Rayner & Smale Launch Pad

As 2017 draws to a close and we begin to reflect on what this year has meant for our blog, it is valuable to understand our audience. Rayner & Smale is written for physiotherapists and clinicians from all paths and levels of experience. We definitely receive more feedback from newly graduated therapists who are trying to navigate their way through private practice, musculoskeletal or orthopedic physiotherapy and settle into their new careers. To be part of that learning experience and clinical journey is such a pleasure. This blog is a starting point to unravel some of our most-read, and most-applicable content from the past 4 years. We believe it forms a foundation for learning about physiotherapy before narrowing into the finer detail of specific body regions or conditions.

Below is a list of ideas of areas you can focus on improving as a new graduate physiotherapist - essentially these are the areas/skills that I was directed to enhance first before my knowledge base and clinical reasoning could become more injury-specific in focus.

Master the Subjective assessment

The subjective examination is often undervalued in the assessment and management of a patient. In my opinion, it is the most crucial aspect of the examination as it determines the severity, irritability and nature (SIN) of the patient’s condition. Good questioning leads to the formation of primary and secondary hypotheses, possible methods of treatment and likely prognosis of the injury.

My two top tips for the subjective assessment are:

- Take time to listen to your patients and truly understand their story.

- Always remember that they are the best source of information you have to help you solve their problem.

Read one of our previous blog on the structure of a subjective assessment here, which provides a great outline for the format for a subjective assessment to help you understand what the patient’s problem is, and questions to reduce the risk of missing sinister pathology.

Using the WHO-ICF is a great way to break down the impact on quality of life and to help set goals which are achievable and meaningful to each individual. This is based on the physical impairment, participation limitation and activity restrictions.

Along with understanding the impact of the problem on quality of life, I try to keep an open-mind about how the pain may lead to social isolation and disconnection from relationships.

I always question if the change I wish to see in my patients will actually lead to improved health outcomes. I generally aim to change their pain and find the source of symptoms (thats always so interesting and like being a detective), but I also focus on return of function, return to activity, and return to work. This is what often contributes more to their quality of life.

Plan out your sessions

Writing sessions plans can be incredibly daunting as a new grad, but it is a helpful way to outline your projected treatment for a particular condition and outline how treatments may differ based on the condition, patient population, and their goals for discharge.

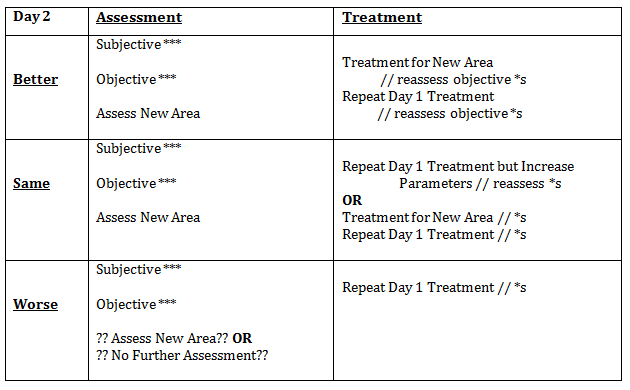

A session plan can be a simple as summarising the key assessments and findings from day 1, listing out what you didn’t get round to completing and how much of a priority it is to complete in session 2 or 3. I also use my session plans to leave myself reminders of where to go next.

Alicia wrote a fantastic blog showing a structure for writing out session plans, which we both used at university while studying our Masters.

Movement diagrams

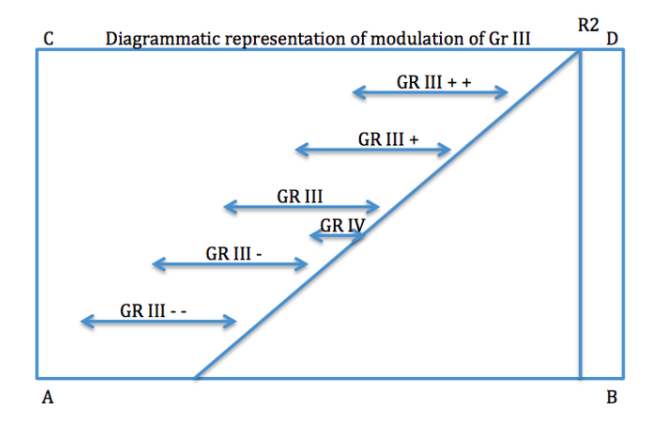

Movement diagrams continues to be one of our most popular reads, and yet it is a quick and simple one too. When it came to learning the concept of movement diagrams at university, I struggled to appreciate their utility because they weren’t based on real patients and real assessments. Now I use them daily during every assessment of movement and when performing a manual tasks.

Although movement diagrams were taught as a way of objectively documenting a subjective assessment of movement or a manual test, they serve a far greater purpose to develop your pattern recognition skills and to assist with developing a strong memory for how each of your patients presents.

Why do we use movement diagrams?

The most important reason is to know what we are feeling. Movement diagrams are essential to separate the different components of what is felt when examining movement and to allow you to analyze the effect that treatment is having on signs and symptoms.

"Movement diagrams are essential for to understand the relationship that the various grades of movement have to the patient's abnormal joint signs" (Maitland., 2005. p. 446).

Compiling this information in the form of a movement diagram enabled me to understand the primary cause of the movement abnormality and allow me to carefully select and apply treatment techniques to the problem.

Question for Red flags

It is our professional responsibility to be able to identify those who required further medical examination or treatment. Identifying these patients begins during the subjective examination when we question for the presence of red flags.

"‘Red flags’ are risk factors detected in patients’ past medical history and symptomatology and are associated with a higher risk of serious disorders causing pain compared to patients without these characteristics. If any of these are present, further investigation (according to the suspected underlying pathology) may be required to exclude a serious underlying condition, e.g. infection, inflammatory rheumatic disease or cancer" (Van Tulder et al., 2006, p. S172).

Here is a outline of the various red flags per body region we can expect to include in our assessment.

Practice your PPIVMS and PAIVMS

I was always told this but never did it. During my masters I had to practice over and over again and I was often practicing my manual handling on the weekends with my friends or if they were busy, my poor husband. The more you practice and get used to feeling necks and backs and getting feedback from those people, the better your handling becomes. If you only treat during work hours, without practicing, you lose the ability to be creative and work on techniques you’re not as strong at.

Designing HEP that work using goal setting and collaboration

This is one key area of physiotherapy treatment that is unique among us all, and when it is given to a patient in a way that is meaningful and impactful for them, it's power in recovery is unmeasurable. This component is the part we most commonly overlook or leave until the end of our sessions when time is scarce, but is the most important part to include - patient education.

The most important thing for improving patient compliance is patient understanding. Therefore designing a HEP that work comes down to your ability as an educator to explain to someone why they need to complete these exercises in their own time, what are ways they can measure success both in-session and between-sessions and what will be the cues that suggest progression is possible at the next review.

Set personal and professional goals

I’ve had the pleasure of informally mentoring several clinicians making their way into the field. But more than that, I’ve been guided and molded by excellent mentors, who have played a crucial role in developing my into the clinician I am today. Having a mentor, formal or informal, is an unspoken gem to prevent burnout and promote learning in our profession. My advice, if you don’t feel that there is a mentor within your workplace who will provide formal guidance for your first 2 years, strike up a relationship with a previous teacher or influential person in your life. When I moved to San Francisco in 2015, 5 years into my career, becoming distant from my mentors and having to seek out and build new relationships was challenging. I often felt very alone while I tried to navigate the waters of requalifying in San Francisco. My husband became my mentor and advisor for many issues and while I’ve been able to form relationships with new local physiotherapists, I’m still searching for my mentor and still feel the impact of that absence in my career.

Having a mentor will allow you to set reasonable and achievable goals for the first 12-24 months of your practice. When you leave university it is totally normally to feel overwhelmed and suddenly aware of everything you don’t know. Go on, write that list of everything you want to learn and I guarantee you are setting yourself up for disappointment. There is no way you’ll learn everything you think you need to know in that time frame. And that is ok, you’re still equipped with excellent up-to-date knowledge to help your patients.

Here are a few ways to think about goal setting for your personal and professional growth:

- What hobbies do you love that you wish to try continue with the transition to full time work?

- What aspects of your patient care makes you feel nervous - interview, documentation, assessment etc? These are the areas you develop first.

- Don’t focus on conditions or body parts until about 6+ months in - you need to spend a long time mastering the routine of assessment and interviewing and developing strong habits that help you develop pattern recognition skills.

- What continuing education courses would you like to attend and why?

- Is there a post-graduate course, residency or other official education program you would like to enroll or apply for and what are the requirements of these?

More of our blogs I think are worth reading:

After reading this blog you may be enticed to keep following our learning and growth as a blog, but it can be daunting to understand where to begin in our archives. Here are 26 which I believe are a wonderful place to start. In no particular order, you can read one every 2 weeks for your first year of practice.

Upper limb:

Lower limb:

Spinal:

Neurodynamics:

Pain science and education:

Other:

Good luck and keep learning. Sian :)