Interpretation of special tests in musculoskeletal examination

Introduction to Research Methods

Research methods is an important topic in evidence-based physiotherapy, although many people are discouraged to learn about it because the material can be boring and dry. But how do we trust the information we read? I remember so clearly the time when Britannia Encyclopaedia was the only source of information I would reference in school assignments. Before the internet or even the intranet, there were books and encyclopaedias. But now, the internet is saturated with articles and its a struggle to access them, digest them and ultimately form an opinion if the results are clinically significant

This is why so much emphasis is placed on using high quality randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews to become more informed about what the research is telling us. Are you daunted by articles that are a minimum for 14 pages long? Are you ever tempted just to read the abstract and conclusion? I definitely have my moments when I fall into that trap.

But wait.... thats why we are forced to take subjects like research methods. To teach us about how high quality articles are written, to understand the psychometric properties of clinical assessment tools and to decide wether the information is worthwhile to remember and disseminate into the community?

So I hope in this blog just to remind you of some of these psychometric properties, such as specificity, sensitivity and likelihood ratios. I've found this personally very helpful to interpret what I read and become more informed by the evidence about best clinical practice. Why do we need to know these values? Because so single test is diagnostic.

"Of course, very few tests can be expected to conclusively rule in or rule out any particular condition but they should add to the index of suspicion which will inform your clinical reasoning process." (Hattam & Smeatham, 2010, p.5).

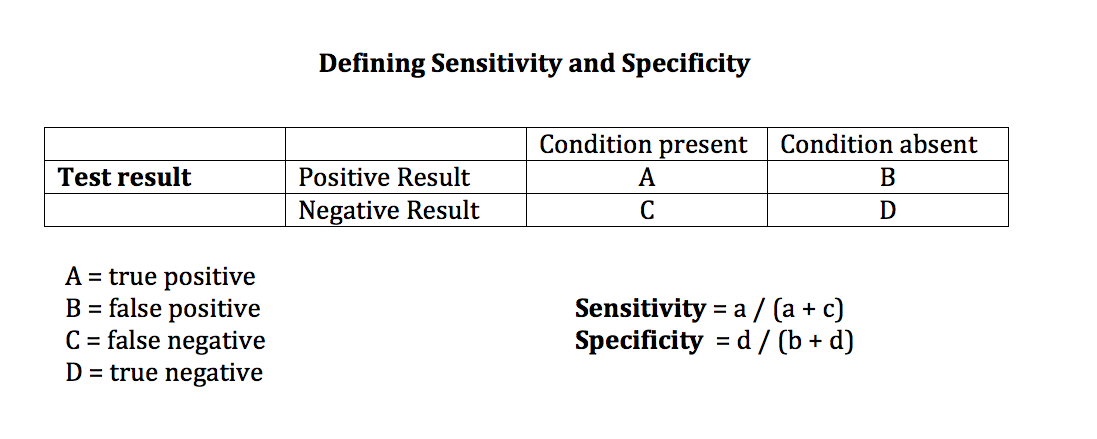

Sensitivity & Specificity

Sensitivity is defined as "the proportion of people with the condition who have a positive test result i.e. true positives."(Hattam & Smeatham, 2010, p. 21-23).

Specificity is defined as "the proportion of people without the condition who have a negative test result i.e true negatives" (Hattam & Smeatham, 2010, p. 21-23).

Terms that you might come across when understanding sensitivity and specificity are:

SnOut: If a test is sensitive then a negative test rules out a condition i.e. a highly sensitive test confidently rules out a condition if that test is not positive.

SpIn: If a test is specific then we can be confident that it is useful in ruling in a condition i.e. a positive result rules in a condition.

But, if the test has high specificity and low sensitivity then a positive test confidently rules in a condition but a negative result doesn't necessarily rule the condition out. This is why we use likelihood ratios to interpret the meaning of these statistics.

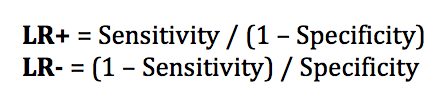

Likelihood ratios

" 'Likelihood ratios', combining sensitivity and specificity, are justified as the best statistics to assess the clinical usefulness of the diagnostic tests they have presented" (Hattam & Smeatham, 2010, p. 10).

A positive likelihood ration LR+ expresses how likely the condition is present with a positive result,

A negative likelihood ratio LR- expresses how likely a condition is absent with a negative result.

In summary, we want high sensitivity and specificity but the likelihood ration further assists in the evaluation and expression of the meaning of the statistics. A LR+ >10 and LR- <0.1 indicates that the outcome of the test has excellent clinical usefulness. A LR+ 1-2 or LR- 0.5-1 indicates poor statistical strength and clinical usefulness. (Hattam & Smeatham, 2010, p. 21-23).

Some principles about clinical tests

When trying to decide what information to take away from the research paper there are some questions you need to be able to answer after reading it. Below is a brief outline of some of these questions. Aim to try expand on these before making your conclusion about the paper.

- Is a journal reputable?

- The answer to this can be found through the ISI (International Scientific Index) which indicates the impact factor of that journal based on the number of times the papers are downloaded and cited.

- The Physical Therapy Journal has an ISI of 3.4 and is ranked #2 against other Physical Therapy Journals.

- What is the internal validity of the study?

- s the research paper testing what it said it would?

- In the methods section you can find out information about how the participants were recruited and allocated to groups. The recruitment often indicates if the study truly represents the population of interest i.e are the results going to be generalizable to the general public and patients seen in a clinical setting?

- What is the clinical applicability of the study?

- Is the research relevant to the clinical setting?

- Does the discussion interpret the results, compare them to previously published studies, and discuss the limitation of the current study design?

- Knowledge generation?

- Does the research generate information that will be utilised?

- The conclusion should outline if the original hypothesis is either accepted or rejected?

- Did the study fill the gaps in research they were looking for?

- What was the major finding and how does this impact your current knowledge?

Hattam and Smeatham (2010, p. 18-20) expand on the questions above by trying answer seven questions when appraising evidence specifically looking at the psychometric properties of clinical tests:

- Is there a clearly defined question?

- Has the diagnostic test being examined been compared to an appropriate reference standard? I.e. has it been compared to a Gold standard, which in musculoskeletal medicine is often surgery or MRI? (Lack of a validated reference standard is often why the tests we use still lack evidential support).

- Has the diagnostic test been evaluated on a spectrum of patients? (Poor sampling often results in over-estimating sensitivity and under-estimating specificity which results in a spectrum bias.

- Has the reference standard been applied to all patients?

- Has the test been defined including the intended use, the technique for executing the test, and a description of a positive and negative outcome?

- Is the test validated in other studies?

- How can you apply this evidence to your own patients?

A clinical example

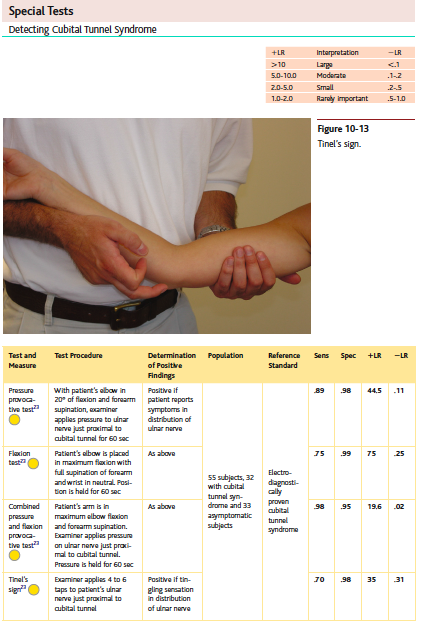

At the elbow, there are four tests described by Cleland et al (2010, p. 454) for the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome: pressure test, flexion test, combined pressure and flexion provocation test and Tinel's sign.

They have presented the test procedure, the outcome of a positive result, what population was tested, the reference standard and the statistics for each test. Everything you need in a simple table format to establish a decision about the best clinical test. In this example the best test is the combined pressure provocation and flexion test which has a LR+ of 19.6 and LR- of 0.02. Meaning that reproduction of the patients symptoms along the distribution of the ulnar border of the forearm with elbow flexion and pressure long the course of the ulnar nerve at the elbow, is highly likely to indicate the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome.

Netter's orthopaedic clinical examination: an evidence-based approach is a great reference text book for understanding the clinical anatomy and clinical tests. They present the statistics very clearly in tables like seen below and list the articles referenced at the end of each chapter. I highly recommend this text as a learning tool when understanding the benefits of each clinical test.

Clinical assessment for cubital tunnel syndrome (Cleland, et al., 2010, p. 454).

Conclusion

In conclusion to this blog, which I hope you have found interesting, the key message that I want to share with you is be skeptical about what you've read until you have confirmed that it brings additional knowledge to the base you already have. In Physiotherapy we are looking for best evidence-based practice. We are not looking to abandoned that which has been confirmed through many years of research. We are not looking to change our approach to physiotherapy. We are looking for ways to grow, enhance and develop our knowledge and skills.

Not all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are high quality studies. The limitations often lie in the ethics of withholding treatment from participants and being unable to completely blind both participants and examiner. The term 'quasi' RCT refers to a experimental design where participant blinding can't be achieved.

Over the years of practice I have learnt just as much from understanding the history and development of our profession as I have from reading the latest releases from the online journals. Aim to be great consumers of research by clarifying the meaning of the study and use the results to amply and expand your current knowledge base.

To stay at the front of the wave of change, we need to rely on balance and a desire to move forward with energy. Don't hold back, you'll fall behind. Don't lean in too hard in case you nose dive.

Sian

References

Cleland, J., Koppenhaver, S., & Su, J. (2010). Netter's orthopaedic clinical examination: an evidence-based approach. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Fritz, J. M., & Wainner, R. S. (2001). Examining diagnostic tests: an evidence-based perspective. Physical Therapy, 81(9), 1546-1564.

Hattam, P., & Smeatham, A. (2010). Special tests in musculoskeletal examination: an evidence-based guide for clinicians. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Malanga, G. A., & Nadler, S. (2006). Musculoskeletal physical examination: an evidence-based approach. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Sackett, D. L. (2000). Evidence‐based medicine. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.