Neurodynamic treatments for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

"The main goal of treatment is to relieve the compression and ... reduce the progression of symptoms" (Kaczynski & Fligelstone., 2013. p.8).

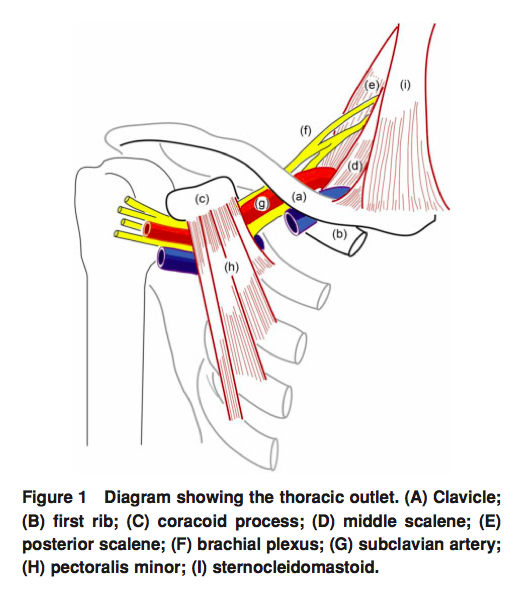

(Hooper et al, 2010a, p. 75)

As previously stated, Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a difficult condition to diagnose and successful treatment will depend heavily on accurately identifying the sub-type of TOS that the patient is presenting with.

To begin with, it is important to identify the patients who will require surgical management (the minority).

Surgical treatment.

Kaczynski & Fligelstone (2013) conducted a trial to evaluate the surgical and functional outcomes following surgical decompression, using the Disability of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (DASH). All surgeries were performed using the supraclavicular approach and involved either excision of the cervical or first rib, and/or scalenectomy.

The outcome from this trial support and strengthen the findings of previous literature:

- For arterial TOS, which often presents with a clear structural abnormality, success rates are as high as 90% post-operatively and many patients will remain asymptomatic.

- For true neurological TOS, success rates can be as high as 93% initially, however many will drop to 64-71% and require follow up physiotherapy.

- There is a high rate of post operative complications, which may include damage to the phrenic or long thoracic nerve, Horner's syndrome, damage to the supraclavicular nerves, intercostal brachial injuries, pneumothorax and haemothorax (Mackinnon & Novak, 2002. p.1124).

- It is becoming more accepted that patients undertake a trial of conservative physiotherapy treatment for 4-6 weeks prior to considering surgical decompression (Kaczynski & Fligelstone, 2013; Watson et al., 2010).

Conservative treatment for neurogenic TOS

Throughout the literature many authors/studies recommend postural correction, strengthening of muscles, and lengthening of muscles but, there isn't consensus as to which muscles should be specifically targeted (Hooper, et al., 2010; Vanti, et al., 2010; Watson, el al., 2010). This highlights the importance of individualised assessment to identify patient-specific goals for treatment.

I attended a lecture hosted by the MPA and presented by Simon Balster (Specialist Shoulder Physiotherapist) on the diagnosis and treatment of TOS. His lecture really reinforced the message that every condition requires a thorough musculoskeletal examination and systematic treatment based on the assessment findings. A previous blog explores the assessment and differential diagnosis for TOS. The treatments suggested below are summarised from my broader reading on this topic.

The main concepts/treatment approaches for conservative management include:

- Postural correction.

- Retraining of scapular stability in upward rotation (Watson et al., 2010).

- Mobilisation of the hypomobile cervical spine, thoracic spine and first rib.

- Addressing opening and closing dysfunction and altered neural mechanosensitivity (Shacklock, 2005; Vanti et al., 2007; Wehbe, 2004).

- Deep cervical neck flexor muscle control and strength.

- Lengthening/soft tissue treatments for sternocleidomastoid, anterior and middle scalenes, and pectoralis minor i.e. muscles that compress the 'container' further.

- Restoration of normal breathing patterns.

I now want to explore treatments I have found to have the greatest impact in the clinical setting. The first is a neurodynamic approach to addressed pathophysiology and pathomechanics of the neural structures, and the second is a scapular-focussed approach to improving the thoracic outlet space.

Clinical neurodynamics

Many of the studies on neurodynamic exercises for the treatment of TOS use 'standard' assessments and active treatments based on standard testing using the median or ulna nerve sequences. After attending Michael Shacklock's course on clinical neurodynamics I have learnt more about the varied levels of assessment and treatment for TOS.

Step 1: assess to an appropriate and safe level.

This may mean that a standard median or ulna nerve sequence is too strong/provocative and a level 1 assessment is required. Or alternatively, the patient's symptoms have low severity and are non-irritable and may require a more sensitised level 3 assessment. These are all outlined thoroughly in his text book.

Step 2: decide if the problem is due to pathophysiology or pathomechanics.

There are two main models for neurodynamic treatments:

- What is good for the nerve is good for the muscle, and therefore joint/soft tissue treatment techniques will be helpful to both.

- What is good for the nerve isn't good for the muscle and different treatments are required. In the case of TOS we often see this pattern with treatment options. An example of this is depression of the first rib, which increases the costoclavicular space by moving the rib away from the clavicle and off loads the neural tissues, but, places the scalene muscles on further stretch.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology refers to damage to the nervous tissue through inflammation or hypoxia which often leads to chemical changes within the tissue such as mechanosensitivity, lowered threshold for activation and increased response to input. Pathophysiology can occur as a result of the mechanical dysfunction i.e neural tissue inflammation due to compression from an intervertebral disc herniation, or neural tissue changes which occur with disease processes such as diabetes.

Remember that mechanosensitivity does not solely refer to sensitivity to movement or palpation. Mechanosensitivity can occur in sympathetic, motor, proprioceptive and nociceptive nerve fibres.

Pathomechanics

- Is there an interface dysfunction that needs addressing i.e. open or closing dysfunction?

- Is the problem due to excessive or reduced movement at the interface?

- Is there a neural dysfunction that needs addressing i.e tension or sliding dysfunction?

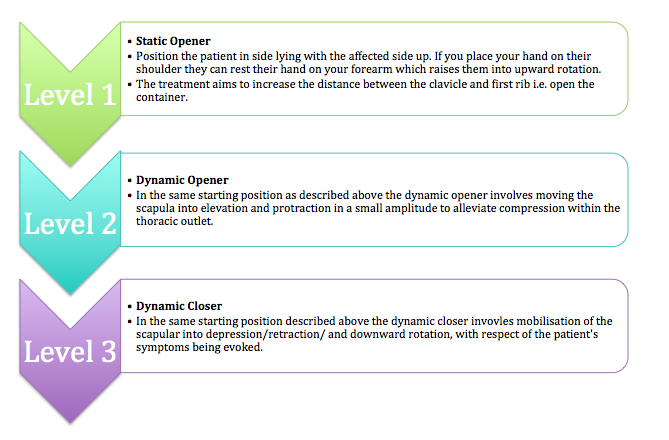

Treatment of interface dysfunctions using a neurodynamic approach.

Reduced closing dysfunction is defined by Shacklock as a problem "when the mechanical interface lacks appropriate movement in the closing direction" (2005, p. 53). Where as, excessive closing dysfunction describes "when the interfacing movement complex demonstrates more movement than normal, or is undesirable, in the closing direction" (2005, p. 53).

Opening dysfunctions can also be described as reduced or excessive and refer to the "opening mechanism of the movement complex that is located adjacent to the nervous system" (2005, p. 54).

Adapted from, Shacklock M, Clinical Neurodynamics, Elsevier, Oxford, 2005.

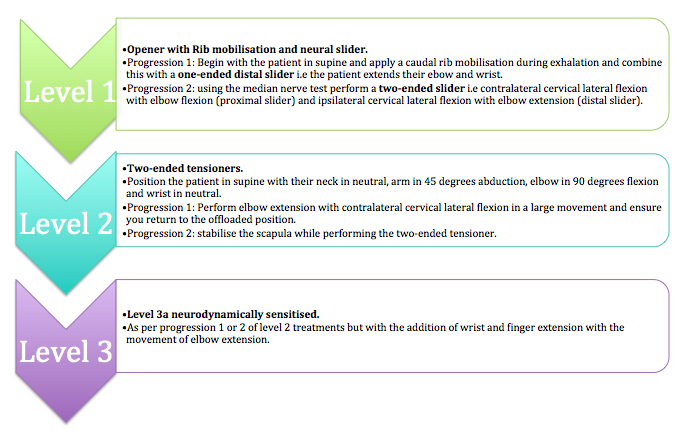

Treatment of neural dysfunction using a neurodynamic approach.

Adapted from, Shacklock M, Clinical Neurodynamics, Elsevier, Oxford, 2005.

Summary and clinical tips

- Breathing should be coordinated with the sequence of treatment, as inhalation raises the first rib beneath the clavicle and exhalation moves it away.

- Depression of the first rib increases the costoclavicular space only if the scapula doesn't move.

- When palpating the first rib there is no movement at the elbow. If you are on the scapula there will be a 1:1 movement at the elbow. Check you're on the right spot!

- When using neurodynamic tests a positive result does not indicate the cause of the pathodynamics and clinical reasoning/further assessment is required to understand if pathomechanics or pathophysiology is involved and the cause/mechanism of the symptoms.

- The two images above present treatment techniques described in Shacklock M, Clinical Neurodynamics, Elsevier, Oxford, 2005. These treatments are not the treatments which are described in the research for TOS and therefore it is difficult to comment on the supporting evidence. The reason I have presented them rather than the treatments from the trials is that they accommodate for patient severity and irritability and allow us as clinicians to vary our assessment/treatment based on a deeper understanding of the driving mechanisms for the pathoneurodynamics.

The following blog will explore scapular retraining for thoracic outlet syndrome.

Sian

References

Hooper, T. L., Denton, J., McGalliard, M. K., Brismée, J.-M., & Sizer Jr, P. S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 1: anatomy, and clinical examination/diagnosis. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 18(2), 74.

Hooper, T. L., Denton, J., McGalliard, M. K., Brismee, J. M., & Sizer, P. S., Jr. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome: a controversial clinical condition. Part 2: non-surgical and surgical management. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 18(3), 132-138.

Kaczynski, J., & Fligelstone, L. (2013). Surgical and Functional Outcomes After Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Decompression via Supraclavicular Approach: A 10-Year Single Centre Experience. Journal of Current Surgery, 3(1), 7-12.

Lindgren, K.-A. (1997). Conservative treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome: a 2-year follow-up. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 78(4), 373-378.

Mackinnon, S. E., & Novak, C. B. (2002). Thoracic outlet syndrome. Current Problems in Surgery, 39(11), 1070-1145.

Peet, R. M., Henriksen, J. D., Anderson, T., & Martin, G. M. (1956). Thoracic-outlet syndrome: evaluation of a therapeutic exercise program. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the staff meetings. Mayo Clinic.

Roos, D. B. (1990). The thoracic outlet syndrome is underrated. Archives of neurology, 47(3), 327.

Sanders, R. J. (2013). Anatomy of the Thoracic Outlet and Related Structures Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (pp. 17-24): Springer.

Sanders, R. J., Hammond, S. L., & Rao, N. M. (2007). Diagnosis of thoracic outlet syndrome. Journal of vascular surgery, 46(3), 601-604.

Shacklock, M. O. (2005). Clinical neurodynamics: a new system of musculoskeletal treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2009). Thoracic outlet syndrome part 1: Clinical manifestations, differentiation and treatment pathways. Manual therapy, 14(6), 586-595.

Watson, L. A., Pizzari, T., & Balster, S. (2010). Thoracic outlet syndrome Part 2: Conservative management of thoracic outlet. Manual therapy, 15(4), 305-314.