Clinical presentation of neuropathic pain.

"Peripheral neuropathic pain is the term used to describe situations where nerve roots or peripheral nerve trunks have been injured by the mechanical and/ or chemical stimuli that exceeded the physical capabilities of the nervous system" (Nee & Butler, 2006., p.36).

This article by Nee & Butler (2006) outlines the clinical presentation of neuropathic pain and differentiates between nerve trunk pain and dysesthetic pain. The key points I took from reading this were:

Peripheral neuropathic pain may present as either positive or negative symptoms.

"Positive symptoms reflect an abnormal level of excitability in the nervous system and include pain, paraesthesia, dysesthesia, and spasm. Negative symptoms indicate reduced impulse conduction in the neural tissues and include hypoesthesia or anesthesia and weakness" (Nee & Butler, 2006., p.36-37).

Peripheral neuropathic pain may present with nerve trunk pain or dysesthetic pain.

Nerve trunk pain can be a result of mechanically or chemically sensitised nociceptors. There are different presentations of the exaggerated response to mechanical, chemical or thermal stimuli which include hyperalgesia, allodynia, hyperpathia and windup.

Nerve trunk pain may also be worse with increased personal life stress, reflecting the role of the neuroimmune system, and the impact inflammatory chemicals can have on nervous tissue centrally through the blood-brain barrier.

Dysesthesic pain refers to the unusual symptoms patients often report accompanying their pain such as "burning, tingling, electric, searing, drawing, or crawling" (Nee & Butler, 2006. p.37). It is thought to be an output from hyperexcitability of damaged or regenerative nervous tissue.

The distribution of pain may follow a dermatomal pattern or it may be variable.

"Sensory and motor fibres display intradural connections between adjacent spinal cord segments, which means that neural injury near the intervertebral foramen can affect nerve fibres associated with more than one spinal cord level. Central nervous system neurons become sensitized after peripheral nerve injury and expand their receptor fields, a process that can also explain why peripheral neuropathic symptoms may spread beyond typical dermatomal and cutaneous field boundaries" (Nee & Butler, 2006., p37).

Physical examination findings need to reflect mechanosensitivity in the neural tissues to diagnose peripheral neuropathic pain.

- Use neurodynamic tests for the upper and lower limb to understand both a normal and positive response:

- The test must reproduce the patients symptoms.

- Sensitisation is achieved by moving a segment which is away from the site of symptoms.

- Document asymmetry in response, range, resistance, and the limiting factor.

- Resistance is not a reflection of the elastic nature of tissues but an indication of protective muscular activity.

- A positive response to neurodynamic testing does not specify the site of dysfunction.

- Understanding and exploring the affect of sequencing during neurodynamic testing.

- For further description on the procedure of neurodynamic testing I would recommend Shacklock's text (2005) as it has a great outline of test procedure, positive and normal response and sensitising movements.

- Incorporate nerve trunk palpation and peripheral nerve palpation into the examination.

- Assess active and passive movement impairments.

- Many peripheral conditions have specific pain provocations tests which can be included in the assessment.

- The goal of the physical examination is to match subjective and physical findings and to find a musculoskeletal cause of the peripheral neuropathic pain.

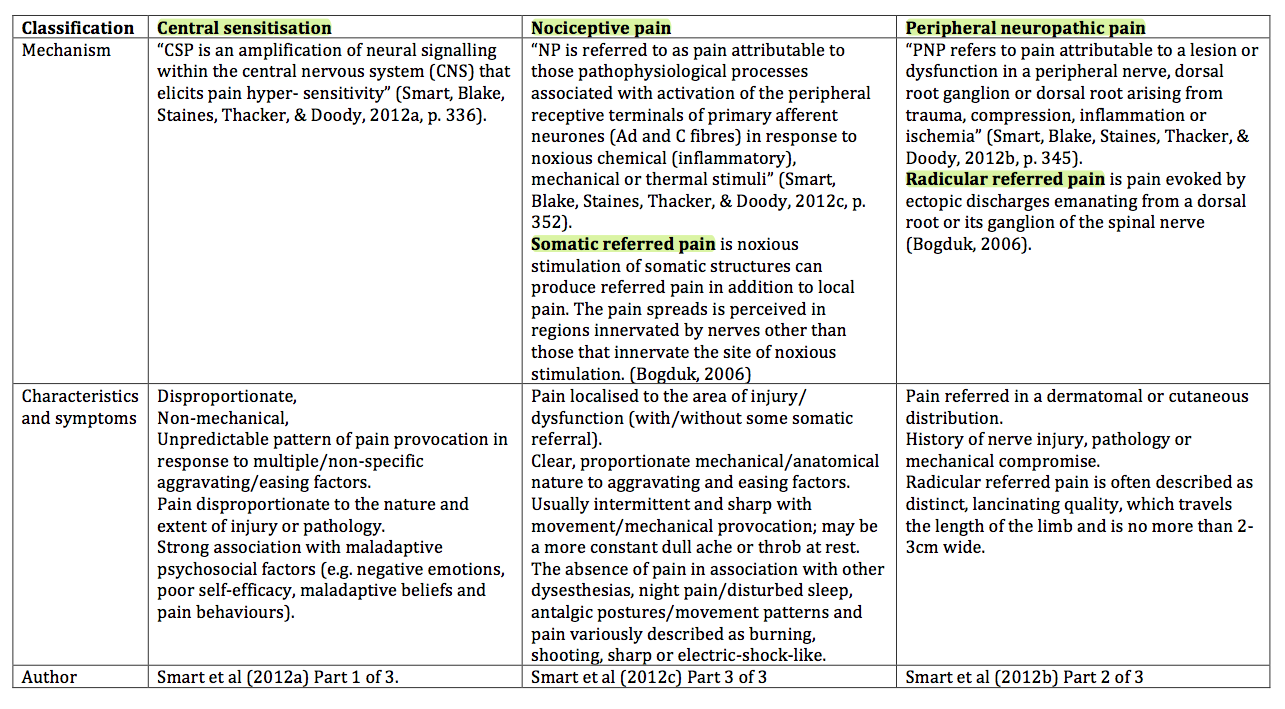

Peripheral neuropathic pain should also be differentiated from central sensitisation and nociceptive pain mechanisms. A mechanism-based classification of pain has been proposed by a series of Delphi studies regarding the classification of pain in lower back pain patients. Below is a summary of the features of each pain category to help distinguish pain mechanisms.

Assessing, diagnosing and managing neuropathic pain is something that continues to push the boundaries of my clinical reasoning and challenge my management skills.

For more information on the clinical presentation and proposed mechanisms for neuropathic pain and the presentation of Double Crush Syndrome, refer to Nee & Butler (2006) and Schmid & Coppieters (2011).

Sian

References

Bogduk, N., & McGruik, B. (2006). Management of acute and chronic neck pain. An Evidence-based approach. United Kingdom: Elsevier.

Nee, R., & Butler, D. (2006). Management of peripheral neuropathic pain: Integrating neurobiology, neurodynamics, and clinical evidence. Physical therapy in sport, 7(1), 36-49.

Schmid, A. B., Brunner, F., Luomajoki, H., Held, U., Bachmann, L. M., Kunzer, S., et al. (2009). Reliability of clinical tests to evaluate nerve function and mechanosensitivity of the upper limb peripheral nervous system. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 10, 11.

Shacklock, M. (2005). Clinical Neurodynamics: A new system of musculoskeletal treatment. Edinburgh: Elsevier

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., & Doody, C. (2010). Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain. A Delphi survey of expert clinicians. Manual therapy, 15(1), 80-87.

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., Thacker, M., & Doody, C. (2012a). Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 1 of 3: Symptoms and signs of central sensitisation in patients with low back (±leg) pain. Manual therapy, 17(4), 336-344.

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., Thacker, M., & Doody, C. (2012b). Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 2 of 3: Symptoms and signs of peripheral neuropathic pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain. Manual therapy, 17(4), 345-351.

Smart, K. M., Blake, C., Staines, A., Thacker, M., & Doody, C. (2012c). Mechanisms-based classifications of musculoskeletal pain: Part 3 of 3: Symptoms and signs of nociceptive pain in patients with low back (±leg) pain. Manual therapy, 17(4), 352-357.