Sleep More, Hurt Less

This week we are excited to welcome guest writer and soon-to-be Physical Therapist Sara Suddes to Rayner & Smale. I met Sara while teaching at UCSF and was excited to hear about the topic for her final-year evidence based practice presentation.

Before transferring in PT school, Sara worked as a newspaper reporter. Sara has spent many months researching the bidirectional relationship between sleep and pain and has put her brilliant writing skills to use to share with us her thoughts about sleep and pain.

It's a real chicken and egg conundrum

What comes first – poor sleep or pain? Does the former cause the latter? Or does the presence of pain simply cause sleepless nights? Is the relationship cyclical? Or does a third factor – stress, anxiety, karma – influence both?

Many investigations have shown a clear relationship between poor sleep and pain, and the two are often comorbid conditions, but until recently, the directionality of the relationship between sleep and pain was unclear. Trying to come up with new ways to help my patients banish their pain, I recently set out in search for the answer to this quandary.

But before I tell you what I found, let me tell you why sleep and pain matter to me – and why I think you should care, too. When it comes to health, everyone, including myself, seems to be looking for a magic bullet. But there are no quick fixes – and being happy and healthy can be really hard work. It can be incredibly overwhelming, and sometimes it’s easier to just throw our hands up in the air and put if off until tomorrow. Sleep is a way of taking care of yourself that should be easy. When there are a million things to try, it’s something simple to start with, and stick with. Inertia can be a powerful wave, and if just one thing helps, others will follow.

When I look at my best days, what they have in common is that, on those days, I did something – anything! – to take care of my body, my brain, and my heart. I learned something new, probably worked up a sweat at some point, got a little sun on my face, laughed a lot, and started it all off by waking up rested and ready to take on the day. Those are my best days, and I feel that it’s our job as physical therapists to help our patients get back to living their best days.

As physical therapists, we’re taught the mechanics, the science, the physiology: We can mobilize a neck, correct posture, and reinforce it with a great home exercise program, but if we want to set our patients, and ourselves, up for success in the long run, we have to address the big picture.

The impact of poor sleep on pain

My cat Walter, who gets plenty of sleep.

So I looked at the effects of poor sleep on neck pain. I choose neck pain because its impact is staggering. Globally, neck pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal health problems reported in the general population, with a mean lifetime prevalence of 50 percent, and one-month prevalence of 25 percent (Fejer et al., 2006). Neck pain is one of the most significant contributors to years lived with disability, (Vos et al., 2010) and leads to a variety of activity limitations impacting quality of life. An estimated $90 billion is spent annually on the diagnosis and management of low back and neck pain, with an additional $10 to $20 billion spent on associated productivity losses (Cote et al., 2008).

Meanwhile, good sleep is out of reach for many of us – 33 percent, to be exact, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than a third of American adults are not getting enough sleep on a regular basis – “enough” meaning seven hours each night (Watson et al., 2015). If you are one of the lucky few able to prioritize catching your Zs over catching up on the news or the latest episode of House of Cards, good for you! Please share your secrets to success in the comments below. We’re dying to know, because less sleep is associated with a multitude of comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, and stroke – not to mention dark under-eye circles and a matching bad attitude. Poor sleep has also been associated with a decrease in memory, lifespan, attention, learning, and metabolism, and an increase in inflammation, fatigue, stress, and depression. And pain.

Sleep is a natural muscle relaxant

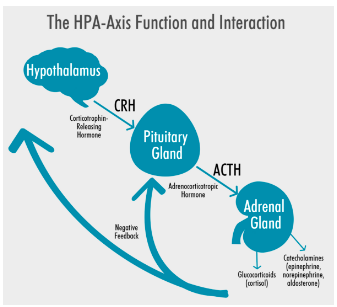

So when we’re treating pain, why not make sure we’re talking to our patients about sleep alongside diet, exercise, body mechanics, etc.? One researcher aptly described sleep as “a natural muscle relaxation agent” (Kaila-Kangas, 2006), and I couldn’t agree more. Basically, chronic sleep deprivation, or troubled sleep – characterized by difficulty falling asleep or frequent awakenings – is a form of stress. Stressful situations trigger the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, the body’s stress response, to kick into high alert. When the HPA axis activated, a cascade of events take place, resulting in elevated cortisol levels. Intermittently, more cortisol is great if you need to quickly mobilize energy stores to outrun an attacker or save a baby cat from a burning building. But chronically elevated cortisol levels can wreak havoc on the body’s tissues, and disturbances of HPA function are associated with new onset of chronic widespread pain. On the flip side, the therapeutic effects of sleep include decreased muscle tone, and increased relaxation and recovery.

As I delved deeper into the research, I found that poor sleep is not only a precursor, but also a predictor, for the development of future neck pain. And by “delve deeper,” I mean that I spent about six months of my life performing a systematic review and meta-analysis of the existing literature examining this topic. Leading to many sleepless nights…

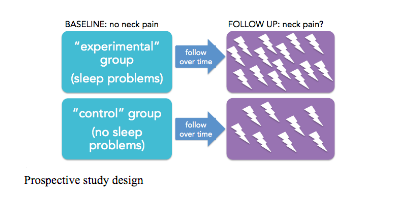

I took a look at all the existing prospective studies – just three, all conducted in Scandinavian countries where sleep rhythms are challenged by entire seasons when either daylight or darkness is scarce (Eriksen et al., 1999; Mork et al., 2013; Kääriä et al., 2011) – examining the relationship between poor sleep and neck pain, specifically, whether the former is responsible for the latter. Initially, participants in these studies were asked if they had neck pain. Those who did were politely thanked for their time, and then subsequently booted out of the study. Those who did not – i.e. those who claimed they had healthy necks – were invited to continue on. The owners of those healthy necks were then asked about their sleep. Some said their sleep was poor. Others said it was fine. The researchers let those people go about living their lives for a few years, and then checked back in down the line. Participants were again asked about their necks. Some had developed pain. Uh oh.

I ran some stats. So many stats – odds ratios, risk ratios, Q-statistics for heterogeneity. But even before I started crunching the numbers, I had a sneaking suspicion about what to expect. As it turns out, the numbers didn’t lie. I found that participants were more likely to develop neck pain down the line if they reported suffering from poor sleep at baseline. In fact, the odds of a “poor sleeper” for developing neck pain were 1.79 times the odds of their restful peers. Essentially, if you’re sleeping poorly, you’re more at risk for developing pain than if you’re sleeping like a baby.

So, as you can see, sleep matters! We need to consider sleep as one factor among many, including diet, physical activity, etc. that contribute toward quality of life. Clinically, these findings suggest that sleep disruption may hold significant promise as an intervention target in efforts to prevent and treat chronic pain. Knowing all this, PTs should keep in mind that talking to their patients about sleep is just as important as talking to them about doing their exercises when it comes to addressing pain.

It all boils down to: Sleep more, hurt less.

About Sara Suddes

Sara is two months away from graduating with her DPT. She is a former newspaper reporter who decided it's never too late to start all over from scratch. She'd rather be outside than sitting at a desk.

Previous blogs about sleep & pain:

Are we understanding the importance of sleep?

Can we pick the clinical signs of excessive sleepiness and sleep disorders?

The bidirectional relationship between sleep disorders and pain conditions.

The neuromatrix of pain overlaps with the functional neuroanatomy of sleep.

References:

CDC Press Releases. CDC. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0215-enough-sleep.html. Accessed November 9, 2016.

Côté P, van der Velde G, Cassidy J et al. The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in Workers. Spine. 2008;33(Supplement):S60-S74. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e3181643ee4.

Eriksen W, Natvig B, Knardahl S, Bruusgaard D. Job Characteristics as Predictors of Neck Pain. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 1999;41(10):893-902. doi:10.1097/00043764-199910000-00010.

Fejer R, Kyvik K, Hartvigsen J. The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. European Spine Journal. 2005;15(6):834-848. doi:10.1007/s00586-004-0864-4.

Kääriä S, Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E, Leino-Arjas P. Risk factors of chronic neck pain: A prospective study among middle-aged employees. European Journal of Pain. 2011;16(6):911-920. doi:10.1002/j.1532-2149.2011.00065.x.

Kaila-Kangas L. How consistently distributed are the socioeconomic differences in severe back morbidity by age and gender? A population based study of hospitalisation among Finnish employees. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006;63(4):278-282. doi:10.1136/oem.2005.021642.

Mork P, Vik K, Moe B, Lier R, Bardal E, Nilsen T. Sleep problems, exercise and obesity and risk of chronic musculoskeletal pain: The Norwegian HUNT study. The European Journal of Public Health. 2013;24(6):924-929. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt198.

Vos T, Flaxman A, Naghavi M et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163-2196. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61729-2.

Watson N, Badr M, Belenky G et al. Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: A Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. SLEEP. 2015. doi:10.5665/sleep.4716.