Seronegative spondyloarthropathies & inflammatory low back pain - Part 1

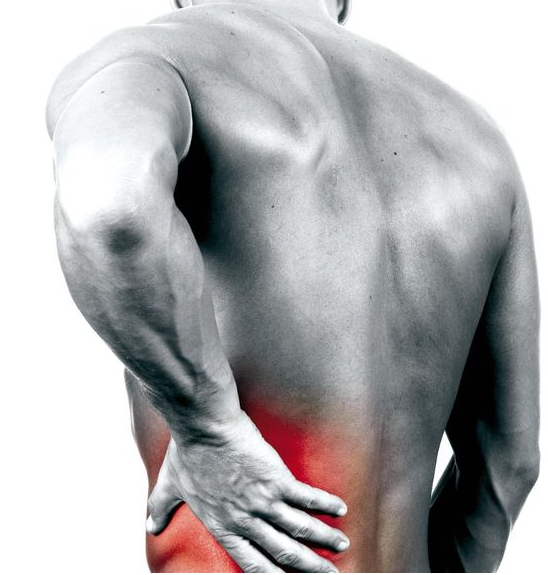

If I asked you what percentage of patients with low back pain have a 'mechanical problem' or 'non-specific problem' your answer might be about ~85%. To my knowledge that answer fits with what we know about the prevalence of serious and sinister pathology masquerading as low back pain. What we don't often talk enough about is that remaining ~15%. Many of these people will have 'specific low back pain' and then there are those who have serious pathology and medical disorders that contribute to back pain (<5%).

It is our responsibility to determine if a patient is suitable for physiotherapy, and the majority of the time they will be. We do however, need to identify those that require further medical examination and treatment. Identifying these patients begins during the subjective examination when we question for the presence of red flags, family history and features of non-mechanical or inflammatory pain mechanisms. In previous blogs we've discussed red flags and visceral pain, and for this blog we are going to focus on inflammatory low back pain. The question I'd like to ask you is...

How confident are you in recognising the outlier presentations & those with inflammatory low back pain?

Do you know which conditions come under the umbrella of seronegative spondyloarthropathies?

Does the presence of these conditions impact your treatment approach?

Don't be alarmed by these questions - I may not have known how to answer them thoroughly until a few months ago. However, as part of my requalification process for California, I've been required to study diseases of the Integumentary system, Metabolic system and Endocrine system. Each has taught me a lot about applying physiotherapy knowledge to non-musculoskeletal conditions & differential diagnosis.

The purpose of this blog is to share some of this new knowledge with you about seronegative inflammatory disorders and spondyloarthropathies. Taking a look at the pathophysiology and cardinal signs, the classification of inflammatory low back pain, and the diagnostic criteria for these condition.

What does 'seronegative' & 'spondyloarthropathy' mean?

Spondyloarthropathies are a group of related, yet, phenotypically distinct inflammatory disorders. Spondyloarthropathies include ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis (also known as irritable bowel disease), and undifferentiated arthritis.

Spondyloarthropathies are known as seronegative inflammatory disorders, which means they don't have the same phenotype (cause of auto-immune disorder) as Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid arthritis is caused by the presence of rheumatoid factor, where as, these seronegative conditions (i.e the absence of rheumatoid factor) have been linked to the presence of major histocompatibility complex class 1 antigen HLA-B27 (Zochling & Smith., 2010). This group of conditions are generally "characterised by sacroiliitis with inflammatory back pain, peripheral arthropathy, absence of rheumatoid factor and subcutaneous nodules, enthesitis/enthesopathy, extra-articular or extra-spinal involvement, including of the eye, heart, lung and skin" (Ehrenfeld., 2012, p.136).

Each of these conditions fulfil the criteria for diagnosis as a spondyloarthropathy based on the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) Classification. The ESSG is a classification tool used and recognised worldwide for the diagnosis of these conditions. Someone will be diagnosed as having a spondyloarthropathy if they have inflammatory spinal pain and any of the following:

Image courtesy of Google Images, retrieved March 30th, 2016

- Positive family history

- Psoriasis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Acute diarrhoea, urethritis or cervicitis preceding the onset of arthritis

- Alternating buttock pain

- Enthesopathy

- Radiological sacroiliitis (Zochling & Smith, 2010).

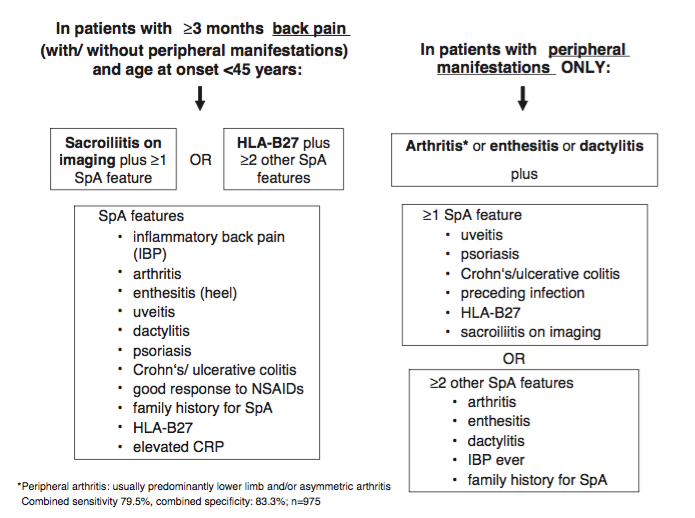

As you can see the ESSG is quite a broad classification tool and doesn't identify which main type of spondyloarthropathy is present. To make this more detailed Rudwaleit and colleagues (2011) conducted a study examining the International Classification Criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. This became known as the ASAS Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society. From this study they created a clinical framework that include both axial and peripheral symptoms in diagnosis. Based on this criteria below, the diagnosis of spondyloarthropathy can be made with a sensitivity of 77.8% and specificity of 82.9%.

(Rudwaleit et al., 2011, p. 29).

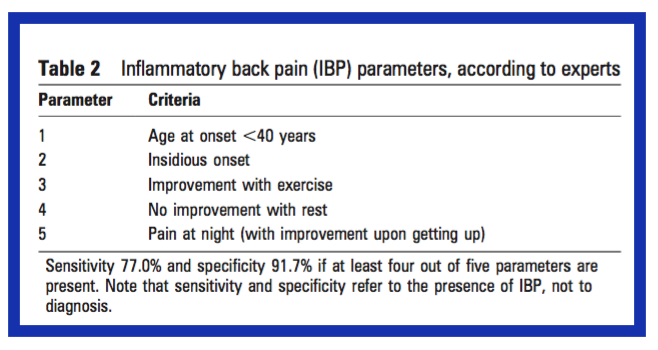

clinical features of Inflammatory low back pain

One of the recurrent themes in both the ASAS and ESSG is the presence of inflammatory low back pain longer than 3 months. The next question is - How would you decide if someone has inflammatory low back pain? Lucky for us, there have been other studies which compare inflammatory to non-inflammatory back pain, and provide us with the clinical criteria for diagnosis (Sieper et al., 2008).

Q: What are the clinical features of inflammatory low back pain?

A: There are 5 key features that specialists feel are highly indicative of this condition.

(Sieper et al., 2008, p. 786)

Interestingly, even though these are the 5 key features, other features that were assessed and found present were dactylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, HLA-B27 positive, and radiographic evidence according to the New York criteria. All of these conditions have been mentioned in the ASAS criteria, but we might look past them if we only ask about the five components above.

With patients who suffer from inflammatory back pain, there is also higher frequency of the following signs & symptoms:

- Age onset < 40

- Back pain > 3 months

- Insidious onset

- Morning stiffness

- Improvement with exercise

- No improvement with rest

- Alternating buttock pain

- Pain at night.

So there are two parts to the assessment. First, determine if you patient has inflammatory back pain and second, determine if they have a spondyloarthropathy. There are several classification tools used in the literature that help us further expand on our diagnosis; the New York Classification, the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group Classification, The international criteria and CASPAR. In the second part of this blog we will discuss altering our assessment to question for all of these factors, but first, let's take a look at each of the conditions that come under the term seronegative spondyloarthropathies.

WHAT ARE THE CARDINAL SIGNS?

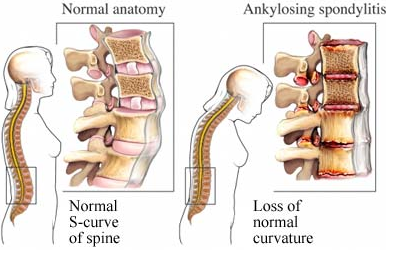

Ankylosis Spondylitis AS

Of the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, AS is both the most prevalent and debilitating. The primary complaint is inflammatory low back pain, but patients may also suffer from enthesopathy, peripheral arthritis and extra articular manifestations (Zochling & Smith, 2010). Over 90% of AS patients are HLA-B27 positive and it is thought to be a male predominant condition. Diagnosis can be made clinically from the identification of inflammatory low back pain and use of the New York Classification Criteria (Zochling & Smith, 2010). One point to make about this current classification tools is that they only include radiological evidence of sacroiliitis and none of the classifications have been updated to include MRI. MRI is currently thought to be more sensitive in detecting early inflammatory changes compared to XRAY and while it is more costly, it is going to provide better information early on (Akgul & Ozgocmen, 2011; Zochling & Smith, 2010).

New York Classification Criteria:

- Low back pain for at least 3 months that improves with exercise and does not improve with rest.

- Limited spinal movements forwards, backwards and sideways (i.e. 3 planes of movement).

- Reduced chest expansion for normative age and sex values (generally <2.5cm measured at forth intercostal space).

- Bilateral sacroiliitis grade 2-4 or unilateral sacroiliitis grade 3 or 4 on XRAY.

- The diagnosis of AS is made if there is sacroiliitis and any one of the previous 3 points (Khan, 2002).

Image courtesy of Google images, retrieved March 30th, 2016.

Clinically, patients will present with aching or pain over the buttock region, stiffness or loss of spinal range of movement, and pain which eases with activity and become worse with rest. The pain will generally respond well to NSAIDS and can be unilateral, bilateral or alternating from side to side (Ehrenfeld, 2012). Another point to note is that people with AS are also more prone to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, which unfortunately translates into a slightly higher mortality rate when comparing people with AS to those without (Zochling & Smith, 2010).

Psoriasis

“Psoriasis is a common, chronic, inflammatory, multi-system disease with predominantly skin and joint manifestations affecting approximately 2% of the population” (Gottlieb et al., 2008, p. 826). Clinically, psoriasis manifests as inflammation of the skin and can result in scaling, disfiguring and red painful plaques which can become pruritic. Psoriasis is associated with several other medical comorbidities: autoimmune diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, lymphoma, non melanoma skin cancer, and psoriatic arthritis (Gottlieb et al., 2008).

Psoriatic Arthritis PsA

Clinically, patients with psoriatic arthritis have enthesopathy, which is inflammation at the site where the tendon or ligament attach to bone; and dactylitis, which is a combination of enthesopathy and synovitis involving the whole digit. One of the cardinal signs of this condition is the development of nail dystrophy and deformity of the hands or feet. Psoriatic arthritis can affect single or multiple joints (Goodman & Fuller, 2014).

Inflammatory synovitis results from lymphocyte infiltration into the synovium. Edematous granulation tissue develops in the synovium and extends along the contiguous bone. Later the synovium becomes thickened and hypertrophied. At this time, eroded articular margins appear and in severe cases, the joint space can be filled with dense fibrous tissue (Goodman & Fuller, 2014).

Differentiating psoriatic arthritis from other seronegative inflammatory joint disease can be challenging as there is no current validated, sensitive and specific screening tool available for dermatologists to use. There is however a cluster of signs that do assist with clinical reasoning (Menter et al., 2008). One example of this is the CASPAR, which states that a patient must have an inflammatory articular disease with 3 or more of the following dot points. If they meet the criteria below, a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis can be made with a specificity of 98.7% and sensitivity of 91.4% (Taylor et al., 2006).

- Evidence of current psoriasis, personal history of psoriasis or family history of the disease.

- Typical psoriatic nail dystrophy on physical examination.

- A negative test result for the presence of rheumatoid factor (RF).

- Current dactylitis, defined selling of the digits or a defined history of these features.

- Radiological evidence of juxta-articular new bone formation or ill-defined ossification near joint margins of the hand and foot.

Reactive arthritis ReA

As the name suggests, reactive arthritis often is triggered by a preceding infection. Often this infection is enteric or eurogenital (Zochling & Smith, 2010). I remember my first case of ReA as a physiotherapist, in a 13 year old girl who got terribly sick overseas from food poisoning and developed reactive arthritis in her elbow following the event. She was managed under a Rheumatologist and responded well to NSAIDS. Once her stomach had healed, her elbow soon followed. Some studies suggest that the risk of developing ReA is 50 times higher in individuals who are HLA-B27 positive (Zochling & Smith, 2010). Usually the arthritis will occur within the first month following exposure to infection (Khan, 2002).

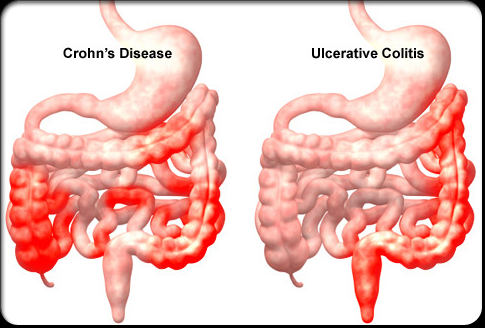

Inflammatory bowel disease IBD

Image courtesy of Google Images, retrieved March 30th, 2016.

Under the category of IBD we often encounter Crohn's disease and Ulcerative Colitis. IBS is documented throughout the literature as having a strong association with axial spondylitis, peripheral arthritis and sacroiliitis (Zochling & Smith, 2010). The link between IDB and HLA-B27 positive individuals is not as strong as AS and PsA, but there still is some involvement of this phenotype.

Between 17-39% of people with IBD will suffer from extra-intestinal manifestations, with spondyloarthropathies being the most common (Gionchetti, Calabrese & Rizzello, 2015, p. 21). Usually in these patients, spondyloarthropathy is diagnosed after the onset of IBD symptoms. Up to 20% of patients will develop axial arthritis and/or sacroiliitis, with a smaller percentage developing peripheral joint symptoms ( Gionchetti, Calabrese & Rizzello., 2015).

Patients may present to the physiotherapist with a complaint of low back pain, peripheral joint pain and swelling, signs of enthesopathy and even dactylitis. In these patients, the key additional symptoms you are looking for are (red flags):

- Family history of IBD,

- Clinical symptoms of IBD (diarrhea, rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, weight loss),

- Current or previous perianal disease, and

- Anemia (Gionchetti, Calabrese & Rizzello., 2015).

Undifferentiated spondyloarthropathies UdSp or SAPHO

Some references suggest the 5th category is undifferentiated, while others propose SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) (Jadon & McHugh, 2014; Zochling & Smith, 2010). I think the main point to highlight here is that there are other, less prevalent inflammatory disorders that don't fall under the categories of AS, PsA, ReA and IBD, that may still result in inflammatory low back pain. These less common conditions are going to be diagnosed by the Rheumatologist, but its useful to know to look out of other non-musculoskeletal conditions and to question for other symptoms preceding or associated with the patients pain condition.

The images above are of hands of patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. They are included as a reminder that rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis don't come under the term of seronegative spondyloarthropathies.

Image courtesy of Google Images, retrieved March 30th, 2016

Having discussed the diagnostic tools available to determine if someone has inflammatory low back pain, and explored the different conditions known to be seronegative spondyloarthropathies, let's move on to the impact it has on clinical practice.

The second blog discusses how we can change our examination of a patient who we suspect might have an underlying inflammatory disorder and how this may change our treatment or involvement with them.

Sian

References

Akgul, O., & Ozgocmen, S. (2011). Classification criteria for spondyloarthropathies. World J Orthop, 2(12), 107-15.

Brosseau, L., Wells, G. A., Tugwell, P., Egan, M., Dubouloz, C.-J., Casimiro, L., . . . Bell, M. (2004). Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for therapeutic exercises in the management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults. Physical Therapy, 84(10), 934-972.

Davies, R., Symmons, D. P., & Hyrich, K. L. (2014). Biologics registers in rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine, 42(5), 262-265.

Dougados, M., & Baeten, D. (2011). Spondyloarthritis. The Lancet,377(9783), 2127-2137.

Ehrenfeld, M. (2012). Spondyloarthropathies. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 26(1), 135-145.

Gionchetti, P., Calabrese, C., & Rizzello, F. (2015). Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Spondyloarthropathies. The Journal of Rheumatology, 93, 21-23.

Goodman, C. C., & Fuller, K. S. (2014). Pathology: implications for the physical therapist: Elsevier Health Sciences.

Gottlieb, A., Korman, N., Gordon, K., Feldman, S., Lebwohl, M., Koo, J. Y. M., . . . Menter, A. (2008). Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 58(5), 851-864.

Jadon, D. R., & McHugh, N. J. (2014). Other seronegative spondyloarthropathies. Medicine, 42(5), 257-261.

Khan, M. A. (2002). Update on spondyloarthropathies. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(12), 896-907.

Linden, S. V. D., Valkenburg, H. A., & Cats, A. (1984). Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 27(4), 361-368.

Maitland, G. D., Hengeveld, E., Banks, K., & English, K. (2005). Maitland's vertebral manipulation (Vol. 1): Butterworth-Heinemann.

Menter, A., Gottlieb, A., Feldman, S., Van Voorhees, A., Leonardi, C., Gordon, K., . . . Bhushan, R. (2008). Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 58(5), 826-850.

Paparo, F., Revelli, M., Semprini, A., Camellino, D., Garlaschi, A., Cimmino, M. A., ... & Leone, A. (2014). Seronegative spondyloarthropathies: what radiologists should know. La radiologia medica, 119(3), 156-163.

Rudwaleit, M., Van Der Heijde, D., Landewé, R., Akkoc, N., Brandt, J., Chou, C. T., ... & Van den Bosch, F. (2010). The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, annrheumdis133645.

Sieper, J., van der Heijde, D. M. F. M., Landewe, R., Brandt, J., Burgos-Vagas, R., Collantes-Estevez, E., ... & Van Der Linden, S. (2009). New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: a real patient exercise by experts from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS). Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 68(6), 784-788.

Taylor, W., Gladman, D., Helliwell, P., Marchesoni, A., Mease, P., & Mielants, H. (2006). Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: Development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis & rheumatism, 54(8), 2665-2673.

Zochling, J., & Smith, E. U. (2010). Seronegative spondyloarthritis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 24(6), 747-756.