The role of the Scapula in Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: Part 1

The shoulder is a ball and socket synovial joint and nearly everything we do with our hands and arms depends on our shoulders functioning properly. It is estimated that approximately 36% of the general population are affected by shoulder disorders. The shoulder is such a fascinating joint with 180 degrees of freedom, which relies on excellent dynamic movement control in order in order to function well. There are many causes of shoulder pain and the focus for this blog is to focus on these - shoulder impingement syndrome.

During my Masters program I had the great privilege of taking a master class with Lyn Watson, one of Australia's best Shoulder Specialist Physiotherapists. What I learnt most from the master class is that, like all other musculoskeletal injuries, clinical reasoning and a thorough assessment is so crucial.

The following series of blogs will focus on shoulder impingement, the normal function of the scapula, assessment of the shoulder and scapula with a primary focus on shoulder impingement, and to outline potential rehabilitation approach for retaining scapular movements in the presence of scapula dyskinesis. As mentioned previously, Lyn Watson has significantly influenced my clinical reasoning and treatment approach, but there are other wonderful contributors in this field; Dr Ben Kibler, Associate Professor Ann Cools, Jeremy Lewis, Tania Pizzeria and Simon Balster. Let’s take a closer look at my clinical tips that I have learnt from these excellent researchers and physicians.

impingement - is it a diagnosis or symptom?

What does the word actually mean?

How should we use it in the diagnosis of shoulder pain?

Shoulder impingement has been described and researched for many years and some of the original work was described by Neer in the early 1980’s. As our understanding of impingement has expanded we have come to realise that there are many types of shoulder impingement i.e internal and external, and primary and secondary (Ludewig & Braman, 2011).

Internal versus external

This refers to the site of the impingement. If it is located in the subacromial space it is known as external impingement. If it is located within the glenohumeral joint it is known as internal impingement (Cools, Cambier & Witvrouw, 2008).

Courtesy of Google Images http://upl.stack.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Shoulder-Anatomy.png

External impingement occurs when there is direct compression between the rotator cuff tendons and/or long head of bicep tendons, between the humeral head and the undersurface of the acromion, coracoacromial ligament, or the ACJ (Neer, 1983).

Internal impingement occurs when there is compression of the supraspinatus tendon and/or infraspinatus tendon between the humeral head and posterosuperior glenoid rim. This usually occurs at 90 degrees abduction and external rotation. (Watch, 1992). But there may also be impingement of the subscapularis tendon, long head of biceps tendon or parts of the glenoid labrum.

So keep in mind that simply saying "impingement" as a diagnostic label does not tell you:

- What structure is involved.

- Where in the shoulder the impingement is occurring.

- Or, what range or position the arm is in when the impingement occurs.

Primary versus secondary

This refers to the cause of impingement.

Primary impingement is a structural narrowing of the subacromial space due to acromioclavicular athropathy, a hooked acromion, or pathology within the tissues in the subacromial space (LHB tendon, supraspinatus tendon, subacromial bursa).

This is important to bear in mind because many people jump to the assumption that if structures are impinged, surgery is required to ‘make more room'. This may not be the case and if the pathology is within the tendon itself, surgery will not address the primary problem (Lewis, 2011).

Secondary impingement can occur from:

- Glenohumeral joint instability, which can lead to excessive humeral head translation and/or poor position of the humerus in relation to the scapula.

- Scapula dyskinesis

- GIRD (glenohumeral internal rotation deficit) There is a loss of glenohumeral internal rotation and increase in external rotation, often the posterior cuff & capsule become tight and there is anterior translation of the humeral head resulting in secondary impingement.

Secondary impingement can affect the rotator cuff tendons or LHB, and can be both internal and external (Burkhart, Morgan & Kibler 2003; Cools, Cambier & Witvrouw, 2008; Ludewig & Braman, 2011).

As you can see the word impingement is more of a descriptive symptom of shoulder pain that a clear cut diagnostic label and hence why it is called shoulder impingement syndrome (with an emphasis on the word syndrome)(Kibler, et al., 2014). Hopefully this first section shows you why the diagnosis of shoulder impingement is controversial. It can leave the clinician and patient without knowledge of what structure is at fault, where it is occurring and why.

As a younger clinician I always felt daunted by these words because I gave me no direction for assessment and treatment. What I have learnt now is that the word itself should not change the assessment you perform of a painful shoulder, it merely guides your clinical reasoning.

Assessment of the shoulder complex

When assessing the knee there are only two movements, flexion and extension. Shoulders are even more complex having so many ranges of movement. I clearly remember always struggling to think about all the possible diagnoses and being overwhelmed by having to assess flexion, extension, external and internal rotation, abduction, adduction, horizontal flexion and extension and then looking at special tests….. phew it was often just way too much to stomach.

The key to improving your assessment of shoulders is to have a routine in your assessment technique. A framework you can fall back on or vary from depending what you're looking for. For example, always assess the injured then the non-injured side or always assess movements in the same order. That way when you are trying to remember what each test revealed, you'll have a sequence in your mind to remember from.

Cools et al (2008) published a fantastic paper outlining an assessment algorithm to assist clinicians in their screening of shoulder patients with suspected impingement and clinical diagnosis. This algorithm is a great place to start when you're developing skills in shoulder assessment.

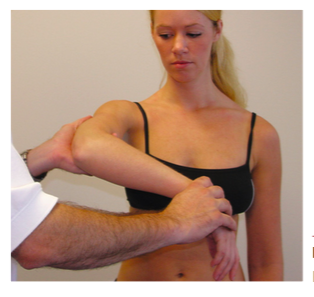

You would have learnt about all of these tests during your training but there are two that are particularly useful to revisit and these aren't the typical shoulder impingement tests. Nope, you can go look them up in a book or online. Netter's Orthopaedic Clinical Examination is a fantastic text for discussing the performance and clinical validity of musculoskeletal clinical tests. Just to jolt your memory though, the images below represent the Hawkin's Kennedy, Neer, and Jobe test for shoulder impingement described in the algorithm above (Cleland, 2005).

Until I studied this algorithm however, the scapula assistance test & scapula retraction test were not a routine part of my assessment.

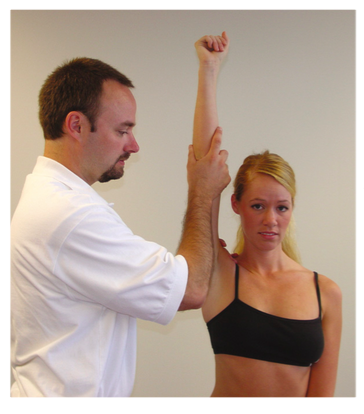

(Cools, Cambier & Witvrouw 2008, p. 631)

Scapula assistance test assesses the impact of correcting scapula position on shoulder pain and impingement symptoms during active shoulder elevation. So the clinician assists the scapula into upward rotation while the patient elevates their arm and observes if there is a change in pain.

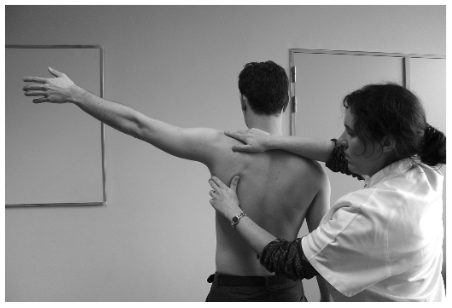

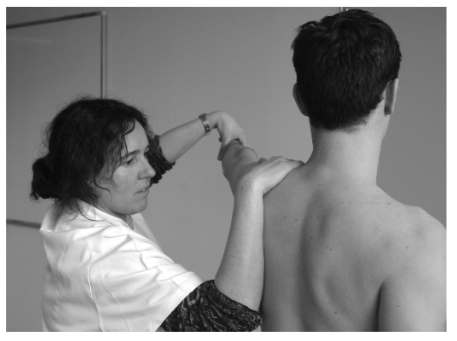

(Cools, Cambier & Witvrouw 2008, p. 631)

Scapula retraction test assesses the impact of maintaining scapula position during loading and assessing the impact on pain. For the scapula resistance test the therapist resists the scapula into retraction while assessment pain in the resisted elevation in an abducted and internally rotated position.

Putting it all together

I love this article by Cools, Cambrier & Witvrouw (2008) because it clearly goes through each step of the algorithm discussing what a positive test result is. It also discusses how to complete each test and then puts each diagnostic category into perspective. A recommended read for sure.

When assessing a shoulder I always try to focus on the following:

- Carefully observing the functional aggravating position.

- Reproducing shoulder symptoms and then trying to change them with scapula positioning, muscle activation exercises or manual therapy.

- If there is a reduction in pain it indicates a ‘green light’ to go ahead and treat with conservative rehabilitation.

- If there is no green light - you will need to reconsider your diagnosis, consider a referral for medical imaging and/or referral to a specialist for further investigation.

From the reading that I have done on this topic there seems to be a large conversation about the role of the scapula and a growing amount of research linking scapula dyskinesis to a variety of shoulder conditions (Kibler, et al., 2014). I would recommend reading the Scapula Summit from 2013, which provides an overview about what we do and don't know from current research.

Before we discuss the rehabilitation principles for shoulder impingement syndrome, we first need to take a slight detour and revisit the scapula. One of the main recommendations from the Scapula Summit about shoulder impingement was that scapular assessment needs to be incorporated into our assessments.

Before we continue to the next blog I'd ask you try answer these few questions.

- What movements occur at the scapula?

- Describe normal scapulohumeral rhythm.

- What is it’s resting position of the scapula on the thorax and how does this change during elevation?

- Name the muscles attaching to the scapula and what force couples occur during each movement.

- How do you individually assess each of these muscles?

Ok, let’s continue and take a closer look at scapula dyskinesis with particular focus on how it relates to shoulder impingement syndrome. Don’t worry - if you couldn’t be bothered answering those questions, I’ll go over them anyway :)

Sian

References:

Braman, J. P., Zhao, K. D., Lawrence, R. L., Harrison, A. K., & Ludewig, P. M. (2014). Shoulder impingement revisited: evolution of diagnostic understanding in orthopedic surgery and physical therapy. Medical & biological engineering & computing, 52(3), 211-219.

Cools, A. M., Cambier, D., & Witvrouw, E. E. (2008). Screening the athlete’s shoulder for impingement symptoms: a clinical reasoning algorithm for early detection of shoulder pathology. British journal of sports medicine, 42(8), 628-635.

Cools, A. M., Declercq, G., Cagnie, B., Cambier, D., & Witvrouw, E. (2008). Internal impingement in the tennis player: rehabilitation guidelines. British journal of sports medicine, 42(3), 165-171.

Kibler, W. B., & McMullen, J. (2003). Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons,11(2), 142-151.

Kibler, W. B., Ludewig, P. M., McClure, P. W., Michener, L. A., Bak, K., Sciascia, A. D., ... & Cote, M. (2013). Clinical implications of scapular dyskinesis in shoulder injury: the 2013 consensus statement from the ‘scapular summit’. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2013.

Kibler, W. B., Sciascia, A. D., Bak, K., Ebaugh, D., Ludewig, P., Kuhn, J., ... & Cote, M. (2013). Introduction to the second international conference on scapular dyskinesis in shoulder injury—the ‘Scapular summit’report of 2013.British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2013.

Ludewig, P. M., & Braman, J. P. (2011). Shoulder impingement: biomechanical considerations in rehabilitation. Manual therapy, 16(1), 33-39.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome part 2: conservative management of thoracic outlet. Manual therapy, 15(4), 305-314.