control to keep the trunk appropriately balanced over the ankle.

- Ankle mobility/calf length: I try to assess everyone's ability to perform ankle plantar flexion and weight bearing ankle dorsiflexion range with a bent and straight knee as I think these movements are all important to gait. Image 4 & 5 show the difference between a straight and bent knee calf stretch, which is what I call them, and image 6 is an easy plantar flexion stretch. If you don't have plantar flexion range, getting high up in a calf raise is tough.

- Progression: the last two images show weight bearing ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. The movements can be done individually, or as you'll see in the video, as a continuous rocking movement in quadruped. This is definitely a more advanced exercise that requires full painfree knee and hip flexion as a prerequisit.

Here are the exercises as short videos.

Summary

The first aim for this blog was to highlight how we can break down the components of a dynamic balance test such as the SEBT, or understand the requirements for normal gait and stair navigation. The second was to emphasise the importance of making sure that our early stages of rehabilitation allow for sufficient time to help our patients develop the range of movement, muscle length and neuromuscular control to allow them to be successful when integrating these components together. I recognise that these exercises aren't radically new or fancy, heck they can be just down right boring, but when done right and combined with the education as to why, they can be hugely impactful.

SS

References:

Clagg, S., Paterno, M. V., Hewett, T. E., & Schmitt, L. C. (2015). Performance on the modified star excursion balance test at the time of return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 45(6), 444-452.

Cuğ, M. (2017). Stance foot alignment and hand positioning alter star excursion balance test scores in those with chronic ankle instability: What are we really assessing?. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 33(4), 316-322.

De La Motte, S., Arnold, B. L., & Ross, S. E. (2015). Trunk-rotation differences at maximal reach of the star excursion balance test in participants with chronic ankle instability. Journal of athletic training, 50(4), 358-365.

Dill, K. E., Begalle, R. L., Frank, B. S., Zinder, S. M., & Padua, D. A. (2014). Altered knee and ankle kinematics during squatting in those with limited weight-bearing–lunge ankle-dorsiflexion range of motion. Journal of athletic training, 49(6), 723-732.

Gabriner, M. L., Houston, M. N., Kirby, J. L., & Hoch, M. C. (2015). Contributing factors to star excursion balance test performance in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Gait & posture, 41(4), 912-916.

Gribble, P. A., Hertel, J., & Plisky, P. (2012). Using the Star Excursion Balance Test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. Journal of athletic training, 47(3), 339-357.

Gribble, P. A., Kelly, S. E., Refshauge, K. M., & Hiller, C. E. (2013). Interrater reliability of the star excursion balance test. Journal of athletic training, 48(5), 621-626.

Hertel, J., Braham, R. A., Hale, S. A., & Olmsted-Kramer, L. C. (2006). Simplifying the star excursion balance test: analyses of subjects with and without chronic ankle instability. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 36(3), 131-137.

Earl, J. E., & Hertel, J. (2001). Lower-extremity muscle activation during the Star Excursion Balance Tests. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 10(2), 93-104.

Hyong, I. H., & Kim, J. H. (2014). Test of intrarater and interrater reliability for the star excursion balance test. Journal of physical therapy science, 26(8), 1139-1141.